Five days ago, as happens every year on Christmas Day, the Christ Child was born anew in the holy cave of our innermost hearts. Yes, the Incarnation of the Word indeed took place in history over two thousand years ago. Yet this primary Incarnation occurred so that, by faith, Christ might be born in us—year by year, day by day, moment by moment. This is a secondary Incarnation, as it were, transforming our bodies into his blessed body and our temporal lives into his eternal life—provided we follow his commandments and live faithfully the life that is in him, in conscious cooperation with his Holy Spirit.

That divine life that is in him, and which is disclosed in his commandments, is our inner light—which we then disclose, in imitation of the Saviour, through acts of love and self-sacrifice. We let our light shine so that all who see us might glorify our Heavenly Father. This glorification of Almighty God is the same that the holy angels render at every instance of the Word’s Incarnation. Two thousand years ago they exclaimed it to the shepherds: ‘Glory to God in the highest! And on earth, peace! Among men, goodwill!’ Today, before the mystical transformation of the holy oblation, we will join our voices with theirs: ‘Holy Holy Holy, Lord of Sabaoth! Heaven and earth are full of your glory! Hosanna in the highest!’ And at every moment and with every breath, as we worshipfully, indeed angelically attend to the divine Word in our hearts, the Spirit prays within us: ‘Glory to you, O God, glory to you!’ Through this glorification, the Holy One who dwells in us draws us ever closer into perfect union with himself.

The Incarnation, then, is one dimension of a much greater mystery of glorification, as St Maximus the Confessor teaches. He writes, ‘The Word of God, who is God, wills to accomplish the mystery of his embodiment always and in all things.’ This greatest of all mysteries—God’s embodiment—begins for us with Incarnation, but from there it proceeds through the Way of the Cross, to Death and Descent, then to Resurrection and Ascent, and only culminates when God is finally All in All. In that final glory, the new heaven (which is within us) and the new earth (which is outside us) will be united in His Body, the Church. The two become perfectly one in the glory of the One Who Is: the New Adam, the Man from Heaven, the Inner Man Lifted Up, Christ our God.

This great mystery—the fullness of our faith in Christ—is the Gospel that St Paul speaks of in today’s Epistle. He says he received it not from human hands, not from flesh and blood, but in a revelation from the Ascended Lord himself. To a man who never knew Christ on earth, Christ revealed his heavenly glory, so that we who cannot know the earthly Christ in the flesh may know the heavenly Christ in the Spirit. To a man who persecuted the Church (and in so persecuting the Church, persecuted Christ), Christ gave the honour of being his chosen vessel to the gentiles, so that we gentiles (who persecute Christ every time we sin) might be vessels of Christ’s boundless mercy. Christ, who set apart St Paul from his mother’s womb, has set each of us apart as well. Christ, who called St Paul, calls us too—through his grace.

So yes, in the feast of the Nativity, we contemplate a great mystery. The babe in the manger, the Lord come down from Heaven, truly is the beginning of Christ’s saving work. And yet, what follows next? That’s what today’s Gospel reveals.

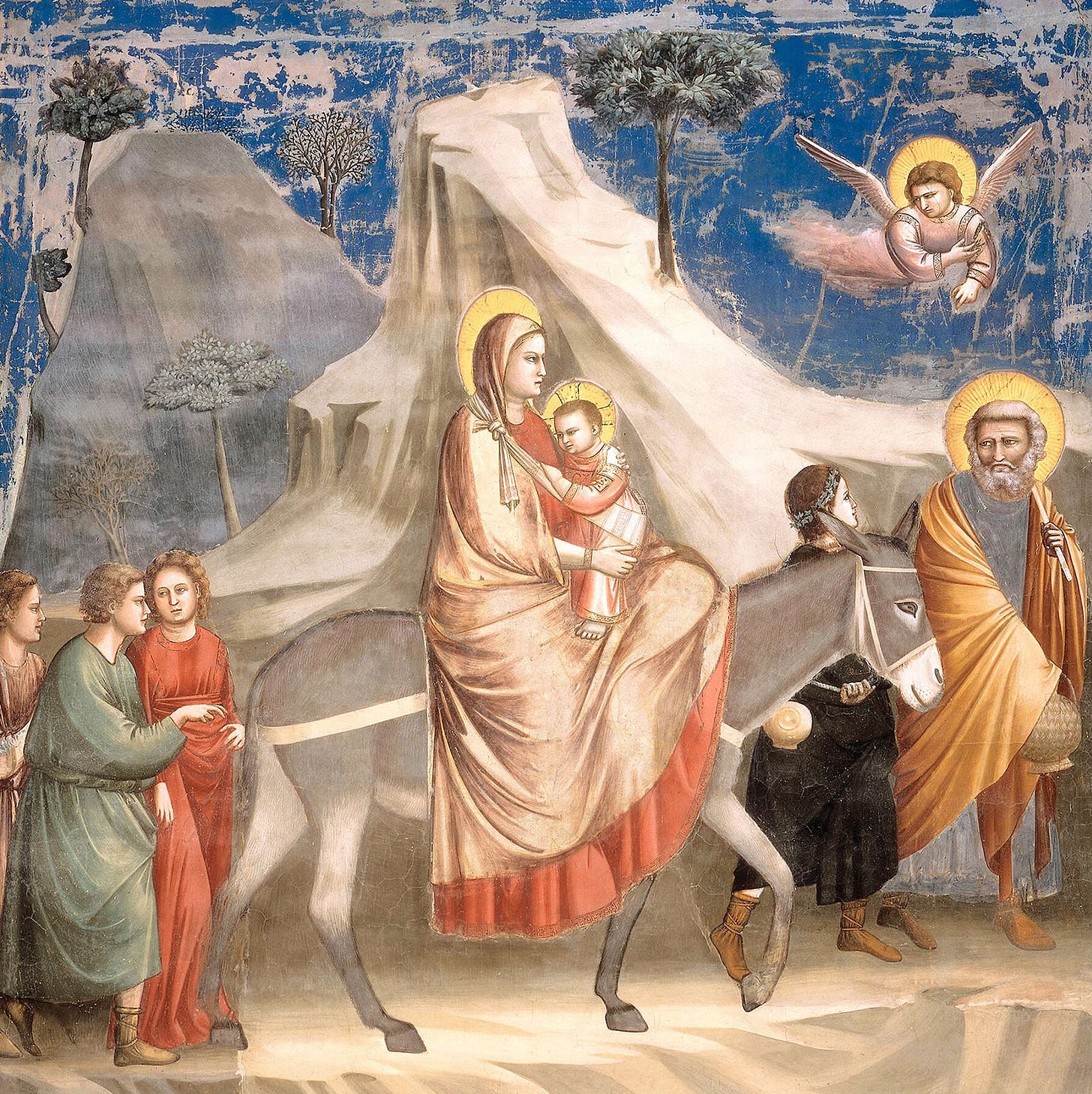

The Magi have just departed, leaving behind their three gifts: gold, frankincense, and myrrh. Gold because Christ is King. Frankincense because Christ is High Priest. And myrrh because Christ has come to be killed for the salvation of the world. The Magi are the first to understand who the Holy Child is: the Priest-King who offers himself on the altar of the Cross. Understanding this truth, they believed, and believing it, they bowed down in worship—just as we do today.

Yet wherever there is this true faith in Christ, the Evil One is near, scheming to undermine it. It is as though the devil can detect faith as one might smell the stench of decay, and indeed our faith, which is life-giving to us, is life-threatening to him. What is fragrant to us—faith in Christ—is putrid to him; what is nourishment for us—the Word of God—is for him starvation. The slightest whiff of faith is enough to incite his desperate fury, and he will stop at nothing to track it down and kill it. So we must remain vigilant.

In the story, King Herod is the devil’s puppet. Working through King Herod, when the devil first hears the Magi announce the birth of the promised Messiah, he attacks the Magi with charm and flattery. If he can manipulate Herod to get the Magi on side, then destroying the Holy Child will be no trouble at all. And who among us has not heard the devil’s voice whispering in his ear when our selfish, materialist, grasping ego tries calmly to reassert control over us after we’ve felt the pull of faith? For that is who Herod is inside us: our fallen self, which St Paul calls ‘the outer man’. He enjoys being in control, even though, like Herod, he is a fraudulent king and ultimately a usurper; the birth of the Lord in our soul spells his doom, and he knows it. The devil easily manipulates this egotistical fear in us, the fear of losing our privileges, of giving up our creature comforts, of putting others first. And as I say, at first he tries rather calmly, and even pleasantly, to talk us out of keeping our faith.

Well, in the story this first plan fails. The Magi are warned by an angel to stay away from King Herod, and they heed the warning, so the devil’s plan is thwarted. Our guardian angel helps us in the same way. If we listen closely to our conscience, we will hear our angel guardian warning us not to return to our old, egotistical, pleasure-seeking patterns. Instead, as the Magi were advised, our angel advises us to depart to our own country via another way—that is, the Lord’s way, the Way of the Cross. This is the path of self-denial, sacrificial love, and unwavering trust in God, a path that leads us to our true homeland, namely God’s eternal kingdom.

Having failed by flattery, the devil moves to Plan B. The story tells us next that Herod gets extremely angry—and never forget, all violent wrath comes from the devil, who, according to the Desert Fathers, is actually made of anger. In his rage, Herod tells his soldiers to scour Bethlehem and the surrounding countryside. He orders them to kill every baby they find under two years of age, certain that the Messiah will be among them. The soldiers follow the king’s evil command to the letter. Tearing babies from their mothers’ breasts, they put them to the sword, a horrific event known as the Massacre of the Innocents. Fourteen thousand infants were murdered that day, each one of them a martyr in the memory of the Church. We commemorate them on this day each year, the 29th of December.

But this tragic event is not only an historical atrocity. It also serves as a vivid image of the spiritual battle waged in our own souls. We experience the same massacre mystically when, realising that we are truly committed to the Way of the Cross, the devil sees our refusal to be lukewarm in our faith and so stirs up the Old Man within us into a violent rage. He attacks our fallen, sinful minds with thoughts of greed and fear and lust and envy, so remorselessly that it can feel as if every good impulse inside us is murdered, every pure and infant-like intention slain before it can mature into action. We are left bereft inside ourselves, wailing in silent but profound lamentation. We mourn this violent upsurge of passionate temptations, and weep over the loss of that innocence which we had only recently recovered. This is an experience that perhaps you who are new to the faith—the newly baptised and chrismated—know all too well.

If it were not for the intervention of our guardian angel, I don’t know how any of us could survive such an onslaught. Yet in the story, an angel warns St Joseph of Herod’s plot in a dream; and in our own lives, our guardian angels once again give us the word of wisdom we need to preserve our faith in Christ unmolested for as long as the fearsome trial lasts.

And what is this word of wisdom? ‘Take the young child and his mother and flee to Egypt.’

There’s so much that could be said about this particular episode in the Gospel. For example, notice all the echoes from the Old Testament story of the Twelve Tribes’ descent into Egypt, the story that spans the end of the Book of Genesis and the beginning of the Book of Exodus. There a man called Israel, father of a son called Joseph, goes down into Egypt to seek protection from a noble king; here a man called Joseph, the guardian of a child who is the true Israel of God, goes down into Egypt to escape a wicked king. There a wicked Egyptian king, for fear of being overthrown, slays all the Hebrew children; here a wicked Judean king, for fear of being overthrown, slays all the children of Bethlehem. There a prophet, destined to save his people from slavery, is adopted by the king’s daughter; here a prophesied Saviour, destined to rescue all people from slavery to sin, is adopted by a man who is betrothed to the true and blessed daughter of the Eternal King. All these echoes between the Old Testament and the New, with all their thematic and narrative reversals, remind us that Christ’s coming is the fulfilment of the Law, that the spiritual realities which, in the Old Testament, are only foreshadowed, in the Gospel are revealed fully illumined.

But notice this also. The angel doesn’t say, ‘Take your wife and son.’ He says, ‘Take the young child and his mother.’ This demonstrates an important theological truth. St Joseph is not the child’s father. The child’s father is God the Father Almighty. And his mother is not St Joseph’s wife, but our All-Holy Lady, the Theotokos and Ever-Virgin Mary. These are, for us, dogmatic absolutes. Yet in themselves, dogmas don’t go very far. Their real power lies in being put into practice. Which is to say, it isn’t enough simply to give rational assent to the Church’s dogmas. We must use the dogmas. We must incorporate them into our spiritual lives, contemplate them in faith, and with intelligence turn in prayer to the ones whom the Church teaches us to worship or to venerate.

And here lies the key to the angel’s word of wisdom. The angel knows that a terrible trial is coming. The devil is preparing an all-out assault. Satan’s goal is to snuff out the light of Christian faith that glows, however dimly, at the centre of your heart. He wants you to despair, to give up, to betray the Lord as Judas did, who then went and hanged himself. That’s what the devil wants for you. But you are not powerless against his schemes. Heed your guardian angel. ‘Take the young child and his mother and flee to Egypt.’

What could this mean for us?

‘Take the young child...’ — that is, your mind’s pure faith in Christ — ‘...and his mother’ — that is, your soul when it is meek and obedient like the Blessed Virgin and when, like her, having birthed the Word of God in the cave of your heart, you preserve him and ponder him there in holy silence.

‘Take the young child and his mother and flee to Egypt.’ Flee to Egypt. In the Bible, Egypt is almost always a place of darkness, idolatry, and wickedness. The fleshpots of Egypt! And indeed, the story says that the Holy Family left by night for Egypt. A flight by night into the land of darkness and idolatry. As a place of refuge for the young child and his mother, Egypt seems an unlikely choice. Why Egypt?

Perhaps an answer can be found in the ancient traditions of the Church—traditions which the Copts of Egypt, for obvious reasons, keep very closely. These traditions say that, after the Holy Family entered Egypt, they moved from place to place. Wherever they went, temples crumbled, idols collapsed, and demons fled as if from fire. So, in this wider version of the story, while up above King Herod massacred the Innocents, down below the Christ Child, preserved by his holy mother, was confronting all the idols and passions which Egypt typifies. Egypt, the land of idolatry and darkness, becomes the unlikely stage for Christ’s triumph over the spiritual forces of evil, prefiguring his ultimate victory on the Cross.

And so we too must flee to Egypt, we must walk the Way of Cross—which, never forget, involves a descent into hell. A saint of the 20th century, St Silouan, when asked for advice on the spiritual life, is famous for providing this cryptic answer: ‘Keep your mind in hell, and don’t despair.’ This is the way. We take the young child and his mother and flee to Egypt; which is to say, holding onto our faith in Christ, with poverty of spirit, meekness of soul, and purity of heart we descend into the darkness of our own sin, illuminating it with Christ’s light, confronting it with Christ’s courage, and repenting of it with hope in Christ’s mercy. And there we must stay—mournfully, patiently, faithfully—until the King Herod in us has finally died.

Let us pray that Christ our God strengthens us by his grace and illuminates us with the light of his saving wisdom, that through patience and trust in his divine providence we might be counted worthy one day of finally returning to the heavenly Holy Land. Amen.