In my last written post, Disentangling mind-body dualism, I outlined the Cartesian view of the relationship of the mind to the body. This was in response to a reader’s concerns that my presentation of the Church Fathers’ teaching inclined too close for comfort to the Cartesian view. Legitimate concerns! For as he rightly suspects, Cartesian mind-body dualism is not consistent with orthodox Christian doctrine.

Wouldn’t you know it, about ten minutes after that post hit your inboxes, another loyal reader—one with a truly enviable knowledge of intellectual history—wrote to (gently) suggest that I’d got Descartes wrong. Or rather, that my summary of Cartesian mind-body dualism had not taken into consideration the latest scholarly thinking on the subject. He directed me to a book by Jean-Luc Marion, first published in French in 2013 and translated into English in 2018, entitled On Descartes’ Passive Thought: The Myth of Cartesian Dualism. I promptly acquired a copy.

Marion is considered one of the great minds alive today. I hadn’t read him, but I’d certainly heard of him. He’s unusual: a disciple of Derrida as well as of Daniélou, de Lubac, and Balthasar, Marion is a French philosopher-theologian rooted in the continental traditions of phenomenology and deconstruction who also takes the Church Fathers very seriously, especially Gregory of Nyssa, Dionysius the Areopagite, Maximus the Confessor, and Augustine—all of whom will feature on Life Sentences down the line.

Can I say I’ve read the Marion book from cover to cover? No. But I did cast more than a passing glance at it. Enough to be reminded, once again, how dangerous it is to boil down the philosophy of a titan like Descartes into a few paragraphs. If scholars as distinguished as Marion can claim, as he does in his book, that the vast majority of readers across the centuries have misunderstood Descartes on the question of the unity of body and mind—and if other scholars equally distinguished would argue even with that claim—then where does that leave the little people like us?

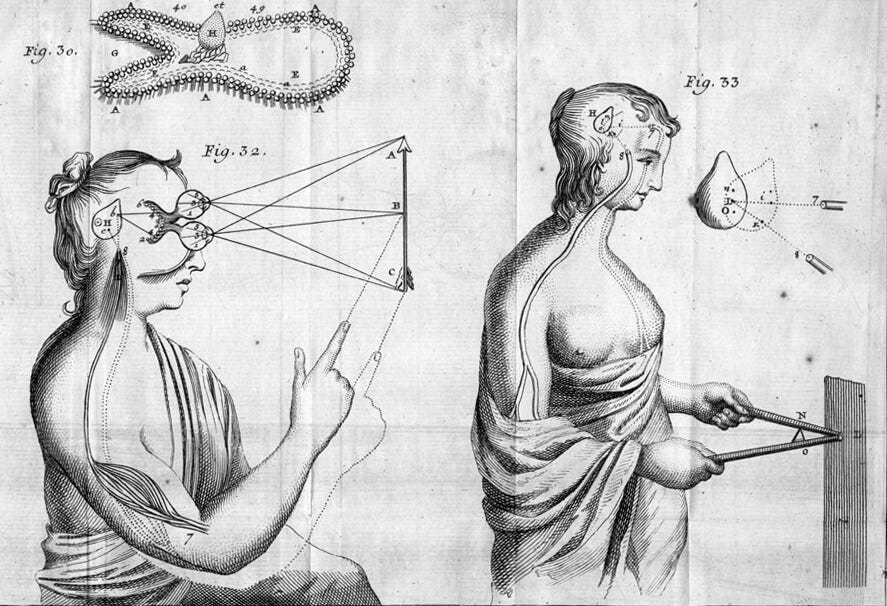

Not that Marion wholly overturns the way Descartes is commonly understood. There are still only two primary created substances: res cogitans and res extensa, the ‘thinking substance’ and the ‘extended substance’. The one is immaterial, the other material; the one wholly rational, the other wholly mechanical, completely describable in mathematical terms, with no remainder.

As we saw last time, Descartes discovered these two primary substances on his quest for self-evident truths—truths that could be disclosed by reason alone and which would therefore overcome the pervasive doubt he believed was the foundation of true intelligence. Cogito ergo sum, ‘I think, therefore I am,’ is the first of these foundational truths that are intuited directly by the mind. This insight, Descartes believed, establishes beyond any doubt that thought exists, what he called the ‘first primitive notion’; thus, he said, the ‘thinking substance’ must exist as well. As for the ‘extended substance’, certain knowledge of its existence rests on the ‘second primitive notion’: geometric extension. Our experience of objects in space confirms this beyond any doubt, particularly through the mind’s intuition of geometric properties inherent in those objects. This is all standard Cartesianism, plain and simple, and the duality it asserts between the two substances is fully consistent with Descartes.

What Marion does do, however, is call into question the cast-iron substance dualism that typifies Cartesianism—the idea that res cogitans and res extensa, and thus the mind and the body, are not only fundamentally distinct but entirely separate. Reading Descartes’ Sixth Meditation closely, where Descartes sets out to demonstrate the existence of material things and the real distinction between mind and body, Marion interprets it in light of Descartes’ final work Passions of the Soul, which deals with the mind’s influence on bodily states and the body’s influence on mental states. Marion argues that, in this later work, a third primitive notion is implied alongside thought and extension: namely, the union of body and mind—which Marion believes has been overlooked by readers of Descartes.

Marion explains that, for Descartes, embodiment itself discloses that third primitive notion. On the one hand, this is obvious. Our minds and our bodies are self evidently united. This is intuited directly by the mind in its experience of being embodied. On the other hand, this raised a dilemma for Descartes: embodiment exposes the mind to experiences like sensations, emotions, and bodily movements, revealing that mind and body are not strictly and absolutely separate. They are separate substances, Descartes asserted, never shifting his views on that; and indeed, for Descartes, res cogitans and res extensa remain the only primary created substances, without a third to ground the union of the two in embodiment. Nevertheless, their union was real. How, Descartes could not say. But because Descartes did affirm the union, Marion shows that he was no dualist; furthermore, because he was unable to explain what he held to be self-evidently true—that, in some way, the body and the mind are one—Descartes was forced to recognise the limits of reason, mathematics, and mechanistic causality.

I hope I’ve understood Marion correctly. Either way, even if standard-view Cartesianism doesn’t do justice to Descartes’ actual thought, as Marion argues, it nonetheless remains true that Cartesian dualism was injected into the bloodstream of Western philosophy—and has therefore been circulating round our minds for nearly four hundred years. The finer points of his arguments may no longer be understood or widely accepted, but Descartes’ conceptions of res cogitans and res extensa—the thinking substance and the extended substance—remain especially influential. Consciously or not, we conceive of our minds, as Descartes did, as essentially ratiocinative, with a capacity for intuition limited to the inherent persuasiveness of logical or mathematical proof; and we conceive of our bodies as parts of an essentially mechanistic material world, fully reducible to mathematical measure, where all non-quantifiable qualities are purely subjective, without any real objectivity.

And so, having done my best to establish what Cartesianism is and that we remain in thrall to it, I can begin to address the ways it fundamentally differs from the teachings of the Church Fathers—and so lay to rest any suspicion that the patristic view of the mind-body relationship is merely rank Cartesian dualism.

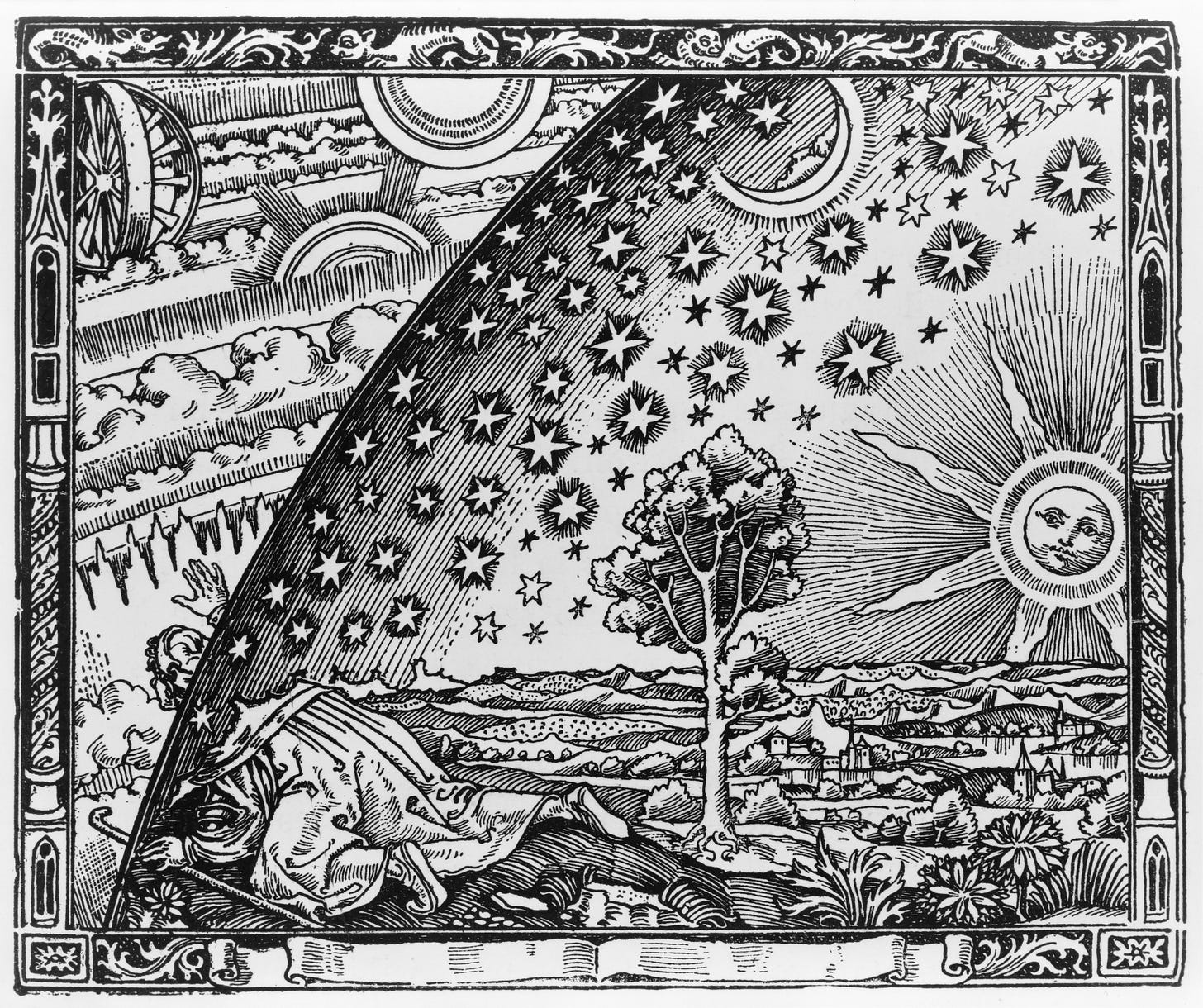

The fundamental difference is decisive: the very notion that there exists on the one hand res cogitans and on the other res extensa would be entirely rejected by the Church Fathers. For them, the mind is not essentially defined by ratiocination, nor is the sense-perceptible world reduced solely to quantity. As we’ve seen throughout Life Sentences, the mind—or nous—is defined not as a thinking faculty but as a seeing faculty: the nous intuitively perceives not logical proofs but spiritual reality. As for the sense-perceptible world, more than what the thinking mind can measure, it is a window onto the spiritual realities that the nous intuitively perceives, a true theophany revealing the glory of God. This divine glory, toward which the mind is innately inclined, is omnipresent—and noetically perceptible, if only the accretions of passionate attachment could be cleared away.

And deep down, we know this. It may be a cliché, but think of a sunset, a rainbow—or any moment of exquisite natural beauty that captivates the mind’s eye and fills it with awestruck delight. The world falls away. You are young again, moved to exclaim in all innocence, ‘Beautiful!’—a wondering child for as long as the moment persists. The moment passes, the world returns, and you’re left with a sense of lessened reality. You were briefly awake, joyful—and now, you’re asleep again. Or consider something similar, but subtly different: instead of a momentary or temporary beauty piercing the everyday, you are presented with a more enduring vision: a landscape, an ocean view, a horizon of water shimmering with light; or something less sublime, a single leaf—anything that invites prolonged contemplation. In lasting visions like these, the effect is different, not childlike but its opposite: you’re world-weary, overcome by yearning, struck as much by absence as by presence, by falling short as by fullness, by lacrimae rerum, the tears of things. In yet another mystery, the effect becomes even more powerful when held in pleasing counterpoint to an artefact of human making, as in a garden, or when framed by a Moorish arch, or simply when the sight is shared with someone you love. It is indeed a mystery, but somehow the human element increases the force of the vision.

As I say, it is a cliché. But what is it, in moments like these, that you are truly seeing? What are you seeing in the sense-perceptible sunset, the rainbow, the leaf, that grants you such knowledge? For it is knowledge that underlies your ‘Beautiful!’ It is knowledge—a recognition of the real—that stirs the heart to compunction when brought face to face with an image of eternity. It is knowledge, real knowledge, a true vision: the mind’s intuition of Beauty.

Look, I’m no philosopher. I’m not able to prove very much. One thing about the Church Fathers is, compared to someone like Descartes they’re far less sophisticated. I’m reminded of an anecdote which John Cassian’s spiritual father Evagrius Ponticus related about St Anthony the Great, the first and greatest of all the Desert Fathers:

A certain member of what was then considered the circle of the wise approached the righteous Anthony and asked him, ‘How ever do you manage, Father, deprived as you are of the consolation of books?’ His reply: ‘My book, philosopher sir, is the nature of created things—and it is always at hand when I wish to read the words of God.’

The words of God, the logoi of created things: these are what the nous reads with illumined intuition when it is pure. And in moments like the ones I described above, the logos of Beauty—surely of all the logoi the most divine—is inscribed so clearly across the matter of sense-perception that even the dullest mind cannot help but read it. And honestly, imagine if, standing before that sunset, your intuitive knowledge of Beauty was contradicted by someone whose starting point was not the faith that comes from inner vision, but doubt. ‘It’s so beautiful!’ he overhears you say. ‘Oh reeeaaalllly?’ he replies. ‘Beautiful, you say! But how can you be sure that there even is such a thing as Beauty? Hmmm? Upon what clear and distinctly self-evident idea can you base such an assertion?’

Ugh.

No, our starting point is not doubt, but faith, because our minds do not start by thinking, but by seeing the invisible. The first primary created substance, I’d argue, is not res cogitans but res noetica, the noetic substance: ‘the heavens’ of our traditional cosmology where God the Father lives in all his glory, as the Lord’s Prayer says. And the second primary created substance is not res extensa, far from it. It is, rather, res theophanica, the theophanic substance: ‘the earth’ that mirrors and reflects the heavenly glory—could we but see it.

Next time, I’ll try to explain what the implications are for the relationship of the mind to the body.

Thomas, I wonder if you are aware of the writing and thoughts of Iain McGilchrist. I think there is a fair degree of overlap with what you are saying here