Lent is over, Pascha has come and gone, and Christ is risen. This year, as the resurrection approached, my mind regularly returned to the parable that inaugurates the lenten season: the parable of the Publican and the Pharisee. That is probably because, as usual, I did not live up to the good intentions I set at the start, to keep the fast to the letter, to deepen my daily prayer discipline, to humble myself properly. Certainly this year, I failed miserably. But also, if you practice the Jesus Prayer, even half-heartedly as I do, then this particular parable will never be far from your mind. After all, the Jesus Prayer is based on the Publican’s anguished cry of repentance: ‘Lord, have mercy on me, sinner that I am!’

Here is the passage in full, from Luke chapter 18:

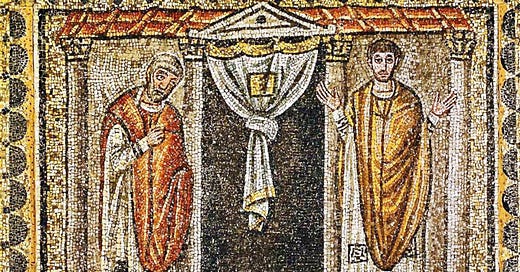

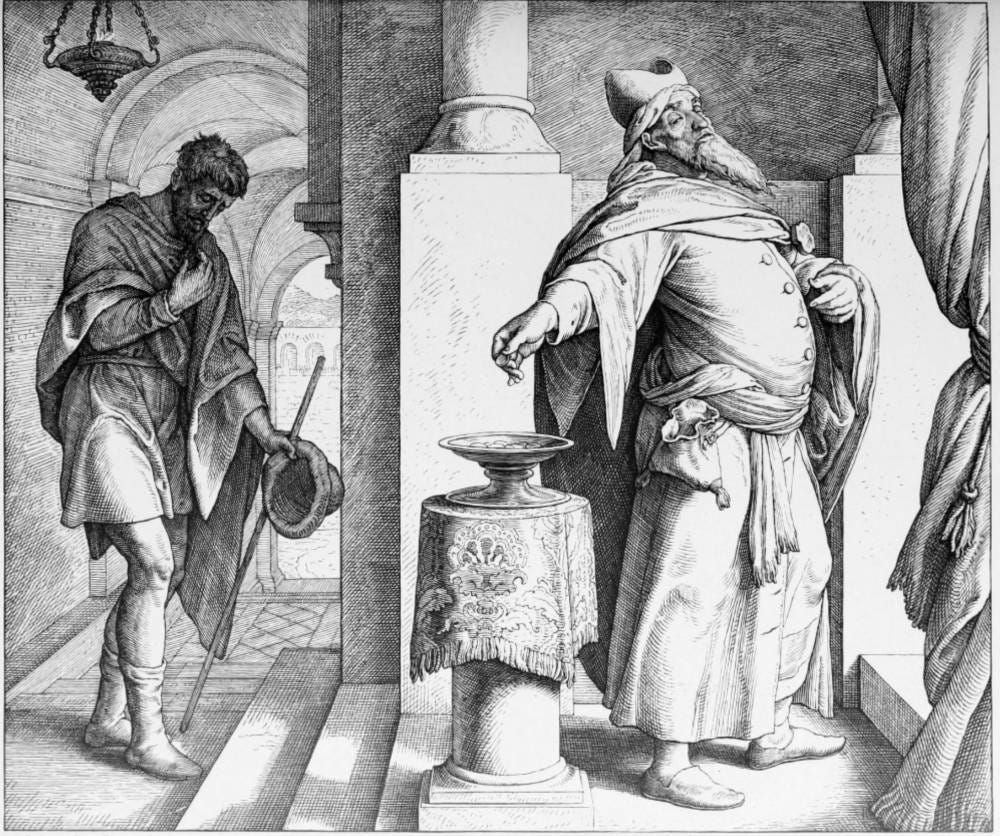

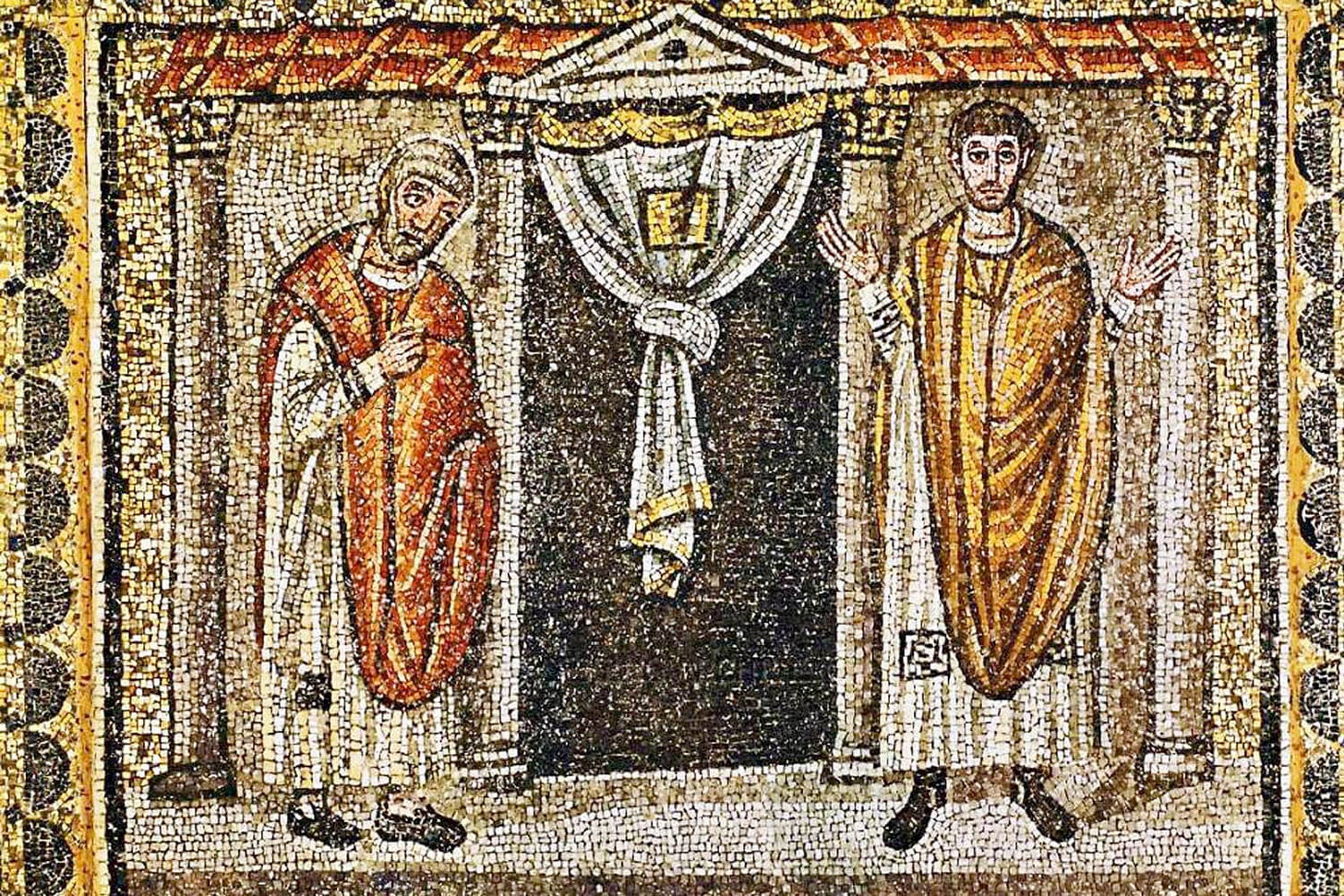

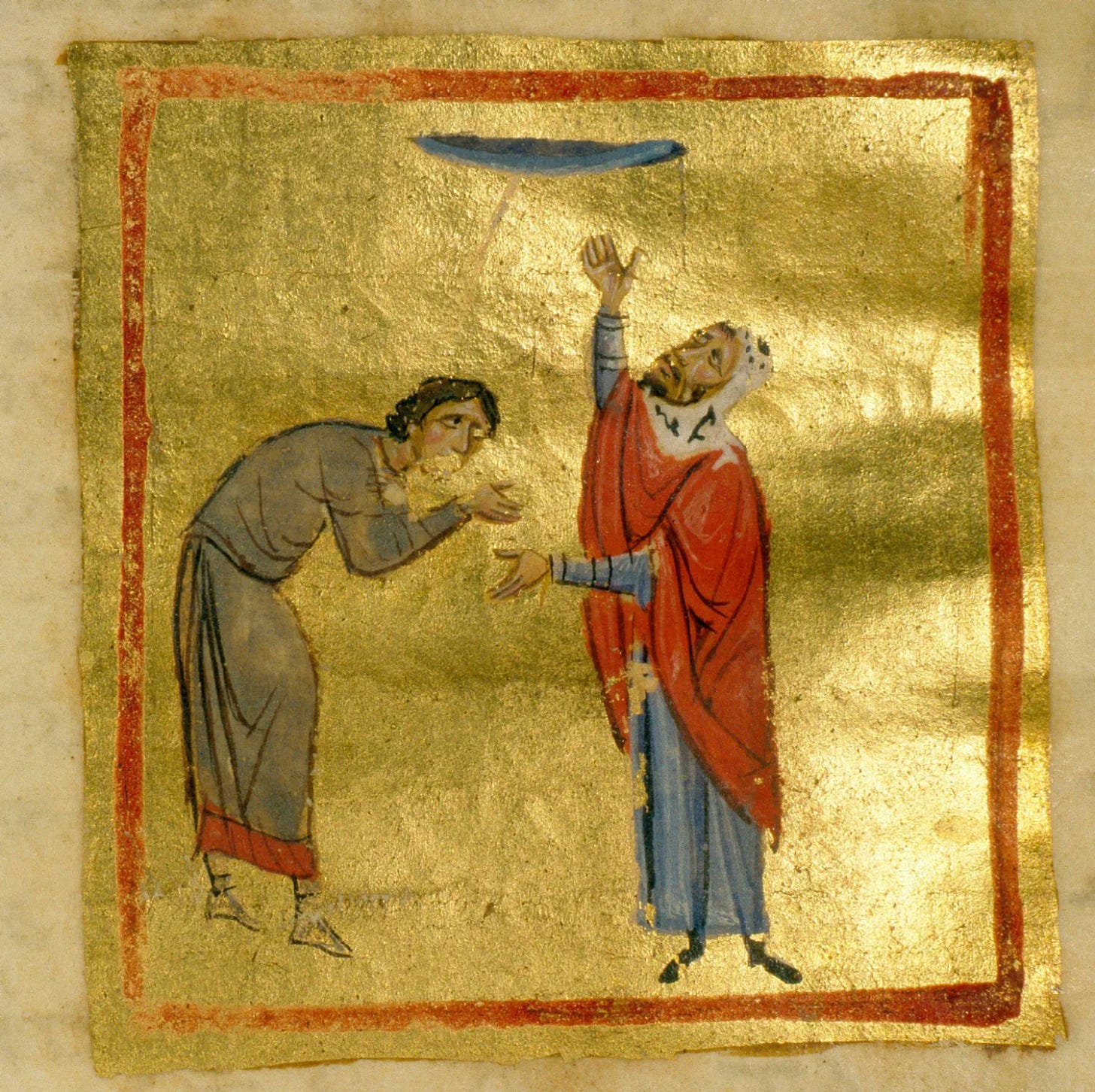

Then he told this parable to those who trusted in themselves that they are righteous while despising the rest. ‘Two men went up to the temple to pray. One was a Pharisee and the other a Publican—a tax collector. The Pharisee stood praying to himself like this: “I thank you, O God, that I am not like the rest of mankind: greedy, unrighteous, adulterous, or even like this tax collector. I fast twice a week. I give away ten percent of everything I earn.” But the Publican, standing at a distance, would not even lift up his eyes to heaven, but was beating his breast, saying, “God be merciful to me, the sinner!” I tell you that this man went home justified, but not the other. For everyone exalting himself will be humbled, but he who humbles himself will be exalted.’

From the first sentence, self-righteousness is established as the theme of the parable: ‘Then he told this parable to those who trusted in themselves that they are righteous while despising the rest.’ The very definition of self-righteousness. And notice, self-righteousness has two dimensions. First, instead of trusting in the promises of God, you trust in yourself that you are righteous. Second, instead of loving everyone, including even your enemies, you hold them in contempt. Self-righteousness and contempt for others are two dimensions of a single sickness. As St Theophylact of Ochrid wrote in the 11th century, in his commentary on the parable:

When a man credits his accomplishments to himself rather than to God, this amounts to nothing less than denying God and opposing him. Therefore, like one enemy opposing another, the Lord stands against this passion which sets itself against him—and through this parable, he promises to heal it. He addresses the parable to those who put their trust in themselves, who fail to attribute everything to God, and who, as a result, look down on others. He shows that when righteousness—which is marvellous in every other respect and brings a man near to God—takes pride as its companion, it casts that man into the lowest depths and turns what was godlike just moments before into something demonic.

Righteousness becomes self-righteousness when mixed with pride. Something divine becomes something demonic.

So, according to one interpretation, God has granted us a degree of righteousness, and to keep it from curdling into self-righteousness our prayer must centre not on the merely human, but on the divine side of the divine-demonic polarity that St Theophylact describes. Avarice and ambition, the vices of the Publican, are merely human vices. Each of us, being human, can easily succumb to them. Indeed, to some extent, all of us regularly do. The wonder is, human vice is eminently redeemable by divine virtue—of which there is none greater than humility. Meanwhile, fasting and tithing, the virtues of the Pharisee, are merely human virtues. They lie well within the reach of any able-bodied person. But here is the bitter truth: though admirable, human virtues count as nothing when mixed with demonic vice—especially the worst of all, pride.

But God is a refining fire. He wants to purify the righteousness in you. That is what the parable is for. God uses the parable to cause an almost alchemical reaction. He separates out the pride that has polluted your righteousness, so that he can restore you to perfect health through humble repentance.

And yet, many people believe the parable teaches, not that pride pollutes righteousness, but that righteousness inevitably leads to pride. Because he was so focused on the categories of virtue and vice, the Pharisee could not help but become supercilious and judgemental. To avoid self-righteousness, such thinking concludes, it is best to avoid righteousness altogether. Instead of acquiring virtue, you should simply focus on being ‘non-judgemental.’ Or rather, for such people, being non-judgemental is the very definition of virtue.

That way of thinking, by exaggerating a partial truth out of all proportion, obscures the full truth rather than reveals it. Christ does not condemn righteousness. Elsewhere he explicitly states that our righteousness should exceed the righteousness of the Pharisees. And St Theophylact says that the Pharisee’s virtues are ‘marvellous’ in every way. Meaning that, on the face of it, the Pharisee is not lying. He has fasted, tithed, and avoided major sins. He probably did everything he should, and nothing he should not. Is this something to criticize? Are we not also supposed to fast twice a week and give alms? To do what is right and avoid what is wrong? After all, it is not as if Christ is asking us to emulate the Publican’s behaviour in general. He knew what tax collectors got up to. In the ancient world, they were engaged in reprehensible behaviour: theft, extortion, collaboration with tyranny. When St Matthew leaves his tax booth to follow the Lord, it is not a sign of the righteousness of tax collecting. Rather, it shows the Gospel’s power, that it can convince even a tax collector to give up something as wicked as tax collecting. That is why elsewhere Christ says that the Church, when casting out the stubbornly unrepentant, should consider them to be ‘like Gentiles or tax collectors’.

What Christ praises is not the Publican’s sin. Christ condemns all sin. What earns Christ’s commendation is the fact that the Publican went up to the temple to repent of his sin. As a reward for his humility, he receives forgiveness and leaves justified. Which is to say, he leaves made righteous. Having accepted his repentance, the Holy Spirit grants him the power to make good on that repentance by living a life free from sin.

So no, the Lord does not praise sin or condemn righteousness. He praises humility and condemns self-righteousness.

You will say this is all pretty self-evident. Sure, the parable is about genuine righteousness versus self-righteousness, humility versus pride. Everyone knows that. However, what is less obvious is how the parable, from that very first sentence, explicitly defines its intended audience: ‘Then he told this parable to those who trusted in themselves that they are righteous while despising the rest.’ A specific category of person is being addressed: the self-righteous. They are the ones Christ wants to illuminate; he wants to heal them of their special sickness, self-righteousness.

What this reveals is often overlooked: that unless you recognize this sickness in yourself, the parable has nothing to offer you.

We usually do not read the parable that way. Instead, we treat it as a simple morality tale. One person is held up as someone we should not emulate, the Pharisee; another as someone we should, the Publican. And so, when the Pharisee walks on stage, we boo and hiss, as if at a pantomime villain. We rush—piously, we suppose—to disidentify with him. Anything but be like a Pharisee! It is only when the spotlight swerves to the Publican that our conscience suddenly stirs. His penitence moves us to think upon our many sins, perhaps especially sins of the flesh, and our spirit cries out with his: ‘Lord, have mercy on me, sinner that I am!’

All of Christ’s parables that contrast two characters or images are usually read moralistically in that way, pitting a good exemplar against a bad one. And this reading is not entirely wrong. But it is superficial. Such parables are better understood, I believe, as illuminating two aspects or potentialities within a single person. Each of us harbours both a Prodigal Son and his older brother; a wise virgin and a foolish; a sheep and a goat. We are both men sleeping in one bed, both women grinding at the mill, and both houses, the one built on sand and the one built on rock. We are the son who says he will go but does not, and the one who refuses but obeys in the end. Beyond even the parables, there is a Good Thief and a Bad Thief in each of us—with Christ crucified between them. And we carry an inner Pharisee and an inner Publican as well. In all of these pairings, the two figures represent two spiritual or psychological movements within the soul—two postures, two possibilities, two poles of a single dynamic. Though expressed in dual form, the referent is ultimately one: the individual human being.

Reading the parable moralistically puts the cart before the horse, and misses the entire point. Christ does not want us simply to identify with the good guy and disidentify with the bad guy. He is not only addressing our sins of the flesh or inviting us merely to confess our favourite list of moral failings. He is speaking to something deeper. His goal is to cure our self-righteousness—indeed our pride, the root of all sin and immorality. And so he is not saying, don’t be the Pharisee. Like a good doctor, he has diagnosed your illness and is telling you straight, you already are the Pharisee. This demands a far more radical repentance: to become a truly repentant Publican, you must acknowledge your own inner self-righteous Pharisee. Struggle as you might, you cannot escape it. The very moment you disidentify with the Pharisee, you become him. You are, in effect, echoing his prayer: ‘I thank you, O God, that I am not like the Pharisee!’ No, you are like the Pharisee. We all are. And unless you identify with the Pharisee first, as Christ insists, the parable’s healing power, embodied in the Publican’s cry of repentance, cannot take effect in you.

Identifying with the Pharisee is painful. But we must endure that pain if we are to receive the healing on offer. And for this, it helps to understand the illness. I have called it self-righteousness, or pride, and the parable links it to impure prayer. But what is pride exactly?

First, pride is different from vainglory. They are often confused. And to be sure, they are interrelated, and they both pollute prayer. But pride and vainglory are distinct passions with different causes and different effects.

Vainglory is the passion of taking pleasure in praise, attention, and esteem. It is what moves you to strive for success and admiration. If there is any worldly ambition in you, vainglory underlies it. Yet, like all the passions, vainglory is not itself a pattern of behaviour, but a disordered impulse anchored deep within your heart. As such, it is mostly hidden from view—often even from yourself. It is what causes you, inwardly, to overestimate your own intelligence or competence. Bewitched by self-conceit, only then do you manifest vainglory outwardly, maybe by expounding confidently on matters you know nothing about (as I am doing here). More insidiously, vainglory gives rise—again, inwardly—to the feeling of being inherently interesting or important. Once mesmerized by self-regard, you become compulsively attention-seeking, calibrating every move you make, even unconsciously, to draw notice to yourself; positive or negative, it does not much matter, so long as it is attention. At its worst, vainglory causes a total mental rupture with reality, which you then impose on the outside world, insisting that it conform to your delusional inner fantasies—or else you seethe in silence, nursing secret resentment, embittered that you are not getting the attention or praise you believe you deserve. (Narcissism experts are nodding their heads.)

This is different from pride. Pride is first. It goes deeper than vainglory. It is harder to detect, subtler, and more profoundly embedded in the structure of our fallen inner life. Fundamentally the total pollution of the nous or spiritual intellect, pride involves a catastrophic metaphysical fall: the failure to see that Christ, as the true source and final end of all that is good, belongs at the centre—not you. This primary loss of noetic vision warps the very core of your being. It is the ur-error, the error of Lucifer. Indeed, once pride has convinced you to place yourself at centre and not God, you lie fully open to the devil’s next attack. Manipulating your soul’s natural power of desire by harnessing sensual pleasure against you, the devil induces a second fall: the belief that sensory and not intelligible reality is primary. After that error, two more follow in quick, logical succession: first, the error that only the visible, material world is truly real; and then, the error that you are therefore nothing more than your mortal body. This delusion, that you are only your body, sets up a final devastating fall. For mortality does indeed permeate your body of flesh. Therefore, once you have identified with that flesh, you cannot but fear death as the total cessation of your being. You have fallen to the devil’s final trick, the fear of death. You are now completely under his control.

So, pride is the primary fall, corrupting the nous. Vainglory lies downstream, a second-order effect of that more basic corruption. Pride is noetic blindness, vainglory the pursuit of a wicked kind of pleasure that follows upon that blindness.

Despite the fundamental difference between them, pride and vainglory are intimately interrelated, as I have said. They work together to turn us into a Pharisee. To understand how, let us look even more closely at the fall of the nous.

True reality is spiritual. Whatever meaning there is in the material creation—and there is a great deal—is not material in itself, but spiritual. This is not to denigrate the material. It is simply to say that meaning, by its nature, is spiritual, and so, the material world carries meaning not in itself, but insofar as it is the splendour of the spiritual world. The visible reflects the invisible; the sensible reveals the intelligible.

Now, the nous, likewise, is spiritual. It belongs to the spiritual world and is made for meaning. When healthy, it turns its attention to the sensory world and directly intuits the spiritual world that the sensory reveals. In this healthy mode of noetic perception, visible things function as they were made to function: as mediators of the invisible. In other words, a healthy nous possesses a healthy imagination—more precisely, a healthy phantasia, the imagination’s fantasising power. This is the faculty that assembles sense data into intelligible mental images. When healthy, your phantasia presents a mental image to your imagination, and immediately, without attaching to the image, your mind perceives the spiritual meaning it conveys.

This changes after the fall. The nous retains its innate capacity for knowing, but now, cut off from direct spiritual vision by the lie that only sensory things are real, it no longer perceives the divine meaning that visible images reveal. Instead, the imagination attaches to the sensory images themselves. They become its primary focus. This is so because the fall of the nous corrupts all its faculties, including the imagination; in the writings of the Fathers, the term phantasia is most often used to describe the imagination in its fallen state, what they call carnal mind. In carnal mind, no longer capable of true imagination, you merely fantasize. You are forced to lean heavily on the image-making power of phantasia, which was never meant to bear such weight. The images your imagination receives become opaque, not revelatory. You think you see, but you are blind, able only to hear a faint echo of true reality.

This epistemic impoverishment is total, fatally extending even to your self-knowledge. For as we have seen, in your delusion you also believe you are nothing but a material body. This leaves you unable, or unwilling, to contemplate yourself as the immaterial nous that you are. Instead, wishing to know yourself in your fallenness, but identifying with your body, you draw on phantasia to cast yourself as a bodily image. You go from being a self to becoming a self-image—an act of supreme spiritual devastation.

In other contexts, this process is known as original sin. It begins at birth. As a baby, your infant reason developed in tandem with a fleshly pleasure-pain dynamic. Discerning what feels good and what does not, what belongs to your body and what does not, your phantasia drew on these sensory inputs to sketch the outline of a self-image. You slowly acquired a sense of self. As you matured, your knowledge of pleasure and pain expanded beyond the physical to encompass ever subtler attractions and aversions—emotional, psychological, intellectual—and all along, your phantasia continued its work, embellishing your self-image, reinforcing it, refining it. As a result—usually quite unconsciously—you now fantasize about yourself constantly.

And by that I mean, you fantasize about your body. For your self-image is indeed a self-image. Using phantasia to know what is beyond its natural scope, your nous has quite literally fleshed itself out, and has anchored its identity in a mental image of your visible, tangible body. This body-fantasy is your sense of self. When we speak of the sense of self, or the ego, or the old Adam, or the flesh, or the self-image, these are not vague metaphors. They all refer to an actual—if imaginal—reality: a mental image of yourself as a material body. And that fantasy body-image is always there, masquerading as the core of your being.

This is where vainglory comes in. Once the fallen nous, out of pride, has usurped God and enthroned a fantasy body-image at centre, vainglory gets down to work. Desperate to extract whatever pleasure it can from admiration, attention, or notoriety, vainglory plays with that self-image like a paper doll, dressing it up in various guises, constantly reconfiguring, repositioning, and embellishing it—idealising it into an Apollo (narcissistic perfection), or degrading it into a Satyr (animalistic indulgence), or even, perversely, distorting it into a Medusa (monstrous self-hatred). Having privately adorned the body-image to its satisfaction, vainglory then projects that image outward for public display, unleashing the behavioural effects described above.

It is to help you recognize this inner fallen dynamic—this interplay between nous and phantasia, pride and vainglory, self and self-idol—that the eastern Christian tradition warns so strongly against employing phantasia during prayer. Strive to banish all images from your mind, and you’ll soon discover that the most stubborn—the most resistant to banishment—is your self-image. This idol, you realize, is the actual object of your worship. You think you are praying to God, but you are not. Like the Pharisee, you are praying to yourself. This realization can trigger profound and lasting shame, but the tradition teaches that this is purifying, a fire through which everyone must pass. For if God is to reign in his rightful place, first all idols must be destroyed. Yet even so, the tradition says pride is the ultimate enemy. It is what created and enthroned the self-image, the god-idol toward which you offer your life’s worship. Therefore, even after you have vanquished vainglory and shattered your idolatrous self-image, the root cause of all sin remains in you. Moving up the ladder of spiritual purification, you have not yet reached the top as long as you refuse to relinquish God’s throne at centre. Pride is still there, polluting your being.

Now, the question of who ultimately is to blame for the infernal pride within us is a tremendous mystery. I have called it original sin, and perhaps that is what it is, simply a brute fact of our fallenness, that pride should create the fantasy body-image and then, with vainglory’s help, self-righteously worship it as a false god. It may be a built-in feature of humanity as it currently exists. Still, without a doubt, parents or other authority figures help the process along. Whether by aggrandizing us, denigrating us, or even nurturing us in a way the world would consider balanced, however it manifests, the influence of others shapes our self-image.

Including, of course, the influence of the Church. And here is where we reach the real point of the parable—indeed, the whole crux of the Saviour’s message. Because it is not just pride or self-righteousness in general that is in his sights. It is religious pride, religious self-righteousness. This is clear from the fact that Christ has chosen to make his main character a Pharisee.

As we have seen, the Pharisees were genuinely pious. They adhered meticulously to inherited tradition. St Paul, who described himself as ‘a Pharisee, the son of a Pharisee’, called that Jewish movement ‘the strictest sect of our religion’. He praised the Pharisees’ belief in the resurrection, spoke approvingly of having been educated by them ‘according to the strict manner of the law of our fathers’, and said they were truly ‘zealous for God’. By making his exemplar of self-righteousness a Pharisee, Christ is clearly signalling that his target is religious pride.

Christ could hardly be any clearer, yet even when we recognize the Pharisee to be a symbol of bad religiosity, we try to wriggle free. Instead of seeing him in ourselves, as Christ demands, we project him onto others—especially onto people who live outside what we imagine to be the One True Church. For example, standing at the Liturgy, we hear the parable being proclaimed and imagine that its message is targeting Jews. As if Christ wants to console us Christians by pointing out that whereas their Judaism is a religion of self-righteousness, our Christianity is not. But that is absurd. Was the New Testament written for Jews? No—it was written for Christians. And so, in this parable, we Christians are the Pharisee. Or else we try to wriggle out the other way, admitting that, yes, the Pharisee stands for Christians, but they are those other Christians—the Catholics, the Protestants, whoever. Not us. But that is also totally wrong. Every Church is stained with the sin of religious pride. Whatever Christian tradition you follow, you must reckon with your inner Pharisee.

The parable exists to reveal this to you. ‘Two men went up to the temple to pray,’ Christ says, ‘One was a Pharisee and the other a Publican’. We Christians are the Pharisee. Christ has diagnosed self-idolatry in us—and this self-idolatry is polluting our prayer. After all, the two men went up to the temple to pray. And both men are praying. Christ is not comparing those who pray with those who do not. His contrast lies between two types of prayer—one right, one wrong. And since we are the Pharisee, ours is the wrong kind. Our souls are leprous with religious pride, disfigured beneath ornate vestments of false piety, and so we are praying to ourselves, vaingloriously worshipping a false self-image. Our prayer needs to be purified.

This is why St Gregory Palamas, in his sermon on the parable, says that it is particularly significant that, to pray, the two went up to the temple. Temples are where purification happens—where unholy things are made holy. He calls the temple ‘an image of the saving ascent of the spirit during holy prayer, and of the forgiveness it brings.’ And remember, when the Gospel contrasts two characters or images, it is describing two poles of a single dynamic. Here we see this working itself out in the mystery of prayer. Prayer is not static, not simply pure or impure, full stop. It is a bipolar dynamic. It has either been purified, or is being purified. In the case of the saints, it has been purified. For everyone else, real prayer is prayer undergoing purification—a spiritual dynamic involving, in one soul, both a Publican and a Pharisee.

Yes, we Christians are the Pharisee and must repent of it like the Publican. This is especially true if you are an Orthodox Christian like me.

The more I contemplate it, the more I realize how crucial the parable is for us Orthodox. This is because, though it grieves me to say it, we are saturated with religious pride. It tarnishes everything we do and threatens to render our very real virtues null and void. Who can deny it? In conversation with one another; in countless podcasts, books and articles; and, most damnably, even at worship, whether in the open or in our hearts, we enjoy nothing more than luxuriating in the Pharisee’s prideful prayer. All too often—always, really—this is how we Orthodox pray: ‘We thank you, O God, that we are not like the rest of mankind—not like Jews or Muslims, or Leftists or Modernizers, or Non-Chalcedonians or Ecumenists or Calvinists, or any kind of heretic—and certainly not like those Roman Catholics over there. We fast twice a week—they no longer do. We maintain the patristic dogmas to the letter—they have deviated. Our ancient Liturgy remains unchanged—theirs has been corrupted.’ We think we are praying to God but, animated by the Pharisee’s satanic self-regard, we are only praying to ourselves.

It is the great stain of our Church. Through the providence of God—which, superficially at least, can seem more like a series of historical accidents—untold generations of the faithful have handed down to us an integral tradition of Christian prayer and worship. And though we pretend to thank God for Holy Tradition as the divine gift that it is, in our vainglorious hearts we credit ourselves with having preserved it intact. We exult in our special genius, our mystical insight, our martyric courage, glorying in our Orthodox phronēma, or mindset, just as the Pharisee gloried in his own virtues.

Now, perhaps you disagree. Perhaps you are inclined to think instead, ‘But I have been baptized into the One True Church. It is simply the case that I am not like the rest of mankind. We are the true Israel, the Chosen People of God.’ If so, listen to the voice of the Forerunner crying out in the wilderness of your religious pride: ‘Do not presume to say such things to yourself. For I tell you, God is able to raise up children for the Church from these very stones.’ You see? Religious pride is the Gospel’s diagnostic focus from the very first page. The axe is laid at the root of that tree from the very beginning. And so, you must heed the Baptist’s voice, first by understanding that you are the Pharisee. You must, in that way, undergo his baptism in a spiritual sense—or else your baptism into Christ is half-hearted and merely material. Certainly nothing to glory in.

Or, if you absolutely must regard yourself as better than the rest of mankind, at the very least, think of it this way: it is precisely because you are a member of the One True Church that Christ delivered this parable especially to you, with your Pharisaism especially in mind. Let that be your mark of distinction. And once you do, read the parable! It declares its meaning quite openly. We are the Pharisee. Step out from behind the icon-screen of religious pride that we have erected between ourselves and the truth, read Christ’s blistering critiques of the Pharisees, and you will feel the sting of the accusation. Matthew chapter 23 is especially instructive, but there are several others. A few basic vocabulary substitutions are all it takes to translate Christ’s words against the Pharisees of his day into a perfect mirror of our own attitude: trusting in Holy Tradition as proof of our righteousness, while despising the rest of mankind.

The online space is, of course, where this is most rife. In the name of evangelization and catechesis, Orthodox influencer-Pharisees traverse broadband and Wi-Fi to make a single convert—but by filling that person’s head with traditionalism and triumphalism, they render him twice the child of Gehenna that they are themselves. Not to mention their heresy-hunting. Endless, paranoid heresy hunting! But no—now I am projecting, and I must not point fingers. We are all Pharisees. We cannot help ourselves! It is almost foreordained that, over coffee after the Liturgy, our conversation will swiftly turn toward something disparaging of outsiders. Who among us has never indulged that particular pleasure? It is a shameful compulsion. Not that we would ever bring it to confession. For do we even consider it a vice? In some quarters, it is treated as the supreme virtue. How else, we tell ourselves, will we preserve our tradition? And how much energy do we spend debating the finer points of liturgy, fetishising particular iconographic or ascetic canons, insisting on our preferred order of clerical vestments, and the like? You would think we took pleasure in broad phylacteries, places of honour, and greetings wrapped in strict presbia. As for those of us who preach, how much do we love to begin our sermons, ‘We in the Orthodox Church…’, and then to focus less on the Gospel itself than on Church tradition, or on re-anathematizing all those outsiders who are in total error and diabolical schism? As a preaching strategy, it feigns self-judgement: We aren’t living up to our glorious tradition! But in truth, it flatters our collective ego: Look how right and true and glorious we are! We have the only true tradition!

Every good parish priest or saintly bishop I have ever spoken to about this agrees, and I have known a fair few. The online Orthosphere in particular draws their ire, but they are equally fed up with the number of outright narcissists in their own ranks, and deeply concerned at the swelling tide of ego-driven zealots putting themselves forward for baptism and ordination. Yet a clergyman is often hamstrung. Like the rest of us, he too usually identifies with our vainglorious ecclesial self-image—indeed, sometimes more so, by dint of his position. The thought of the Church’s Pharisaism causes him too much cognitive dissonance to address the problem openly. Not because he does not see our religious pride, but because he, too, is caught inside it—and anyway, he knows that, should he say anything, parish pitchforks are always at the ready. Or let us imagine he is determined to help his flock overcome religious pride and musters up the courage to deliver a sermon aimed at steering us away from it. But to what effect? He knows that at that week’s coffee hour—just like last week’s—we will start praying to ourselves once again.

We cannot help it. We are formed by religious pride. It is the air we breathe and the water we swim in. There is thus a contradiction at the heart of our tradition. We teach people they should be humble, but with our very next breath we say how brilliant they are to have joined the One True Church—unlike all those unfortunate outsiders, we add, who are, sadly, quite deluded, and even, if we are being honest, a little malicious. This is nothing short of disastrous. In a collective fall that mirrors the fall of the individual nous, we have fantasized an ecclesial body-image for ourselves. Quarried from imagined memories—of emperors and kings, of Church Fathers and Ecumenical Councils, of chosen nations and heretical barbarians, of noble patriarchs and dastardly popes—it is enthroned at the heart of our communal imagination, an inner temple opulently adorned with gently swaying chandeliers, faded medieval mosaics, shallow domes, and the like. We dress the image in robes of shimmering brocade and, manipulating it like a marionette, use it to stage a self-aggrandizing and largely invented drama, a costume drama of good versus evil, one in which the good radiates outward from the Golden Horn, and the evil, well, as we all know, evil is not a substance in itself. Evil is merely privatio Bosporī—an absence of the Good.

Like all self-images, our ecclesial self-image is an idol. It has turned us into the Pharisee and so we Orthodox are not worshipping Christ in spirit and in truth. Just as in our personal noetic blindness, we unknowingly worship our own bodies, so too in our religious pride, we do not worship the Spirit of Christ, but only a fantasy-image of his body, the Church. And I stand as guilty as the next man! That’s the point: we all do. And our hearts will be closed to true righteousness, the Gospel says, until we stare this shameful fact full in the face.

In the meantime, religious pride has polluted our prayer. As St Gregory says, prayer should be a saving ascent. But that is denied us. We have already made a damning ascent—an upward movement of the spirit that is in truth the spirit’s fall—and so Christ has already judged us.

‘The Pharisee stood praying to himself,’ he says. Think about what that means. Though we invoke the divine name, ‘I thank you, O God!’, we are not, in fact, praying to the One True God. Rather, in our religious pride, we are instead praying to ourselves—to that ecclesial body-fantasy, that Church-idol, that false god enthroned on the altar of our collective self-image. That is what we worship as if it were God. And this is so before we utter our false prayer. Christ does not condemn our prayer after the fact. He condemns our prayer in advance. He accuses the Pharisee before he has even opened his mouth: ‘The Pharisee stood praying to himself.’ In fact, it is not really our prayer that Christ’s words condemn. His words condemn us. He has already looked into our ecclesial heart and seen there the idolatrous self-worship that corrupts it. We arrive at the Liturgy already convinced of our collective righteousness, and our prayer only manifests it. ‘We thank you, O God, that we are not like the rest of mankind!’ Dig down deep enough and you will find the hidden source of that Pharisaical voice inside yourself, because it is there—inside us all, informing everything we do.

Once you have uncovered it, let St Gregory cauterize the ulcer of your ecclesial self-conceit with these scriptural warnings:

‘Everyone that is proud in heart is an abomination to the Lord.’ (Prov. 16:5) ‘Woe unto them that are wise in their own eyes and prudent in their own sight.’ (Isa. 5:21) ‘We have done wrong, and we have all become unclean, and all our righteousness has become like a filthy rag: and we have fallen as leaves because of our iniquities.’ (Isa. 64:5-6) ‘When you do all that is required of you, you are to say, “We are servants of no worth, for we have done what we were obliged to do.”’ (Luke 17:9-10)

Each of those verses—and there are hundreds more—should land like a clenched fist, beating violently against the breast of our pride. Each flinty blow should let flash a spark of spiritual poverty in us, illuminating the true inner kingdom beyond all egoic fantasy. This is the kingdom that Holy Tradition is meant to unveil in us, in accordance with the Saviour’s words, ‘Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of the heavens.’ Poverty of spirit is what remains when, hearing your inner Pharisee damn himself without knowing it, in full knowledge your inner Publican collapses to his knees, ashamed at the depth of his infernal pride. And until we acquire genuine poverty of spirit, our religious pride will continue to poison our prayer.

Which is catastrophic. Prayer is vital. It is how we fulfil the Saviour’s greatest commandment: to love God with all our heart, mind, soul, and strength. And because it is only through divine love that pride is destroyed, this means that prayer is the very thing that purifies us of pride. Yet here lies the catastrophe. Religious pride has poisoned our prayer. The antidote to the poison has itself been poisoned! We are trapped in a spiritually deadly vicious circle. You now understand why Christ criticises the Pharisee as much as he does, how the parable reveals the true depths of our sinfulness. We are wholly polluted, wretched men that we are, and echoing another notorious Pharisee our spirits cry out, ‘Who will deliver us from this body-image of death!’ For we are indeed enslaved to an idolatrous ecclesial body-image, enslaved to communal pride, enslaved to a collective fear of communal death—and thus enslaved to the devil.

The one thing that can save us, holy prayer, has been corrupted. Until it undergoes purification, it cannot serve its proper function as the only antidote to pride.

It stands to reason that only someone who is not infected with pride can heal us of our pride. Only someone whose prayer is itself pure can purify ours. And Christ, of course, is that person. Only he is perfectly free, sinless and pure, so only he can redeem us from our enslavement to pride.

But again, what does that actually mean? It means: humility. Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God, power and wisdom that are shown most clearly in humility. The Word of God—the eternal One, the pre-eternal counsel of the Almighty Father, the divine command creating all worlds, the Alpha and the Omega, the meaning of all reality—is humble. Being in the form of God, he does not cling to his high status, fantasizing as we do. Instead, by becoming incarnate within us, he enters the darkness of our idolatrous body-image. He empties himself and takes the form of a slave to sin, becoming a curse for us, becoming indeed sin itself—becoming, as it were, a Publican. Our inner Publican.

Yes, if we are the Pharisee, Christ is the Publican. Which is to say: if our inner Pharisee is the voice of infernal pride that pollutes our prayer, then Christ is our inner Publican, the power of divine humility that descends from above to cleanse our prayer and to save. This is the mystery of prayer and of the parable’s alchemical power. We ascend a Pharisee, but when we allow the Holy Spirit to show us who we truly are, and acknowledge our prayer as the damning ascent that it is, we descend a Publican—and that descent becomes our true ascent. A paradox, perhaps, but only if we read the parable as a mere moral fable. Understood spiritually, the meaning is clear. We see that we are one thing, and we cry out to be made another. We see that we have corrupted God’s original creation by fashioning an idolatrous self-image, and we plead for re-creation: ‘Create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew a right spirit within me.’ Casting ourselves down, we are raised up—and so, through repentance, our downward ascent becomes an upward descent. This is the paradox which, in my view, is what the last line of the parable expresses, when read spiritually: ‘For everyone exalting himself will be humbled, but he who humbles himself will be exalted.’ Being humbled is the power of Christ within you humbling yourself.

In fact, Christ is that paradox. He is the One, in us, who ascends by descending. He enables our saving descent by taking on the suffering of our damning ascent, transforming the penalty of our pride into the path of salvation. He descends into our prideful hell, lowering himself to raise us up into his glorious humility, so that we may abide eternally in him at the right hand of the Father.

To transmute religious pride into humility in this way, Christ must first reveal it to us. And so we feel the initial stirrings of his alchemical grace when the prideful voice polluting our prayer becomes clearly audible to our conscience. What then? Do we turn away in shame? Deny it in self-justification? No. We heed the parable. We acknowledge it—and repent of it. This repentance is the one act of freedom still available to us in our slavery to pride. For as the Gospel teaches, over true humility the devil has no power. And so, by repenting of our inner Pharisee, we unite ourselves with the power of Christ and are able to pray the Publican’s prayer—the Jesus Prayer—in the right spirit.

It is the only way. You either pray the Publican’s prayer as a Pharisee, or else, for you, even the Jesus Prayer becomes Pharisaic, an act of pride disguised as repentance. You might say with your mouth, ‘Lord, have mercy!’, but unless you say it repenting of the religious pride in your heart, then in spirit you are really saying, ‘I thank you, O God, that I am not like the rest of mankind.’ And only when you do repent properly of your religious pride can you fulfil Christ’s instruction to approach God in the way a child approaches his father. This is because penitence in imitation of the Saviour wins us a share of his own filial boldness. Prayer to the Father in the Spirit of his self-emptying Son—boldly, trustingly, as a child to his loving father—is how the Father grants our request for mercy.

Prayer, when performed properly in the Spirit of Christ, is a humble petition for mercy. ‘What father among you,’ Christ asks, ‘if a son asks for a loaf, would offer him a stone? Or if it is a fish, would offer him a snake instead of a fish? Or if he asks for an egg, would offer him a scorpion?’ This is very important to remember. The Church Fathers do not reduce prayer to something merely meditative. They do not portray it as bloodless, or without feeling, or purely intellectual. Our prayer is not Buddhist. It is Abrahamic. As St Cyril of Alexandria says in his homily on the parable, Christian prayer is always worshipful petition:

Let us once again receive the Saviour’s words in both mind and heart. For he teaches us how we ought to bring our requests before him, so that those who practice prayer will not practice it in such a way as to go unrewarded—and so that, by the very practice through which he hopes to receive some benefit, no one ends up angering God, the giver of every good gift from above.

Thus, when we pray, we ask God for something. St Cyril calls what we ask for a benefit and a reward. St Gregory calls it forgiveness. St Theophylact calls it healing. In the parable it is called justification, being made righteous. The Publican, like us Orthodox, calls it mercy. How often in our worship do we cry, ‘Lord, have mercy!’ Mercy, forgiveness, righteousness—all of these words swirl round what is in effect a single reality: divine grace, a share in God’s uncreated life. Grace is mercy, and mercy is what being made righteous amounts to: participation in the righteousness of Christ. This is the benefit we seek in prayer. When we pray properly, therefore, we are asking the One infinitely beyond being to grant us his own superessential infinitude by grace. We must do so literally, and with feeling, which first requires that we repent of our Pharisaism—at every moment. With constant vigilance of spirit, we look for religious pride inside ourselves and, in a Christ-like spirit of humble petition, slay it with the Publican’s prayer. ‘God be merciful to me, the sinner!’

But our prayer so often gets this wrong. We pray for mercy, but we do not do so properly, as a desperate petition for divine grace. We are simply praying to ourselves, saying mercy with our lips, but with our hearts saying, ‘I thank you, O God, that I am not like the rest of mankind!’ And notice, where is the petition in the Pharisee’s prayer? He thinks that because he has maintained Holy Tradition, there is nothing else that he needs from God. We think the same way. We have received the gift of righteousness, and now we just need to hold on and thank God for what we already possess. But this is a sign of delusion, a sign of religious pride.

Everything hinges on this: repenting of religious pride. Because we are Orthodox, whenever we go up to the temple we cannot but bring our inner Pharisee with us. Religious pride is built in. It is what we need to be healed from. This healing happens when that pride is revealed to us through the grace of the Holy Spirit and, acknowledging it at once, we repent. Then our prayers are accepted and we leave justified. But if instead of repenting, we remain grounded in unacknowledged religious pride, then no matter what righteousness we go up with (and we are Orthodox, we go up with a lot!), we come down without any righteousness at all. We become the unwitting victim of that hard saying of Christ: ‘From those who have nothing, even what they have will be taken away from them.’ Another paradox: to have something, and yet to have nothing. Still, do not forget: like us, the Pharisee did have something. The righteousness in which he gloried is a real kind of righteousness, however partial and imperfect. As we saw, the parable loses its force if we imagine he is lying about his virtues. He is not: he fasts, he tithes, he maintains Holy Tradition. Those are real virtues—and in theory, we have them too. And yet, in line with that hard saying of the Saviour, when we lack what is truly everything, penitent humility, then the righteousness we truly possess is condemned as nothing.

Up and down the Church—and within each of us—Holy Tradition has become something demonic inside us. Recall what St Theophylact said at the beginning: ‘When righteousness takes pride as its companion…it turns what was godlike just moments before into something demonic.’ The Pharisee’s virtues were indeed godlike, and so is Holy Tradition. It comes from God and has been maintained down the centuries by the grace of God. But, tainted by self-righteousness, our fidelity to that tradition has taken pride as its companion. We are now the hypocrites, like the biblical Pharisees of old, wearing Holy Tradition as a mask, concealing from ourselves the only vice that truly matters: religious pride.

Before you rush to take up your pitchforks, do not misunderstand me. I am not saying anything against Holy Tradition, nor advocating iconoclasm, puritanism, or radical outward reform. Christ himself says that he does not abolish the Law and the Prophets, so far be it from me to destroy or undermine anything external. As I have said, Holy Tradition is godlike. The problem is not tradition. The problem is us. We are corrupted by religious pride.

And yet, since that inner corruption is precisely what Christ comes to address, there is no need for us to feel any anger or despair about it. Christ is, after all, the One who purifies what is within. He washes the inside of the cup and renews the wine within the wineskin. He is, as St Paul says, a life-giving spirit, the One who revives the dead letter so that it might be fulfilled in spirit. This is the whole meaning of our religion.

And think about it. Imagine we were fully to repent of religious pride and never again prayed this prayer to ourselves, ‘We thank you, O God, that we are not like the rest of mankind!’ What would have to change about Holy Tradition? Which of its external elements would have to be abolished? None. From the sacraments to the icons to the hymns to the hierarchy to the dogmas to the fasts to making the sign of the Cross. None of this has to change. The only thing that has to change is us.

In fact, because this specific inner change away from religious pride is the very heart of our tradition, everything I have written is nothing less than a defence of that tradition. Salvation truly is of the Jews, so the fact that we are Pharisees in need of repentance is not some shocking subversion of the tradition, but precisely what the tradition expects—even intends. For how can we repent of Pharisaism unless we are Pharisees? How can St John the Baptist’s condemnations of religious pride be aimed at us unless our religious pride is what he is addressing? How can Christ’s teachings convict us unless we are the ones in need of them? How will we read St Paul’s admonitions rightly unless we receive them as if they were written directly to us?

I know from long personal experience that Orthodox Christians, including myself, almost always keep the targets of the Gospel’s harshest denunciations at arm’s length—the Pharisees, the Sadducees, the Scribes, the Doctors of the Law. We objectify them as Jews or others whom we consign to the nether-regions outside the charmed circle of the Church, rather than internalize or identify with them, because defending the ecclesial body-fantasy that our religious pride has created is our first priority. And in this way, we re-enact in our own souls the final accusation levelled against them: that they crucified the Lord and calumniated his resurrection.

All right, it is true. You might not be the only thing that needs to change. For there is another parable, earlier in Luke, where Christ admonishes the Pharisees and suggests that some sort of more general change may be required:

‘No one puts new wine into old wineskins, for if they do, the new wine will burst the skins and be spilt, and the skins will be destroyed. New wine is therefore put into fresh wineskins, and both are preserved. But no one, after drinking the old, will immediately want the new, for they will say that the old is better.’

That parable requires an essay of its own. I will end this one with three brief observations. First: if Christ’s image of the wineskin is to be understood spiritually—as, indeed, nearly everything he says should be—then it may refer to something like what I have called the body-fantasy. If so, it confirms that you are what must change. The old wineskin of the idolatrous self-image cannot hold the new wine of Publican humility when it begins to pour in. Second: if we were to commit ourselves fully to eradicating religious pride from within ourselves, and to worshipping more perfectly in spirit and in truth, we might begin to see that much of what we take for Holy Tradition is neither as ancient nor as essential as we assume. And not only that. Seen from the vantage of the Publican—once we have truly learned to pray like him—many of our traditions might be revealed to be the fruit, not of conformity to the mind of Christ as we think, but of religious pride itself. A sobering thought. And finally, third: the required repentance may be nowhere near. It may simply be that we have drunk too deeply, and for too long, of the satisfying old draught of religious pride—and that we will go on saying, the old is better.

This is incredibly helpful- thank you!