Today, the third Sunday of Great Lent, is dedicated to the veneration of the Precious and Life-Giving Cross. This commemoration must be distinguished from the great feast celebrated each year on the 14th of September, known as the Universal Exaltation of the Cross.

The Universal Exaltation is, to be blunt, a political feast. In the year AD 326 or perhaps AD 327, St Helen — the mother of our patron, St Constantine the Great — visited the Holy Land. There, on the site of Our Lord’s crucifixion and burial, stood a temple to the pagan goddess Venus. This pagan temple had been constructed nearly two centuries earlier, part of the villainous emperor Hadrian’s campaign to erase the memory of Christ and to suppress both Judaism and Christianity throughout the Roman Empire.

Well, now the imperial government favoured Christianity. And so a Christian empress, St Helen, acting in her son’s name, commanded that the pagan temple be demolished.

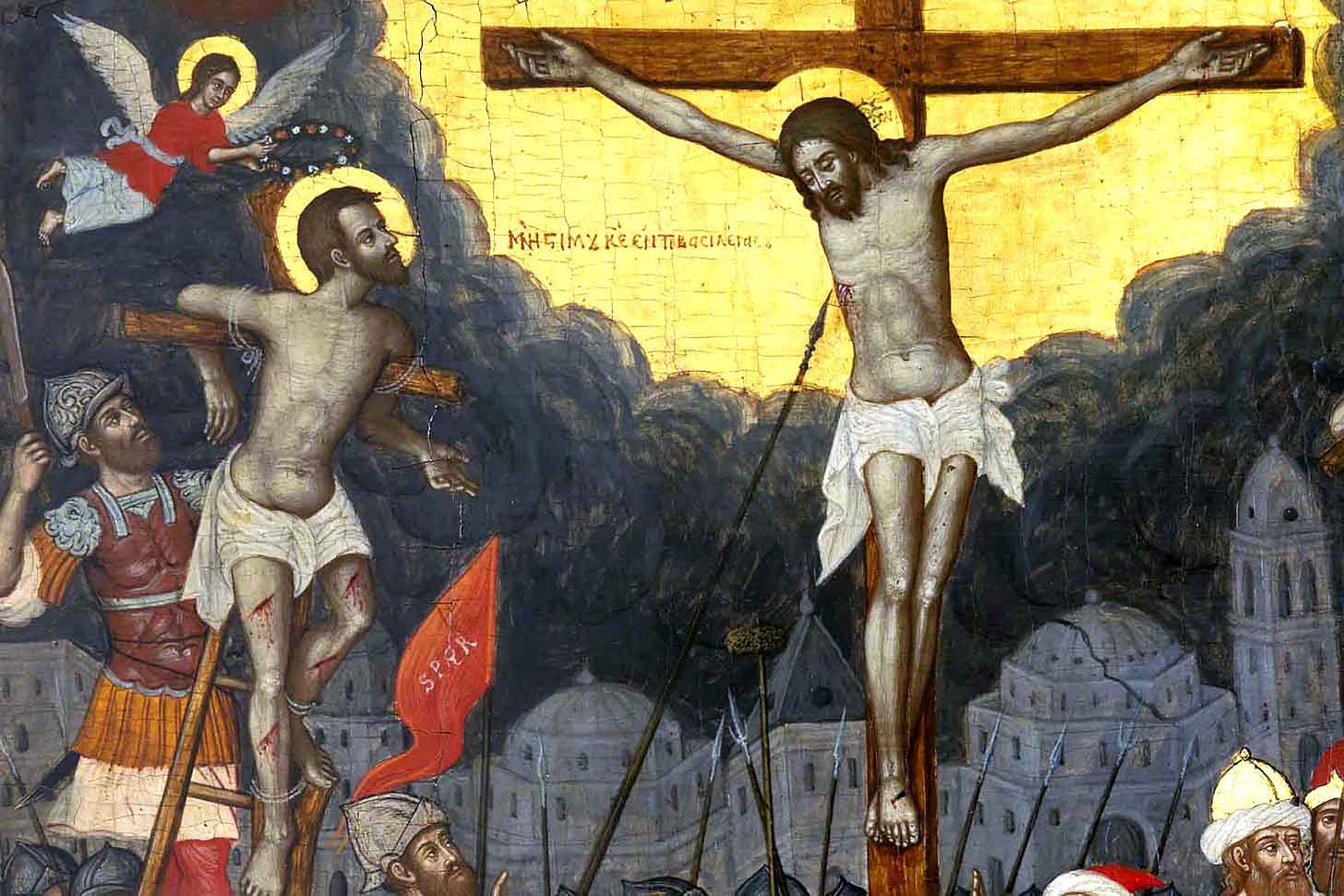

During the demolition, three wooden crosses were uncovered, miraculously preserved beneath the rubble: the Holy Cross itself, and the crosses of the two thieves crucified on either side of the Saviour. When St Constantine heard of the discovery, he ordered that a grand basilica be built on the site: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The Feast of the Universal Exaltation of the Holy Cross was instituted not long after.

Over the centuries, that feast day became associated with the principle of Christian empire. In Byzantium, and later on in Russia, the 14th of September became a kind of imperial holy day — almost a national holiday. The feast celebrated not just the Cross itself, but the Christian empire and the Christian emperors who adopted the Cross as their standard.

But, as I say, this is not what we are commemorating today. Neither are we commemorating the Crucifixion. That will take place on Holy Friday, just under four weeks away.

No, today is something different. Something specific. Today we are commemorating, not the Universal Exaltation, not the Crucifixion, but the Veneration of the Precious and Life-Giving Cross. Σταυροπροσκυνήσεως. Cross-veneration. Our practice of venerating the Cross.

This is something we do constantly. Every time you make the Sign of the Cross, you are venerating the Precious and Life-Giving Cross.

Why has the Church chosen this day for this commemoration, the third Sunday of Great Lent?

Well, it is the halfway point of the Fast. So, we can say that — just as Christ himself is the Alpha and the Omega, the beginning and the end — the veneration of his Cross looks both backward toward the beginning, and forward to the end. The Cross, on which the Saviour stretched out his arms as far as the east is from the west, stands at the centre, embracing all.

First, let us look backward, toward the beginning.

The pre-Lenten season invited us to contemplate four spiritual realities: humility in prayer, repentance from sin, the expulsion from Paradise, and the Last Judgement. Each of these contemplations clearly resonates with our veneration of the Holy Cross.

There is no greater sign of humility than the Cross. On the Cross, our Saviour — the Word of God and true God — voluntarily submitted to death by crucifixion. The ultimate expression of divine self-emptying. On the Cross, the Son of God fully exchanged his heavenly glory for the impoverishment of our mortal condition, thereby granting us that same heavenly glory, insofar as we, with faith in his holy name, lay down our lives for our neighbour.

There is no greater sign of repentance than the Cross. On the Cross, our Saviour — perfect God, sinless man — performed an entirely gracious act of human repentance. The ultimate expression of high-priestly sacrifice. On the Cross, for our salvation, Christ remained obedient to the end, even to death by crucifixion, thereby granting us a share in his unblemished righteousness, insofar as we, with faith in his holy name, remain obedient to his commandments.

And there is no greater sign of the curse of the Fall than the Cross. On the Cross, our Saviour suffered, to the full, the dreadful sentence passed upon us. The ultimate expression of love. Because he was sinless, Christ did not deserve to die, but nonetheless, on the Cross, he became, for us, sin and pain and death. He bore our sins in his holy flesh and nailed them to the Cross, thereby granting us purification from our sinfulness, insofar as we, with faith in his holy name, nail down our own sinful flesh, entering into loving communion with his holy and divinizing body and blood.

So, when we venerate the Cross with our bodies, we bring our spirits into conformity with its divine activity of spiritual humiliation.

When we venerate the Cross with our bodies, we bring our spirits into conformity with its divine activity of obedience unto death.

And when we venerate the Cross with our bodies, we bring our spirits into conformity with its divine activity of conquering death by death.

As Christ says in today’s Gospel: “If any want to follow me, let them disown themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For those who want to save their life will lose it, but those who lose their life for my sake, and for the sake of the Gospel, will save it.”

Finally, there is no greater sign of the Last Judgement than the Cross. But let’s save that contemplation for when we turn and look forward, to the end. For now, let’s keep looking backward.

After those pre-Lenten contemplations, Lent itself began with two further contemplations. On the first Sunday of Lent, we contemplated the Triumph of Orthodoxy: the defeat of iconoclasm, and the godliness of venerating the holy icons. And on the second Sunday of Lent, we contemplated the triumph of St Gregory Palamas: the defeat of his heretical opponents, and the orthodoxy of his teaching on the essence and energies of God. These two contemplations also powerfully resonate with our veneration of the Holy Cross.

After all, the Cross is an icon. And, as the theology of the Church teaches us, the veneration that we rightly show to an icon passes from the material object to its prototype. So, when we bow down before an icon of the Theotokos and kiss it, we are not venerating a painted piece of wood. We are venerating the Mother of God herself. And, through her, we are ultimately venerating and indeed worshipping her Son, our Lord Jesus Christ, whose divine grace fills his pure and ever-virgin Mother to the full.

The same holds true for any icon of a saint. We venerate the image, and our veneration passes, first, to the prototype, the saint, and then, we pray, through the saint, to the source of his or her sanctity, Christ Jesus, the eternal Son of the eternal Father, and indeed to the sanctification itself, the eternal Holy Spirit. All true veneration of any divinized human being is ultimately a means of worshipping the Holy Trinity, who divinizes mankind.

But, what about an icon, not of a saint, but of an event from sacred history?

The same principle applies: our veneration passes from the image to the prototype. Only here, the prototype isn’t a person, but a divine energy: the power or activity of God which that moment in time revealed, or imaged forth; which penetrated the darkness of temporal ignorance like the light of dawn through a window; and which, until its manifestation and activation in time, had remained hidden in the pre-eternal counsel of the Holy Trinity.

How many sacred events do we venerate in this way? Too many to name! Events from our Saviour’s life; events in the history of the Church; even events that took place long before the Lord’s advent in the flesh. All these events, which unfolded in time, reveal that hidden divine energy: the activity of God bubbling away at the heart of everything that is.

And one way that we participate in that divine energy is by commemorating those events reverently and intelligently. Not only by venerating their icons, but by keeping their feast days, chanting their festal hymns, and making a special effort to receive communion on those days.

For all God’s creative, redemptive, perfective and divinizing activities are the energy of God himself, by which he graciously distributes his very self undividedly throughout all time and creation, down to each one of us. All of this activity unites us and this whole lower world of time, not only to the higher world of heaven, but to the very highest, and deepest, and most inward, and most all-pervading: the eternal life of God.

This powerful truth — that everything that is, exists as the active gift of God’s own life, his own being, his own goodness itself — this truth is what St Gregory Palamas so courageously and triumphantly articulated, and which, thanks to him, has been enshrined forever in the bosom of the Orthodox faith.

And what greater image, sign, symbol — and reality — is there of this all-powerful and heart-convicting truth than the Cross! The Cross, an event in time showing forth a purpose conceived in eternity. The Cross, earthly wood infused with heavenly spirit. The Cross, the Tree of Life! That pure and virginal Tree that bore, nurtured, and let fall — fully ripened — the saving fruit that imparts everlasting divinization.

And most mysteriously, the Cross, an inanimate object that is animated — we might even say — by the soul of the Son of God. For, when we address the Cross in prayer and praise, we do so as if to a living person. As we did last night at vespers, singing:

Shine, Cross of the Lord! Shine with the light of your grace upon the hearts of those that honour you! With love inspired by God, we embrace you, O desire of all the world. Through you our tears of sorrow have been wiped away; we have been delivered from the snares of death and have passed over to unending joy. Show us the glory of your beauty and grant to us your servants the reward of our abstinence, for we entreat with faith your rich protection and great mercy.

So much for looking backward. Let us now look forward.

Looking forward, there is, obviously, Good Friday and the Crucifixion itself. And there is, beyond that, our own deaths. And, at the last, the Final Judgement.

And as I said, of the Last Judgement the Cross itself is something like a prefiguration. “Now is the judgement of the world!” Christ said, as his Passion drew near. “Now will the ruler of this world be cast out. And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.” At the Last Judgement, Christ divides humanity: sheep on his right, goats on his left. And look, there at the Cross are two men: one on his right, one on his left. The good thief. The bad thief. Both suffering crucifixion, just like Christ. Both being judged.

Christ the Crucified One is the Eternal Judge, whose being lifted up on the Cross raises us up either to salvation or to condemnation. We are condemned if, like the bad thief, we respond with bitterness and resentment to the suffering that justly arises from our sinfulness. Mocking Christ, the bad thief said, “Are you not the Messiah?” — and then he demanded, “Save yourself and us!” The fool.

The good thief knew better. “Have you no fear, even of God?” he said to the other one, “Since you are under the same condemnation. And we indeed justly, for we are receiving what we deserve for what we did. Remember me, Lord, when you come into your Kingdom.”

The good thief understood that salvation is not simply liberation from all suffering. Salvation is liberation from sin through suffering. Salvation is to accept, with humility and repentance, the suffering that is the just consequence of our sin. We turn in love toward Christ, with faith in the redemptive power of his Cross, and willingly and indeed gladly become co-sufferers with him.

At the end of the Liturgy today, we will enact the Procession of the Holy Cross. Each of us will be invited to approach and venerate. When the time comes, let us draw near with intelligence, with conscience, and with the fear of God. Let us reconfirm our faith in Christ’s saving work, and renew our commitment to taking up our own cross — dying daily, that we might live forever.

Amen.