What follows is a complete transcript of this week’s podcast episode, which you can listen to in the Substack app or via your preferred podcast platform.

The podcast is designed to be listened to, so I encourage you to listen. But I’m also providing transcripts, as you may want to read along as you listen.

Welcome to Life Sentences, an exploration into the wisdom of the ancient Church Fathers presented by me, Thomas Small.

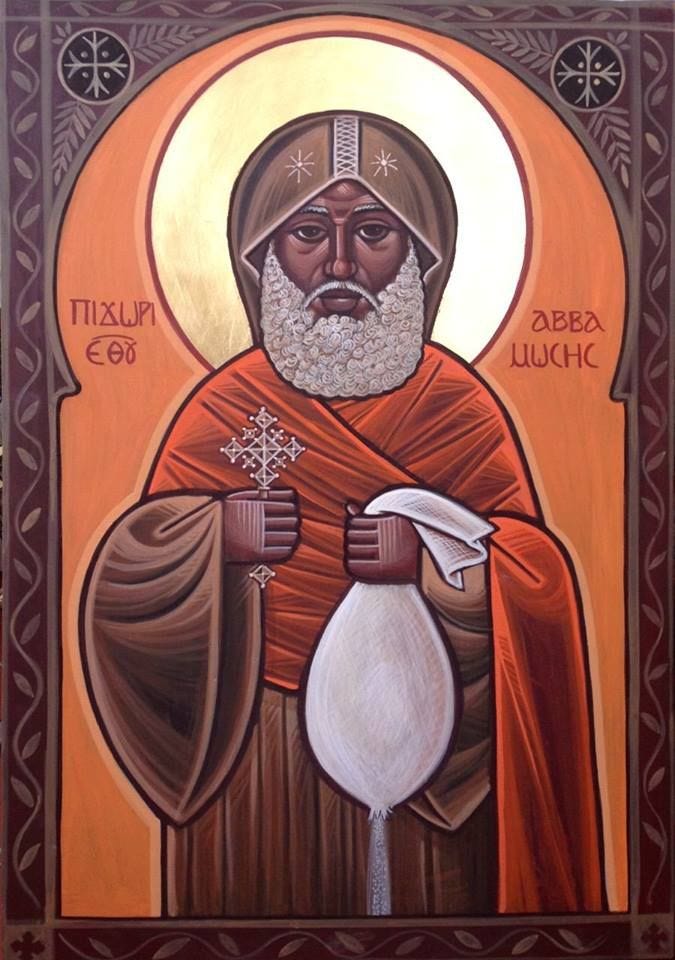

In this episode, St John Cassian, a great master of the contemplative life, introduces us to the man he considered to be the greatest of all the desert fathers, Abba Moses the Black—who reveals the true goal and the final end of all our spiritual striving.

If you’re following the podcast on a podcast app like Spotify or Apple Podcasts or Pocket Casts but have not subscribed to the actual Substack, then I really encourage you to do so. Go to wisdomreadings.substack.com and subscribe. That’s wisdomreadings.substack.com.

Why not take out a paid subscription? It takes a lot of work preparing, recording, and editing these episodes. I love doing it and truly hope this journey into Christian wisdom is a long and exciting one, but to keep it going I will need your support.

Right, having spent the last two episodes getting to know St Basil the Great a little bit and hearing his advice that we all be attentive to ourselves, we’re going to move away from Cappadocia in Turkey and travel southward to Egypt where we will get to know the Desert Fathers. And for the next few episodes, I think, our desert guide will be St John Cassian.

St John Cassian was born in the year AD 360 in Scythia Minor. That’s along the Black Sea coast in what is now Romania. And he lived for 75 years, dying in AD 435 in Marseilles in southern France. In the meantime, he had a very interesting life, full of incident, and played an important role in his times.

Now as I say, he grew up in what is now Romania, but as a young man he left—he and his best friend, his childhood friend Germanus. The two of them travelled south, first to Palestine and then to the Egyptian desert, where they spent seven years drinking deeply of the wisdom of the Desert Fathers.

Many decades later, after St John had founded a monastery of his own near Marseilles, he was asked to write down his memories of the teachings he’d learned in Egypt. And boy did he ever! His magnum opus, The Conferences, is enormous, dense, difficult, and immensely rewarding, containing transcriptions, or so Cassian says, of the conversations he had with the greatest contemplative saints of the desert.

The Conferences is so important and fascinating a text that we will spend the next several episodes, I reckon, thumbing our way through it. So I’m going to save John Cassian’s life story for next time.

This time I want to tell you about the first Desert Father who Cassian interviews, Abba Moses the Black, the star, really, of his Conference No. 1, portions of which we will read through today. What little we know about Abba Moses, we know via the writings of two fifth- and sixth-century Roman Christian historians, Palladius and Sozomen. This version of Abba Moses’s life mainly comes from Palladius’s classic work The Lausiac History, one of the great collections of Lives of the Desert Fathers, written not long after Abba Moses’s death in the early 5th century.

‘There was a certain Moses,’ Palladius writes, ‘a black Ethiopian, who served as houseman to some official in the administration. His master discharged him for exasperating behaviour and for stealing. He was thought even to have committed murder. (I am forced to tell about his knavery in order to show the virtue of his conversion.)’

Now, Palladius then explains that Moses, having joined a group of brigands and indeed having become their leader, and behaving very badly, raping and pillaging and murdering, eventually came to his senses and traveled to the Egyptian desert to live a life of repentance.

Palladius says, ‘Then demons attacked this Moses, trying to draw him back into his old ways of intemperance and impurity. He was tempted to such an extent, so he told us, that he nearly failed in his resolution.’

So Moses goes and confesses to his spiritual father, who encourages him, telling him to stand and fight. Palladius goes on, ‘Moses returned to his cell, and from that hour he practised asceticism more zealously—but continued to be consumed by fire and troubled by dreams.’

Now, fire and dreams is a way of talking about sexual thoughts and sexual dreams. They really plagued Moses.

Palladius says, ‘Once more he went to another of the saints and asked him, “What shall I do, since dreams of my mind blind my reason, because of my customary illicit pleasures?” He was told, “You have not withdrawn your mind from these images, and for that reason you are undergoing this. Give yourself over to vigils, pray and fast, and soon you will be rid of them.”

‘He listened to this advice and went back to his cell. He stayed in his cell for six years, standing in the middle of his cell every night, praying, never shutting his eyes—and yet still he could not control his mind.

‘So he adopted a different strategy. Each night he went out to the cells of the old men, the more ascetic of them who lived especially far off in the desert, and without their knowledge, he took their water pitchers and refilled them, for they have their water a good way off, some two miles, others as much as five.’

Now, as a result of this new regime, Palladius says, this regime of anonymous charity towards the brethren, Abba Moses bested his demonic oppressors, who gave him a severe whooping on their way out of him, beating him so hard that he was rendered paralyzed for a whole year. But he was now free of demonic attack, and indeed was granted the gift of power over the demons, and became a renowned spiritual guide.

When Abba Moses was an old man around the turn of the fourth to the fifth centuries, wild Berber tribesmen who lived in the desert wastes began to harass Roman Egypt. Before long these barbarians had the desert monasteries in their sights.

According to the life of St Moses as preached in the Church: ‘Abba Moses said to the brothers, “If we keep the commandments of our fathers, I assure you by God that no barbarians will come here. But if we do not keep the commandments, this place must be laid waste.” Soon after, he had a vision of impending doom, and warned his monks that barbarians would soon descend upon them and murder all who remained there.

‘His disciples begged the saint to leave with them. But, reflecting on his youth as a thief and a murderer, he replied, “For many years now I have awaited the time when these words spoken by my Master, the Lord Jesus Christ, should be fulfilled, ‘All who take up the sword shall perish by the sword.’” Seven of the brethren remained with St Moses, one of whom hid nearby during the attack. The barbarians slaughtered St Moses and the six monks who were with him.’

I don’t know why, I just love that story. There’s something really moving about Abba Moses stoically, humbly meeting his fate, his death at the hands of the barbarians, believing in his heart that it was his just deserts for his earlier life of sin.

Now, twenty sayings or edifying stories are attributed to Abba Moses in various collections of sayings of the Desert Fathers. My favourite is this one:

‘One day a brother committed a fault and a council was summoned to deal with it. Abba Moses was invited to attend, but refused. They urged him to come, and so he got up to go, but made his point of view about judging others perfectly clear. He took a leaky jug, filled it with some water, and carried it with him. The others came out to meet him, and said to him, “What is this, father?” The old man replied, “My sins run out behind me, and I do not see them, and today I am coming to judge the errors of another.” When they heard that they said no more to the brother, but forgave him.’

After this quick break, we’ll be back to begin St John Cassian’s Conference No. 1, featuring Abba Moses.

St John Cassian’s Conference No. 1 is called On the Goal and End of a Monk. It’s far too long to read all the way through, certainly in a single episode. John Cassian, for all his many virtues, was not exactly concise. He repeats himself a lot. He’s fond of flogging a dead horse, if you like, making his point over and over again. So, I have edited the text—and anyway, we’ll only be covering a part of the text in this episode, about the first third or so.

Now, though St John Cassian presents The Conferences as transcriptions really of conversations he’d had decades earlier with these spiritual men in the desert, scholars believe that that’s not the case and that St John Cassian is presenting his own views on the spiritual life, putting his words into the mouths of the Desert Fathers of Egypt.

That is probably true. But, it’s not a problem for us, because St John Cassian was an absolute master of the spiritual life. As you will see.

So here we go, On the Goal and End of a Monk, Part One.

The desert of Scete is where the most exemplary abbas of the monks dwell, where all perfection is to be found.

Now, I should have pointed out before that this title, Abba—Abba Moses, the abbas of the desert, Abba, A-double-B-A—this title comes from an Aramaic word, Abba, which means ‘father’. There’s something sweet about that title, Abba. It actually means something like ‘daddy’. It’s a very affectionate term. And when you read the lives of the Desert Fathers, right away you see the deep and abiding affection that they have for each other. You realise just how much love flowed between them.

Now, St John says that he’s travelled to the desert of Scete. So, Scete was one of three monastic settlements in the Nitrian Desert, which is a desert on the west side of the Nile Delta not incredibly far away from arable land and civilization, but still by no means, uh, a welcoming environment. Their life was tough. Especially Skete, one of these three monastic settlements. It was the furthest away, it was the roughest.

That’s where St John went, and don’t forget, he didn’t travel alone. With him all along was his best friend, Germanus. They’d travelled to Skete to pick the brains of the most exemplary monks, and St John goes on:

I was eager to consult Abba Moses there, for he had the reputation of being the best-scented flower in that bright garden, virtuous both in deed and in doctrine, and I wished to be grounded in his instruction.

Grounded in his instruction. The Christian way, the Christian spiritual way, must be grounded, and it must be grounded in instruction that is passed down from the Fathers. That’s what Life Sentences is all about. If you’re listening to this, you must have some interest in pursuing a Christian spiritual life. It’s extremely important that that spiritual life be grounded. We’re not just making stuff up, we’re not being led by our own intuitions or—God forbid!—our own emotions. No, our spiritual lives must be grounded in the tradition, in what has been handed down by the Fathers—Fathers like Abba Moses.

St John goes on:

With me was the Holy Father Germanus, with whom I had enjoyed inseparable companionship, from our first training in spiritual combat and onwards, in both the monastery and the desert, and so close was our friendship and so pronounced our shared purpose that everyone declared us to be one mind & soul in two bodies.

One mind & soul in two bodies. That’s just about the loveliest description of spiritual friendship I think you could possibly read. It surely must be a great blessing to have such an intimate friend that you are one mind in two bodies.

St John continues:

Together we implored the holy Abba for an edifying word, and not without tears. For if he were to offer instruction indiscriminately, either to those unwilling or to those lukewarm in their thirst for it, he might appear to incur either the fault of vanity or the charge of betrayal by revealing essential things that ought to be known only to those who desire perfection, to those who are unworthy or receive them with disdain.

Well, let us pay attention to those words, and as we continue on listening to the wisdom of John Cassian and other Fathers in Life Sentences, let us make sure that we are not unworthy and that we do not receive these words with disdain. As St John says, these are essential things that ought to be known only to those who desire perfection. So attend to yourself, as St Basil would say, and find that place in your heart that desires perfection and only then listen carefully to Abba Moses’s words.

St John goes on:

However, worn out by our prayers, Abba Moses began thus. ‘Every art and every discipline,’ he said, ‘has its own skopos, that is to say, its proximate goal, and its own telos, or ultimate end. Anyone who diligently pursues that art sets his gaze on that proximate goal and is gladly willing to endure every labour, danger, and expense for that ultimate end.’

Okay, so this is really the theme of Conference No. 1, the difference between skopos and telos, two Greek words that the dictionary will tell you are basically synonyms. Goal, aim, target, direction, purpose, end. They’re roughly synonymous, but in philosophical and spiritual literature from that time, they had technical meanings. Skopos I’ve translated as ‘proximate goal’, and telos I’ve translated as ‘ultimate end’.

Skopos, proximate goal; and telos, ultimate end. Abba Moses then lays out a rather extended metaphor drawn from farming, which I’ll just summarise. He says that a farmer’s ultimate end, his telos, is a bountiful crop, enough to sell at market and earn a tidy profit. That’s his ultimate end. But, to reach that ultimate end, the farmer’s proximate goal is to ensure that the soil in his field is nutrient-rich, free of rocks, free of brambles, ready for planting. That’s the proximate goal without which he would never achieve the ultimate end of a bountiful crop.

Now, notice: Abba Moses has said that the ultimate end is that for which we are willing to endure every labour. This is your telos. The proximate goal, however, is the thing, Abba Moses says, that we set our gaze on. We focus on the proximate goal, that is our focus. For the farmer, he sets his gaze on that well-tilled, nutrient-rich soil and, focusing on that, he undertakes great labours—ploughing, clearing, fertilising, irrigating, digging—in order to reach his ultimate end.

But Abba Moses is most keen to stress: the most important thing in all of this is to keep your focus NOT on your ultimate end, but on your proximate goal. As we shall see.

Abba Moses continues:

‘Our profession too has its own proximate goal and its own ultimate end, for the sake of which we undertake all endeavours, tirelessly, and even gladly. For its sake, the hunger of fasting does not weary us, the exhaustion of keeping vigil delights us, and continuous reading and pondering on Scripture does not satiate us. We are not deterred by our ceaseless labour, nor by our poverty and deprivation, nor by the terror of this enormous desert.

‘So tell me,’ he said, ‘‘What is your proximate goal, and what is the ultimate end which has brought you to endure all this willingly?’

We answered, ‘We put up with all this for the sake of the Kingdom of Heaven.’

‘Well,’ he replied, ‘as for the ultimate end, you have given a clever answer. But what about the skopos, the proximate goal? You need to know this especially, because by constantly clinging to it, we may be able to attain our ultimate end.’

Cheerfully, we admitted our ignorance, and he continued, ‘As I say, in every art or study there must be first of all a skopos, a proximate goal towards which the spirit points, an aim toward which the mind directs itself unwaveringly. If we fail to discover this, our efforts will be in vain, since those who travel without a route only tire themselves out on the journey without getting anywhere.’

You might be thinking here that Abba Moses is rather belabouring the point, but he’s belabouring the point for a very important reason. It’s easy, in a way, to know what your ultimate end is. Here, in Christian terms, the ultimate end, they’ve said, is the Kingdom of God, the Kingdom of Heaven. How many Christians in their mind think, that’s where I’m headed, I’m headed towards the kingdom of heaven. That’s the ultimate end. But what are they doing to get there? If you just sit around focusing on heaven, imagining that you’re on your way to heaven, is that enough?

No, it’s not enough. Christianity, after all, is not a destination. It is a way. It is The Way. That’s what Christianity was originally called, The Way. So the question is, how do you walk the way? In what way are you to walk?

The how is the skopos, the proximate goal. And Abba Moses is now going to tell us what that is.

St John goes on:

We were puzzled by this, so the old man continued: ‘The ultimate end of our profession is the Kingdom of God, as we said, or the Kingdom of Heaven. Our proximate goal, our skopos, is purity of heart, for without that it is impossible for anyone to reach that ultimate end. If we set our sights in the direction of purity of heart, as if following a sure waymark, we will be safe on our path.’

So, there we have it. The Christian’s ultimate end is the Kingdom of God, but his proximate goal, on which his mind must be always focused, is purity of heart.

We will learn shortly what Abba Moses means by purity of heart, but just remember the words of Christ in the Sermon on the Mount: ‘Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.’ Or the powerful, penitential Psalm 50 where the Prophet David cries out, ‘Create in me a clean heart and renew a right spirit within me.’ Purity of heart, cleanness of heart, this is our proximate goal.

Abba Moses continues:

‘If we let our attention wander a little from purity of heart, we should immediately turn it back to that direction and bring it back again to its proper path. Our efforts must always return to this path, which will recall us if the mind should ever deviate, even slightly, from the route we have adopted.’

As you can perhaps tell, in Abba Moses’s mind, purity of heart is not a state, it is an activity, an activity to be pursued with intention. The mind practises purity of heart. So, when you ponder that beatitude of Christ, ‘Blessed are the pure in heart’, don’t think purity of heart is something that just happens to someone. It’s something someone pursues, actively, diligently. And so, when you pray that Psalm, ‘Create in me a clean heart, O God,’ you’re not asking God to give you something despite your lack of effort; you are asking God to empower your will so that you can pursue purity of heart with effort.

And note: ‘Create in me a clean heart,’ the Psalm says, but then it says, ‘and renew a right spirit within me.’ Purity of heart is linked to a right spirit. And as you’ll see a little later on, Abba Moses himself will relate purity of heart with contemplation—which is what a right spirit is: a spirit, a mind, in accordance with nature, contemplating the Good, contemplating God. And this contemplation is a discipline, it is a practice, it is a free act of the will.

Disciplined, because Abba Moses says that if your attention wanders a little from purity of heart, we should immediately turn it back. And I can say here, one of the great virtues of the tradition of contemplative prayer known as the prayer of the heart, or the Jesus Prayer—’Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, a sinner’ repeated over and over again in the mind, in the heart, with attention—one of the virtues of this tradition is that it is constantly recalling the mind back to purity of heart, to contemplation, as Abba Moses advises. It’s a powerful tool. It’s a powerful contemplative means enabling the mind to remain focused on Christ in the heart.

Abba Moses then goes on to lay out another metaphor, this time not the metaphor of a farmer, but the metaphor, really, of an archery tournament. So he says that at an archery tournament you have archers and they’re firing their arrows at a target, and on the target has been written the reward or the prize that they’ll win if they hit the target. So they’re aiming at the target in order to win the prize. This is another way of distinguishing our proximate goal from our ultimate end. The Christian aims at purity of heart. That’s the goal. That’s what he’s aiming at, purity of heart, in order to win the prize, the ultimate end, the Kingdom of God. And Abba Moses makes it clear, without that target to aim at, the archer would be firing arrows at random, and to no end.

So just as, in order to win the prize you must focus on the target, the Christian must remain focused on the proximate goal, purity of heart, in order to win the Kingdom of God. And Abba Moses now goes on to equate the Kingdom of God with what he calls eternal life.

He says:

‘Now, in the same manner, the ultimate end of our profession is eternal life, as St Paul tells us when he says, “You have your fruit leading to holiness and the end is eternal life.” The proximate goal is purity of heart, which St Paul rightly calls holiness, and without it we cannot attain the aforementioned ultimate end. The same holy apostle speaks elsewhere about this proximate goal and even calls it by the name skopos, saying, “Forgetting the things that are behind, but reaching out to what is ahead, I press on toward the goal, the skopos, for the prize of the upward calling of God.” It is as if he had said, by means of this proximate goal, i.e. purity of heart, I forget what lies behind me, the vices of my former life, and strive towards the heavenly prize, which is my ultimate end.’

So, Abba Moses, St John Cassian here, is creating a complex of different technical terms, spinning a web of interconnected terms to speak in a nuanced, detailed way about the spiritual life.

Our telos, our ultimate end, is the Kingdom of God, which is eternal life, which is the upward calling of God. To reach that ultimate end, we practise our skopos, our proximate goal, which is purity of heart, which is holiness, putting vice and sin behind us and turning towards virtue, striving, struggling, willing to sacrifice for that heavenly prize, for that ultimate end.

As Abba Moses goes on:

‘For this reason, whatever can direct us toward this proximate goal, which is purity of heart, we should pursue with all our strength, but whatever draws us away from it should be shunned like a plague. This is the motive for everything we do and undergo. If we did not have purity of heart continually before our eyes, our efforts would be utterly futile and inconsistent, vainly expended, without any result, and we would also find that our thoughts wandered and were confused. When the mind lacks an abiding sense of direction, inevitably it is distracted in varied ways, moment by moment, and external circumstances are continually pulling it back to the condition in which it had been before.’

Abba Moses is certainly not beating around the bush. The Christian life is one intensely focused upon purity of heart, upon holiness, upon rejecting vice and embracing virtue. This should be continually before our eyes, he says, and what’s more, he says that without it, our efforts, as he puts it, would be futile and inconsistent. Our ‘efforts’, by which he means the day-to-day practices that sort of underpin our spiritual lives: fasting, prayer, reading the Bible, going to church, attending the services, practising charity, giving alms, trying in general to follow Christ’s commandments, to be a loving person, a kindhearted person, all the practical everyday things that we do in the course of our spiritual lives.

If we do them without focusing on purity of heart as the goal, then he says all of those practices would be futile and inconsistent. We would be easily distracted. We might practise them sometimes, but not all the time. We might suddenly forget why we’re doing them at all. And ultimately, he says, external circumstances would pull us back to the condition we were in before, that is to say our vicious condition, our passionate condition, our blind pursuit of pleasure-seeking.

So, purity of heart must be at the forefront of our minds: without that intention as our proximate goal we cannot reach our ultimate end.

And after this short break, Abba Moses will take us deeper into the mystery of purity of heart, revealing how that all-important proximate goal, when pursued with diligence, gives rise to two divine energies of soul: theoria and agape: contemplation and dispassionate love.

Okay we’re back. Abba Moses is now going to introduce us to a sad fellow, really, a monk who has lost sight of his proximate goal.

He says:

‘Now that is why it can happen that men who have renounced enormous wealth in this world, not just large sums in gold and silver, but even great estates, may later on fly into a passion over a pencil. Had they kept their hearts pure in contemplation, they would never have permitted themselves this passion over such trivial things, after abandoning great and valuable possessions in order not to be disturbed by them.’

That is quite a funny image there of a formerly very rich man giving away all of his possessions, moving to the desert, becoming a hermit, and having a conniption fit because someone wants to borrow his pencil. Abba Moses says, had this man kept his heart pure in contemplation, he would never have permitted himself this passion.

Here we see that link between purity of heart and contemplation. Your proximate goal, your immediate focus, is purity of heart, which is the practice of contemplation. You attain purity of heart through contemplation, and you maintain purity of heart through contemplation.

But what is this contemplation? It’s easy to say the word but what does it mean?

The Greek word translated contemplation, the Greek word is theoria. It was translated into Latin as contemplatio, and thus into English as contemplation. It is also the Greek word that gives us the English word theory, a theory, like a theoretical construct in your mind. So the first thing to point out is that theoria, in this sense of contemplation, has nothing to do with our English word theory. Especially because theoria is not theoretical, it is practical. Theoria, contemplation, is a practice.

Which goes back to what I was saying earlier. Christianity is a practice. Faith is a practice of the mind. Faith is the mind’s active trusting in Christ’s Way, trusting in the Way by following the Way, putting the Way into practice. Faith begins when conceptual or theoretical understanding ends and the mind takes that leap in the dark, a leap of faith towards Christ in contemplation of him.

That might sound extremely weird to you, but you must give it a go, you must begin contemplating Christ by turning to him in faith, by attending to his holy name in faith, by emptying the mind of distracting thoughts and filling it with his name only, of attending to your heart, to the movements of your heart, restraining the heart’s passions, and instead directing all your love, all your desire towards God, towards Christ in contemplation. It’s an activity, it’s a practice.

And if you maintain that practice in good conscience, Abba Moses says, you will not find yourself flying into a rage over a trivial passion. You might at the beginning stages (which can last a long time), in the beginning you might feel that rage in your heart, but if you’re mind is fixed on purity of heart, in contemplation, seeing that passion, seeing that rage, suffering that passion, suffering that painful, passionate vision of the rage in your heart, turning to Christ in faith, you would simply suffer the passion silently, without manifesting it, without acting out that rage, without expressing it—certainly not over something trivial like a pencil.

And now Abba Moses will add another dimension to his teaching on purity of heart. He says:

‘This makes it clear that perfection does not consist merely in poverty and the renunciation of all property or in the rejection of rank, without the true possession of that agape which consists essentially in purity of heart.’

You can see, Abba Moses is drawing a sort of Venn diagram, in which all things converge on purity of heart, and now he’s added another circle: agape.

I am using the Greek word agape. It is translated most often these days as love, sometimes as charity, coming from the Latin equivalent of agape, caritas. But I’m going to use the word agape in this text to help you keep in mind that what is being referred to by the word agape is not really what we normally mean by love. Agape is nothing like intense, overwhelming, passionate love. Quite the contrary. Agape is dispassionate love.

In our modern world, the idea of dispassionate love strikes us almost as unintelligible. How can love not be passionate?

Well, there is a kind of love, the truest form of love, agape, that is dispassionate. In the Bible, it is written, God is agape. It is also written that God is Father. And so agape is often described as fatherly love. And if you think about it, fatherly love at its best is dispassionate.

A perfect father would love without any passion, without any selfish interest. A perfect father would love in a way that was totally committed to the good of the child that he loved, calmly committed to that child, loving him or her without demanding anything for himself in return.

If you think about passionate love—erotic, passionate love, of the kind that our modern society tends to valorize above all—it is, to some extent at least, inescapably self-interested. When you fall in passionate love with someone, you want something from them. It could be their body. You may wish to have their body. It may be their attention. You may wish to attract their attention. It may be their esteem. You may wish to win their esteem, or their affection, to suit yourself, to satisfy something in yourself, to derive some kind of pleasure, some kind of satisfaction, for yourself. That’s passionate love—and that kind of love is not divine.

Agape, on the other hand, is dispassionate love, and certainly, for that reason, compared to the intensity of falling desperately, romantically in love, agape can feel very calm. Agape can feel dutiful even. Agape may have very little emotional feeling at all. In fact, I would wager, ideally, it would have no emotional feeling. It would be attended by no emotions. It would be dispassionate. It would be contemplative. It would be spiritual.

But I can also tell you that in the midst of that mode of loving, there can be, equally dispassionately, a tremendous and profound indwelling, upswelling, ego-shattering, death-defying love for God and for everyone else, compared to which, ordinary romantic love is but a shadow.

But that’s a topic for another time. For now, Abba Moses is talking about agape, which he says consists essentially in purity of heart. And he goes on, and he’s about to quote the Apostle Paul:

‘For what does it mean to say, “Agape does not envy, does not act dishonestly, is not arrogant, is not self-seeking, does not insist on its own way, is not easily angered, and keeps no record of wrongs” and so on, except that we should offer to God a heart of perfect purity and keep ourselves untouched by all anxieties.

‘Everything we do and everything we seek should be for this purpose. This is why we pursue solitude. This is why we fast, keep vigil, practise manual labour, and embrace bodily hardship, reading, and all other virtues: so that we may be able to render our heart free from harmful passions and preserve it so, and ascend to the summit of agape by using these practices as steps.’

And he means by ‘practices’ there the things that he enumerated. Solitude, fasting, keeping vigil, manual labour, embracing bodily hardship, deprivation, poverty, reading the Scriptures, reading the Church Fathers, and all other virtues. So, he’s saying that these practices are steps that help us ascend to the summit of agape, which he has equated with purity of heart, which is the proximate goal that will guide us to our ultimate end, the Kingdom of God, the Kingdom of Heaven, eternal life.

Those everyday practices, however, are just steps, just steps along the way. The way is purity of heart, disciplined contemplation cultivating agape, dispassionate love.

And Abba Moses continues:

‘It can happen that some genuine necessity prevents us from performing our ascetic exercises and we fall into gloom, anger, and frustration for the sake of these exercises—even though these very practices were designed to prevent this. The profit we gain by fasting is not as great as the loss we suffer through anger, the profit from reading less than the damage incurred by the contempt of a brother. All these secondary things—that is to say fasting, keeping vigil, psalmody, meditation on Scripture—all of them are properly used by us for the sake of our principal skopos or goal, namely purity of heart or agape. So we must not damage our chief virtue for the sake of these lesser ones. If our proximate goal, purity of heart, remains whole and entire within us, we shall suffer no loss if we are obliged to omit some of these secondary things. But if we lack what we have identified as the principal skopos, for the sake of which we practise everything else, then performing them all, even if we do so perfectly, would be fruitless.’

This is extremely important wisdom. Abba Moses is making it clear that what he calls ‘secondary things’, all the ascetic practices that the spiritual life entails—and indeed it entails them!—all of those secondary things are worthless if, carrying them out, you have forgotten purity of heart.

And he’s saying that one test of whether or not you are pursuing them with purity of heart is how you feel when, for whatever reason, you can’t pursue them. Something happens and you can’t fast on a fasting day. Something happens and instead of saying your prayers at 3 a.m., you have to say them at 6 a.m. You’re sitting down to read the Bible and the phone rings and it’s your mother and she wants to talk to you. How do you react when things like that happen? When you are obliged to relax or even omit one of your ascetical disciplines. Do you get angry? Do you feel frustration? Do you feel sad even, he says? Do you fall into gloom? If that’s the case, then you have been pursuing these ascetical practices for their own sake and not for purity of heart.

It’s a good litmus test. A test of your true intention. Have you maintained the true proximate goal in mind? Or have you been bewitched? Confused? Have you lost sight of the true goal and instead adopted those secondary things as your goal? That would be an error.

And therefore, purity of heart is not equivalent to the ascetic practices, nor to the state of not sinning in action. Those are all secondary things which we practise for the sake of the primary goal, purity of heart, which is no passion in the heart. Purity of heart is not simply not sinning. That might be purity of the flesh, purity even of the mind perhaps. Purity of heart is no passion in the heart. Purity of heart is when, provoked in some way, you feel no anger, no frustration, no sadness. So long as those are in your heart, you have not achieved purity of heart. And no matter if you have not committed any sins, and therefore even if a whole day has gone past and you haven’t committed a single sin and you’ve fulfilled every one of your ascetical exercises perfectly, if there’s passion in your heart, don’t relax, because you have not yet attained the goal. So we must pursue purity of heart.

Abba Moses goes on:

‘You do not acquire all the equipment for some craft and polish it up eagerly, simply to own it without using it. The benefit to be expected from it does not lie simply in the mere possession of the equipment, but in order to gain effectively the skill and the produce of that craft to which the equipment pertains.

‘In the same way, perfection does not lie in fasting, keeping vigil, meditation on Scripture, poverty, and the renunciation of all property, but these are tools to perfection. The ultimate end of our discipline does not lie in those things, but through them we may come to that ultimate end.

‘The exercises would be performed in vain by someone who is content with them as if they were the final good and directed his heart exclusively to them rather than putting all his efforts into them for the sake of the true end to be achieved by practising them. He would indeed possess the equipment of our discipline but be ignorant of the ultimate end for which alone it is effective.

‘Anything at all which might disturb the purity of the mind or its tranquillity should be shunned as an evil, no matter how useful or necessary it seems. That is how we can discern how to avoid all tendencies to error and dissipation and reach the end we desire following a sure path.’

Two things to point out. First, the equipment is necessary. We do need to use these tools of ascetical practices and the virtues, in order to attain purity of heart. If you go back to the farmer metaphor, a farmer has to wake up early, has to dig, to turn over the soil, find the rocks, remove the rocks, find the roots, remove the roots, work the soil, beat the soil, irrigate the soil, turn the soil, plough the soil, again and again, over and over, day by day, season by season, year by year. The farmer must do those things. But he must do those things only with the goal in mind, which is preparing the soil for sowing. If he were to just do those things for themselves without keeping in mind the point of doing them, which is to sow his seed so that from the seed might come a bountiful crop, then he would be a fool. He might as well not be doing those things.

Similarly, if you fast and go to church and pray and all the rest without keeping at the forefront of your mind purity of heart and contemplation— which is in fact the sowing of spiritual seed in the fertile soil of the heart, in the soil of the heart rendered fertile, rendered fertile by the ascetical practices—unless you’re doing those practices with that contemplation and purity of heart in mind, they are worthless. But you still must do the practices!

That’s the first thing to point out.

The other thing to point out is that he says anything at all which might disturb the purity of the mind or its tranquillity should be shunned as an evil, no matter how useful or necessary it seems. This takes great discernment, of course, but clearly what he has in mind here is that whenever you feel, in defence of your ascetical practice, or in defence of your own virtue, whenever you feel passion rising in the soul—sadness, frustration or anger—whenever you feel passion rising in defence of your ascetical practice, defending your self-image as someone who performs ascetical practices perfectly, who practises virtue conscientiously—whenever you feel those passions, then you must not perform the ascetical practice and instead attend cheerfully to whatever it is that has intervened or arisen or come between you and your ascetical practice.

This an absolutely vital part of the spiritual life, learning this discernment, attending to your heart: are you defending your own practice of asceticism with anger or sadness or frustration? Those intervening occasions arise precisely so that we would lay down our ascetical practices, crush that inner ego image, that self-image that says ‘I am someone who performs ascetical practices perfectly’, and instead attend cheerfully to whatever it is that needs attending to.

Now that is by no means licence to just dispense with your ascetical practices, not at all. They are necessary, but they are not the proximate goal, nor are they the ultimate end. The proximate goal is purity of heart, and that must be defended. And you defend it not with rage, not with sadness, not with frustration, but with true agape, dispassionate love.

So yes, Abba Moses has said that anything that will disturb purity of mind must be shunned as an evil. And he goes on:

‘A parable of this state of mind can be found in the Gospels, beautifully demonstrated in Martha and Mary.’

Now, I’m sure you know this, but if you don’t, go to Luke chapter 10 in your Bible and read the story of Martha and Mary. It’s an extremely important story. It features in a lot of Christian spiritual literature. In fact, in the monasteries, it’s one of the Gospel passages most frequently read out in church. The monks love this story, they need this story, as Abba Moses will now reveal.

He says:

‘Martha was busy performing a holy and useful service, waiting on our Lord himself and his disciples. Mary was only intent on spiritual teaching, sitting at the feet of Jesus, which she had kissed and anointed with ointment during her holy confession. Yet it was she whom the Lord commended. For when Martha was hard at work, distracted by her loving care for the provisions, she saw that she could not accomplish such a large task by herself, and she begged our Lord for her sister’s help, saying, “Don’t you care that my sister has left me to serve alone? Tell her to help me.” She was not asking her to do something disreputable, but a praiseworthy service. But what does Martha hear from our Lord? “Martha, Martha, you are anxious and troubled about many things, but few things are needed, or indeed only one. Mary has chosen what is better and it will not be taken away from her.”’

Abba Moses is going to explain what all of that means, but I just want to say that you may have noticed that the version of the story there is slightly different, different from what you’re probably used to. Usually, the words of our Lord there are translated, ‘Martha, Martha, you are anxious and troubled about many things, but only one thing is necessary’, or ‘only one thing is needful’. That’s how it usually appears in our Bibles, not as it appears here: ‘Martha, Martha, you are anxious and troubled about many things, but few things are needed, or indeed only one.’

Interestingly enough, that version of this verse is attested in the more ancient manuscripts and is by far the version that appears most often in the works of the Holy Fathers.: ‘few things are needed—or indeed only one.’

I just wanted to point out that perhaps unexpected reading there, because Abba Moses is going to comment on it.

He goes on:

‘You see that our Lord considered the chief good to be theoria alone, that is divine contemplation.’

That’s Abba Moses’ first takeaway from the story of Mary and Martha, unequivocally that the chief good of the soul, the primary aim towards which the soul should be directed, the proximate goal on which the soul should focus, is theoria alone, divine contemplation, i.e. purity of heart, agape, dispassionate love of Christ, contemplation of Christ.

Abba Moses goes on:

‘We can therefore see that other virtues, no matter how necessary and useful we deem them, are to be placed in the second rank, for they are all subservient to this one. When our Lord says, “You are anxious and troubled about many things, but few things are needed, or indeed only one,” he places the supreme good not in actual good works, however praiseworthy and profitable, but in the contemplation of himself, which is simple and one. When he says “few things are needed” for perfect bliss, he means that our gaze is, firstly, fixed on the careful reflection upon a few holy men, and then one who is already proficient in this contemplation progresses, with God’s help, to the vision of what he calls the One, that is, the vision of God alone. He passes beyond the deeds and wonderful service of holy men to feed on the beauty and wisdom of God alone.’

So that is how Abba Moses interprets that unexpected reading, ‘few things are needed or indeed only one’. He is stating here very clearly that our practice of contemplation involves something like two stages. First, a contemplation of the few, which then progresses to contemplation of the One. He specifies here what are ‘the few’ that we are to contemplate in that first stage of contemplation: a few holy men, he says, their deeds and wonderful service.

Now, the Church does offer the daily commemoration of saints, what is in Greek called the Synaxarion. Every day is dedicated to the commemoration of its own saints. And in the Orthodox Church’s cycle of daily divine offices, during the office of Matins, usually, not always, but usually after the chanting of the sixth ode of the Canon, that day’s entry in the Synaxarion is read out. The lives of that day’s saints are read out and given over to the mind for contemplation.

What are we contemplating in these saints’ lives? We are contemplating their virtues. The saints are contemplative models of the virtues, virtues which are in fact the human manifestation of the divine life, divine energies, divine operations, divine names. So, the mind contemplating the virtues in the saints is raised to contemplating the virtues as they are in the divine, and from there is raised to contemplation of the One, of God himself.

This may help to anchor, or at least provide some metaphysical, if you like, explanation for the fact that the Church’s spiritual life is saturated with the saints and their lives. If you walk into a church, especially an old church, you’ll see on the walls frescoes—covered, the walls covered with frescoes of saints—often in little square boxes, each box filled with the image of a saint, and usually a saint being martyred. The martyrdom of the saints is always being presented to our minds as Christians for contemplation. We are contemplating the martyrdom of the saints, invoking that martyrdom, invoking that saint’s name, praising and hymning that saint’s martyrdom.

But of course, the saint’s martyrdom is a participation in Christ’s own crucifixion, in his martyrdom, which in itself is a manifestation on the level of history and time of a heavenly reality: Christ, a man on earth crucified on the Cross, is also the lamb on the throne of God in Heaven slain from the foundation of the world.

So you see this cascading contemplation from the lives of the saints, modelling the virtues, to the way in which those virtues inhere pre-eminently in Christ, both incarnate as Jesus of Nazareth and now ascended into Heaven, radiantly enthroned there—a cascading, elevating contemplation, directing the mind upwards, upwards, upwards, ever more towards the one God.

That’s just my initial attempt there to make a little bit of sense at least of this question of theoria, of contemplation, of what it is, of how it is done in the Church. In the next episode of Life Sentences, Abba Moses will speak more about contemplation and we will learn more and more and more about it as we continue our journey through the Church Fathers.

For now it is enough to finish this first part of St John Cassian’s Conference No. 1 with Abba Moses continuing:

‘Mary therefore has chosen what is better and it will not be taken away from her. We must observe this carefully. When he says Mary has chosen what is better, he may well be silent about Martha, and certainly does not appear to rebuke her, but in praising the one he does imply that the other is inferior. And when he says it will not be taken away from her, he shows that the ministry of the other one can be taken away. Physical good works cannot really endure in a man, but he shows us that Mary’s devotion can never be brought to an end.’

That’s where we’re going to end this episode of Life Sentences. Abba Moses has explained to us, in the spiritual life we must pursue all of the virtues with one goal in mind, purity of heart, eagerly willing to sacrifice everything and to struggle for the Kingdom of God, which is our ultimate end.

Purity of heart, he says, gives rise to contemplation, and contemplation maintains purity of heart.

Purity of heart and contemplation generate agape, dispassionate love in the heart, in the soul, all of this together, practised diligently, with one’s hope always on the ultimate end, on God and on his kingdom.

Everything else is secondary and indeed, he says, will pass away. These secondary things, though necessary, cannot really endure, so why allow yourself to get upset whenever, for whatever reason, you cannot carry them out?

The secondary things, all those practices, will end. But purity of heart in contemplation generating agape will never end, and therefore should never end, not even now, in this life.

We must maintain purity of heart. You’ve got the point.

In the next episode we will continue hearing Abba Moses’s ideas. He has a lot of ideas about the afterlife, about the condition of the soul after death, and he takes us even more deeply into what contemplation is, enumerating some of its various modes.

So, stay tuned for that.

Thank you very much for listening to this episode of Life Sentences. I really can’t stress that enough. These episodes are for me as much as they are for you, whoever you are. I learn so much preparing the texts, reading through the texts, thinking about the texts, which helps me to remain committed to that proximate goal of contemplation and purity of heart.

If Life Sentences is helping you to maintain your focus on your proper proximate goal, then please consider taking out a paid subscription. I really do need the support. If you’ve taken out a paid subscription, once again, thank you very much. I appreciate it more than I could ever tell you.

That’s it for this episode of Life Sentences. Stay well.

Share this post