What follows is a complete transcript of this week’s podcast episode, which you can listen to in the Substack app or via your preferred podcast platform.

The podcast is designed to be listened to, so I encourage you to listen. But I’m also providing transcripts, as you may want to read along as you listen.

Welcome to Life Sentences, an exploration into the wisdom of the ancient Church Fathers, presented by me, Thomas Small.

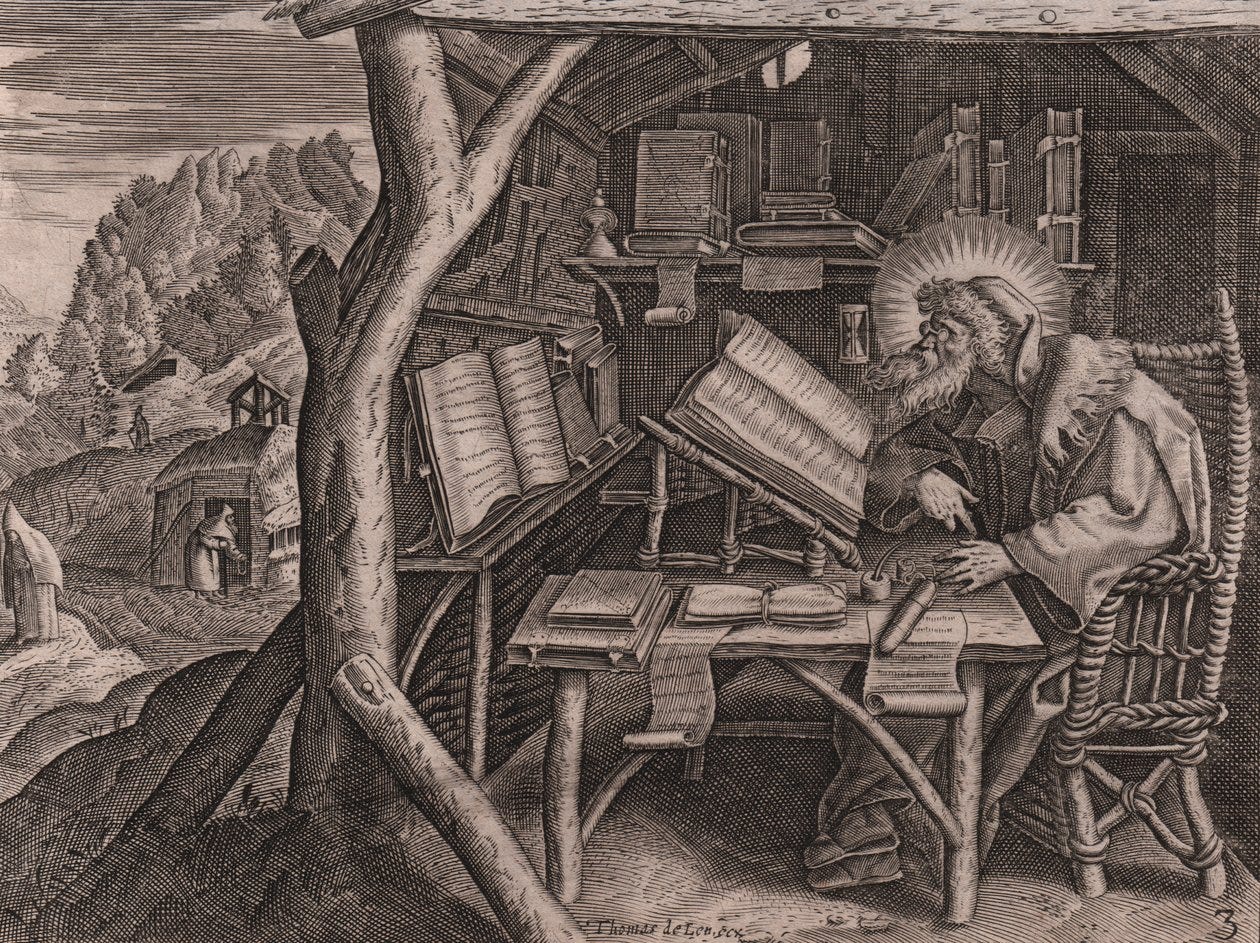

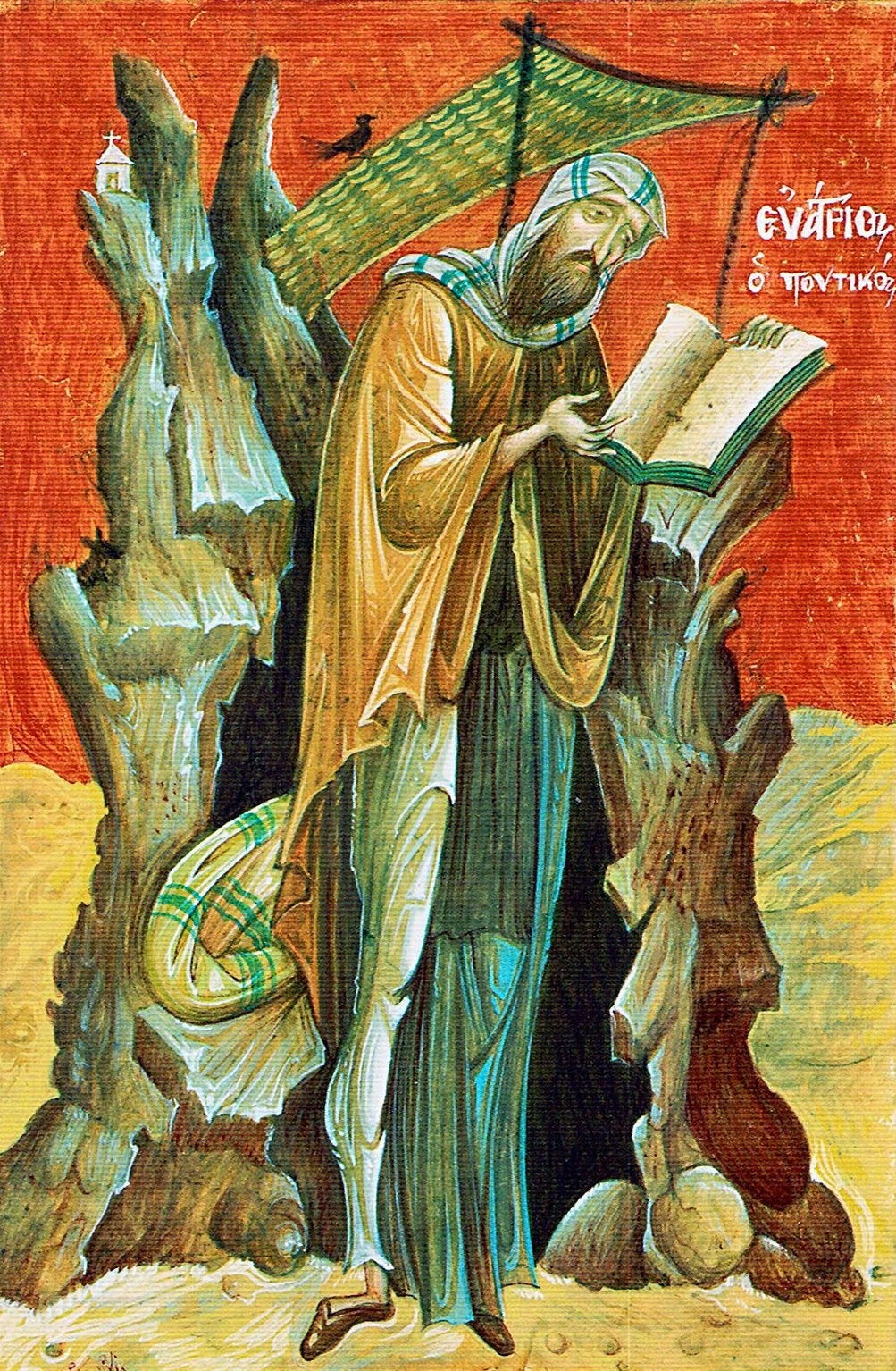

In this episode, we meet John Cassian’s teacher, Evagrius Ponticus, whose penetrating intellectual vision illuminates the narrow path to purity of heart, and who provides us a detailed analysis of the three stages of the spiritual life.

Right, last time John Cassian and Germanus said goodbye to Abba Moses the Black. Abba Moses’ long discourse on purity of heart climaxed in a description of contemplation in its many modes, and he explained in greater detail where our thoughts come from and how we’re meant to allow only divine thoughts to penetrate our minds so that only the thoughts that come from God are sown into the soil of our heart, which we make fertile and ready for planting by constantly ploughing our hearts with metanoia, repentance, inner attentiveness, detachment, self-sacrifice — that is to say, by walking the Way of the Cross.

Taking his leave of Abba Moses, John Cassian then moves on to other Desert Fathers, his conversations with whom he later wrote up in his classic work, The Conferences. I had meant for us to move on to another one of those conferences, but while preparing this episode I changed my mind. For in real life, John Cassian, having finally arrived at the monastic community of Scetis, settled down there for over ten years, joining a fellowship of monks at whose centre lay a controversial spiritual genius whose writings on the spiritual life remain foundational to this day: Evagrius Ponticus.

I mentioned Evagrius last time, teasing the controversy that continues to swirl around his name. And as I say, my plan was to stay with John Cassian. But then I thought, why not do what Cassian did and spend a few episodes sitting at the feet of Evagrius himself and learning directly from him? So that is what we shall do.

Especially as, in the words of Archbishop Alexander Golitzin, who is also a monk of Mount Athos, Evagrius was ‘the greatest theoretician of the ascetic life, whom everyone who followed him read with great profit.’

But first, who was Evagrius?

As his name suggests, he was from Pontus. That’s the region along the southern coast of the Black Sea in what is now northeastern Turkey. We’ve been to Pontus already on Life Sentences, because it was also the birthplace of St Basil the Great, who will play a big role in Evagrius’s story.

Evagrius was fifteen years younger than Basil. He was born around the year AD 345 in the small town of Ibora, called İverönü today, and he was born into a Christian family. His father was a chorepiskopos, that is, a countryside bishop who ministered to rural villages in the name of the more senior metropolitan bishop. So Evagrius grew up deeply rooted in the faith.

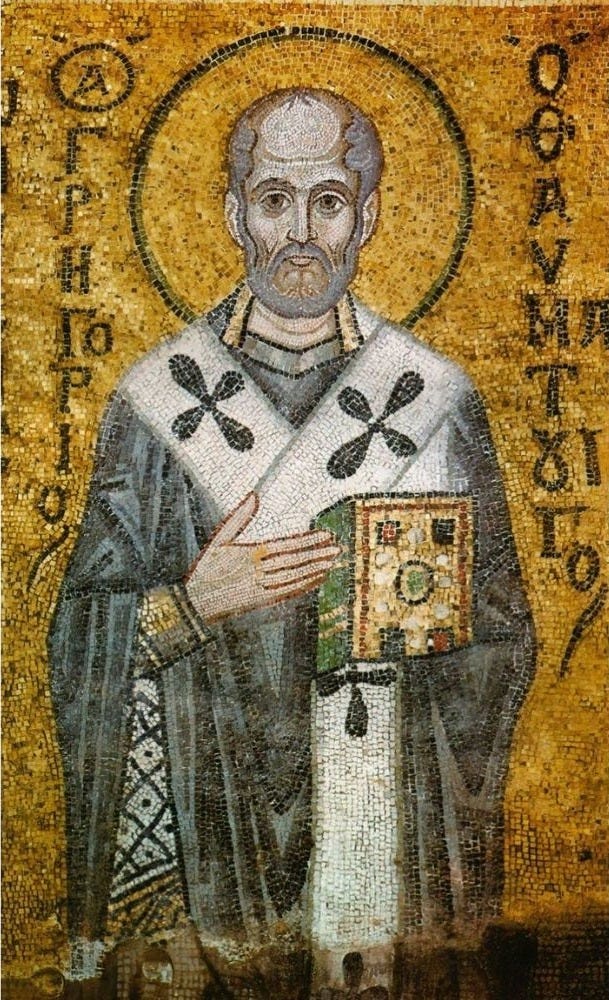

Now, you’ll remember from last time that Evagrius and his circle in Scetis were devotees of the great, if notorious, third-century theologian Origen of Alexandria. Well, Origen’s influence on Evagrius would have started from the very beginning of his life. Because, you see, Evagrius’s hometown of Ibora was only twenty-five miles from the much larger city of Neocaesarea, today known as Niksar. And a hundred years earlier, the bishop of Neocaesarea was St Gregory the Wonderworker, who was a pupil of Origen himself.

So we’ve jumped back in time a hundred years, to the mid-third century. This St Gregory the Wonderworker began life as a wealthy pagan who left Pontus to study law in Beirut. During his time there, he traveled to Palestine to visit his brother and he encountered Origen, who was living in Palestine at the time. Gregory was instantly attracted to the brilliant catechist, who was a forceful preacher and possessed a penetrating intellect. And Origen was also clearly impressed by what he saw in Gregory. ‘Your natural ability,’ Origen wrote to Gregory in a letter that still survives, ‘enables you to become an accomplished Roman lawyer or a Greek philosopher of one of the reputable schools. Nonetheless, I have desired that with all your power you would apply yourself ultimately to Christianity.’

Yes, Origen had targeted the young law student for conversion. But in Origen’s mind, becoming a Christian did not mean you had to reject the wisdom that could be found in Greek philosophy. In fact, the opposite.

‘I have prayed,’ Origen went on, ‘that you would accept effectively those things from the philosophy of the Greeks that can serve as a general education or introduction for Christianity, and those things from geometry and astronomy that are useful for the interpretation of the holy scriptures.’ Origen believed that just as elementary disciplines like mathematics, grammar, and logic prepare the mind for philosophy, so philosophy can prepare the mind for Christianity. ‘And indeed,’ he continued, ‘scripture hints at this principle in Exodus, where God tells the children of Israel to ask their Egyptian neighbours for vessels of silver and gold and for clothing. Having in this way despoiled the Egyptians, they may find material among the things they have received for the preparation of divine worship.’ Origen there is referring to the Israelites escape from slavery in Egypt, when according to the story, they left with as much of Egypt’s wealth as they could lay their hands on.

This idea of ‘despoiling the Egyptians’ — the idea that pagan philosophy could be carefully transmuted into Christian wisdom by a man of intelligence and discernment — this idea convinced Gregory to become a Christian. He was baptised and became one of Origen’s closest and most ardent disciples. For seven years, Origen guided Gregory’s moral, ascetic, and intellectual formation. And then Gregory returned home to Pontus, where he soon became its bishop. When he arrived home, there were only seventeen Christians in the whole area. But it is said that such was his success as an evangelist that when he died thirty years later there were only seventeen pagans.

So, this is the church that Evagrius grew up in one hundred years later. The church in which his father was a bishop. The church founded by Origen’s disciple, St Gregory the Wonderworker. And clearly St Gregory’s brand of Christianity had taken root in Pontus, a Christianity that felt free to absorb what was worthwhile and true in Greek philosophy. We already saw this in our episodes on St Basil, who also grew up in a wealthy Christian family, and also received a fine classical education, as did his sister Macrina and his brother Gregory of Nyssa. Evagrius was no different.

In fact, you’ll remember that St Basil studied in Athens where he met St Gregory of Nazianzus. (Sorry, that’s the third St Gregory in this episode so far. There were a lot of Gregories around.) You’ll also remember that when he returned to Pontus, St Basil opened a small monastic retreat where he began to pursue Christian philosophy. Well, that retreat was very close to Evagrius’s hometown, and when Evagrius was about fifteen years old, Basil’s friend Gregory came to that retreat, and together he and Basil compiled an anthology of Origen’s writing known as the Philokalia, the ‘Love of the Beautiful’. Evagrius was certainly around. Gregory wrote a letter praising the young man’s eloquence, and a decade later, when Evagrius was twenty-five, he traveled to Cappadocia where St Basil was now bishop and joined his philosophical circle there.

Basil soon ordained Evagrius as a reader, i.e. someone authorised to read the Epistle in the divine liturgy, to chant, and to teach the catechumens. So when Basil died in AD 379 when Evagrius was thirty-four years old, Evagrius had been receiving Christian instruction from him on and off for twenty years. Evagrius was clearly a spiritual son of St Basil the Great.

As he lay on his deathbed, St Basil had received a messenger from the Emperor Theodosius, asking him to recommend someone who could combat the heresy of Arianism which was rife in Constantinople. With his dying breath, St Basil said there was no one better to take up that challenge than his old friend, St Gregory of Nazianzus, who was promptly called to Constantinople — and who, don’t forget, Evagrius had known as a precocious fifteen-year-old. So now, having lost one spiritual father, Evagrius gained another, St Gregory. He left Cappadocia and moved to Constantinople, where St Gregory greeted him warmly and enthusiastically invited him to join his theological enterprise. Before long, St Gregory had ordained Evagrius a deacon.

That’s where we’re going to leave Evagrius for now, in Constantinople, newly ordained a deacon and acting as St Gregory’s right-hand man. You’ll notice I stressed two things about his life so far: that he was raised in the church and that he received a good classical education as was the norm for the Cappadocian tradition. This matters because we’ll see in later episodes, Evagrius’s theology got into hot water with the Church and so many people are surprised to find just how Christian his upbringing was and how close he was throughout his life to great saints like Basil and Gregory.

And also because many people still look on the Christian appropriation of Greek philosophy with suspicion. And yet, as we’ve seen, philosophy was not in itself considered a bad thing in the early centuries of the Church. Far from it.

Okay, this introduction has been long enough. Here we go, Life Sentences’ first text by Evagrius Ponticus, The Praktikos.

In fact, I lied. We’re not going to move on immediately to The Praktikos. Instead, I wanted to start with an excerpt from the first — which is to say the earliest — writing by Evagrius that has come down to us, a letter that he wrote to Cappadocia from Constantinople, probably after he’d become a deacon there.

For many, many centuries, this letter circulated under the name of St Basil, but modern scholarship has determined beyond any shadow of a doubt that it was in fact written by Evagrius. And we’ll see down the line that a lot of Evagrius’s writings would be transmitted down the centuries under other people’s names, hiding the fact that they were by him because of the unfavourable way that the Church decided to remember him. And yet people couldn’t give up the texts. They were too full of wisdom, as we’ll see.

So this earliest text by Evagrius, this letter that he sent from Constantinople to Cappadocia, is known as On the Faith. And I think it’s a banger. I love it. The main body of the letter addresses the theology of the Holy Trinity, which was the subject of ferocious debate inside Constantinople at the time. That’s why St Gregory had been called there by the emperor, to end all the fighting and clarify the Church’s doctrine. Evagrius’s presentation of Trinitarian dogma in the letter is wholly orthodox, but then he moves on to address some other topics, topics that I think do a good job of grounding Evagrius’s way of thinking and therefore can act as a good introduction to the text we’ll be focusing on over the next few episodes, The Praktikos.

You’ll instantly recognise several themes that we’ve covered already in Life Sentences. Evagrius here is standing in the same tradition as St Leo the Great, St Basil the Great, Abba Moses, and John Cassian, but he expresses the tradition with remarkable and rather unparalleled clarity, as you’ll see.

So yes, we’re beginning with this excerpt from Evagrius Ponticus’s letter On the Faith. He writes:

Let such things as we have said about the venerable and holy Trinity suffice for the moment, for it is not possible now to extend further the discourse about the Trinity. But taking seeds from our humility, cultivate for yourselves ripe corn, since we further require fruit from such things. For I have faith in God that through the purity of your life you will reap thirty, sixty, and a hundredfold. For ‘blessed are the pure of heart, for they shall see God.’

What Evagrius has just said there is remarkably similar to what Abba Moses said in the last episode. He’s laid out the church’s teaching on the Holy Trinity, and then he characterises that teaching as seeds which are to be planted, he says, and cultivated in the heart, ripening into corn and bearing fruit. And this process of planting the seeds of divine thoughts, the Church’s teachings on the Holy Trinity, into the heart and cultivating the seed is linked to purity of life — ascetic practice, the virtues, walking the Way of the Cross — and he finishes by saying that all of that is summarised by that beatitude of Christ that Abba Moses used so often: ‘Blessed are the pure in heart for they shall see God.’ So this is straight out of Abba Moses, straight out of John Cassian, an indication that John Cassian learned from Evagrius.

Evagrius goes on:

And brethren don’t consider the kingdom of heaven to be anything other than true noetic perception of truly existent beings which the holy scriptures call blessedness. For the kingdom of heaven is within you and since the inner man consists of nothing but theoria, the kingdom of heaven must be theoria.

Again, this is very similar to what Abba Moses presented. Yet there is something uniquely Evagrian about this particular passage which I want to point out.

In Evagrius’s theology there’s a difference between the kingdom of heaven and the kingdom of God. Not a sharp and absolute delineation, but nonetheless a difference. This was not the case in John Cassian. John Cassian used ‘kingdom of heaven’ and ‘kingdom of God’ interchangeably. Evagrius does not do this. The kingdom of heaven Evagrius equates with theoria, contemplation, as you’ve just seen. And to that end, he would agree with Abba Moses about everything Abba Moses said, that purity of heart, which is our goal, generates contemplation in the heart, that contemplation is linked to agape — and for Evagrius that whole reality, contemplation and love, is the kingdom of heaven. The kingdom of God is theologia, or theology proper. And about that we’re not going to say anything. It’s far too advanced. But I wanted to point out this difference between the teaching of Evagrius and John Cassian on this particular point. Because John Cassian, equating the kingdom of heaven and the kingdom of God, called both our ultimate end. Because Evagrius distinguishes between kingdom of heaven and kingdom of God, he would be saying that our proximate goal, theoria, purity of heart, is the kingdom of heaven, whereas our ultimate aim is theologia, the kingdom of God, the highest vision of God. Just a distinction there, really in terminology, not in teaching.

He goes on:

For what we now see only as shadows, as in a mirror, later on we shall behold their archetypes, when we have been freed from this earthy body, and have put on an indestructible and immortal body. We shall behold them provided that we steer our lives along the straight path and take care to maintain true faith, for without these things no one shall see the Lord.

Okay, so you see, the teaching here isn’t radically different from what we’ve already seen in Life Sentences, a distinction between the visible and the invisible, or the sense-perceptible and the noetic. This has been the framework throughout. But here, Evagrius is more specific, and when explaining the difference between the sense-perceptible and the noetic, he adopts explicitly Platonic terminology. Now we see in shadows, there we will see the archetypes. That’s very Platonic.

But then in a Christian move he links this transformation of perception from the material to the immaterial to a transformation of the body from an earthy one to an immortal one. This indicates that what people often say about Evagrius’s theology — that it was too Platonic, that it believed that the body was a prison, that the soul needed to escape from this prison, and that the perfect human being would be bodiless, a soul only — is in fact not the case. Evagrius’s theology here is orthodox: this earthy body, this carnal body of flesh and blood, will die and, when resurrected, be changed into something spiritual, as a result of which its powers of perception will be enhanced and it will see directly the archetypes of everything that now with a fleshly body it only sees the shadows of.

And he says clearly, this will only happen if we walk the straight path and maintain true faith. So Evagrius is by no means cavalier about the Church’s teachings. A moral life and obedience to dogmas are required, for he says without them no one shall see the Lord. And let me be clear: in Evagrius’s mind, the goal of our existence is to see God. That’s what we are meant to do, and that’s what we will do, in the end, when we live in blessedness, contemplating God.

He goes on:

And let no one interrupt by saying, ‘Here you are philosophizing with us about incorporeal and entirely immaterial being, while I am ignorant of the things at my feet.’ For I consider it absurd to allow the senses freely to indulge in the material things proper to them, while the nous alone is restrained from its proper activity. For just as sense perception reaches out towards sense-perceptible things, so too does the nous reach out to noetic things.

Now, obviously, this is that dichotomy again between the visible and the invisible, the sense-perceptible and the noetic. But notice what Evagrius is really saying here. He is meeting an objection he expects to get, which would basically dismiss any talk of noetic things in favour of focusing only on sense-perceptible things. Like, ‘Don’t bother me about the noetic things of the faith. I’ll focus only on the sense-perceptible things first, and then when I master them, then we can talk about noetic things.’ Evagrius isn’t having it. He says, no, you are right now an embodied nous. Your body possesses sense perception. This is good, it is to be used wisely. But your nous possesses noetic perception, and it must be activated, it must be energised no less than your body’s sense perception. And in fact, energizing the nous so that it perceives spiritual realities is what Christian worship is all about.

Evagrius goes on:

At the same time this too must be said, that God our Creator made these natural faculties of discernment to operate without needing prior instruction. For no one teaches sight to discern between colours and shapes, nor hearing to discern between noises and voices, nor smelling to discern between odours pleasant and foul, nor taste to discern between sweet juices or savoury broths, nor touch to discern between soft and hard or cold and hot. In the same way, no one teaches the nous to grasp noetic realities.

Okay, how interesting! What Evagrius has just said helps us to understand better what the nous is. The nous, the mind, the intellect, is not something that can be taught. It’s like sight or hearing or taste. Sight just knows how to see. Hearing just knows how to hear. No one teaches sight or hearing how to see or hear. In the same way, no one teaches the nous to perceive noetically. It does so naturally. This means the nous is not our rational, discursive intellect, not that part of ourselves that learns, that goes to school and is trained in thinking. That’s not what the nous is. The nous is a kind of seeing, a natural faculty of discernment, Evagrius has called it, which operates just as naturally as any of the five senses do.

And he goes on:

And just as these bodily senses, when they suffer impairment, need only care and they easily fulfill their proper activity, so too the nous, being joined to the flesh and filled with the mental images arising from it, requires faith and upright conduct, which guide its steps like the feet of a deer and set it upon high places.

Now that’s a remarkable passage. First of all, it shows what a wonderful writer Evagrius was. He really was. He could express so much in so few words.

But also the teaching is so clear. If the nous is, say, like seeing, like sight, and operates naturally, without having to be taught, just like vision does, then the question is, why then can we not see noetically? Why then is our noetic vision, our perception of spiritual realities, so dull? Well, think of your eyesight. When is it dull? When your eyes are closed, when they suffer some impairment, as Evagrius has said here. And what is the impairment of the nous? He makes it clear. The impairment of the nous is being joined to the flesh. Because, joined to the flesh and therefore implicated in the sense perception of the flesh, the nous is filled with mental images, fantasiai in ancient Greek, fantasies, mental images. This is, for the nous, an impairment. The nous wants to see spiritual, invisible reality directly. It doesn’t want mental images to intervene, to get in the way of that vision. And yet, being joined to the flesh, it does.

And so then, what’s the therapy? You might think, based on what people accuse Evagrius of teaching, that he would say you’ve got to get out of the flesh. You’ve got to escape this prison of a fleshly body. But that’s not what he says at all. He says the mind joined to the flesh requires faith and upright conduct, and that this will guide its steps upwards to high places. Faith and upright conduct, precisely as St Leo, as St Basil, and as St John Cassian taught. Our minds are in our bodies of the flesh so that we would learn how to see the invisible by faith. Faith that is made active in our bodies of flesh through upright conduct. The body is not to be discarded or despised, not at all. It is a tool that we use to practice faith so that our hearts are purified, our minds in our hearts see clearly, etc.

So Evagrius’s teaching here is the same as the other Fathers that we’ve covered in Life Sentences. And this teaching is Christianity. It is the inner essence of the Christian faith.

So that’s the end of the excerpt I wanted to read from On the Faith. And so maybe we’ll take another quick break here. You can push pause on the podcast, go make yourself a cup of tea, or just clear your heads, come back to it later.

And when we get back, we will truly begin Evagrius’s foundational text, The Praktikos.

Right, The Praktikos by Evagrius Ponticus.

So this text is the first in a trilogy that Evagrius wrote in which he attempted to sum up his entire teaching. The Praktikos is the first volume in the trilogy, followed by The Gnostikos, the ‘Gnostic’, followed by the Kephalaia Gnostika, the ‘Gnostic Chapters’. As we’ll shortly see, each volume in the trilogy corresponds to a major stage in the spiritual development of the human person, according to Evagrius.

Now, because Evagrius’s theology in the end was condemned by the Church, the second and third volumes of that trilogy, and especially the third, were sidelined. Forgotten. The original Greek text of those volumes was barely copied. They’ve come down to us largely in Syriac, Armenian, or Old Slavonic translations.

The Praktikos, however, was not forgotten in the mainstream of Eastern Christian spirituality. Greek-speaking monks continued to draw on it, although often a different name was attached to the text, because Evagrius’s name became so suspect. Saint Nilus of Ancyra, for example. His name became the standard one to affix to Evagrian texts. But as I say, The Praktikos remained not only read, but fundamental, foundational to Eastern Christian monastic spirituality, either in whole or in excerpts, sometimes slightly rewritten. And I’ll say more about the text as we go on.

For now, you should know that Evagrius wrote in what are called chapters. Most Evagrian texts are divided into what are called chapters. This was a standard genre in the late antique period. Instead of one single text tracing one single argument — like the texts we’ve read on Life Sentences so far by Basil, John Cassian, Leo — Evagrian texts are composed of chapters. Relatively short, sometimes a sentence or two, sometimes a paragraph, maybe two paragraphs, but relatively short pieces of writing communicating a single idea and then strung together chapter by chapter, as they’re called, to make up the text. The Praktikos is comprised of one hundred chapters, and in this episode we will be going through the first five chapters only, which are really an introduction to the text. But this will lay a firm foundation for us moving forward as we read more of Evagrius’s writings.

So here we go, The Praktikos by Evagrius Ponticus, chapter 1:

Christianity is the doctrine of Christ our Saviour, consisting of praktikē, physikē, and theologikē.

Right, you see immediately this first chapter is straight and to the point, but also full of jargon. Evagrius was a rather scientific thinker, and so his writings employ a lot of technical jargon, which we must wrap our heads around if we’re going to understand what he says. And here in this very first chapter are three technical expressions, which I have left untranslated to draw attention to the fact that they are technical terms and and we need to really understand them.

So praktikē, physikē, and theologikē. In Evagrius’s system, the spiritual life consists of three primary phases. The first — which this text, The Praktikos, focuses on — he called praktikē, coming from a Greek word that means ‘to do, to accomplish, or to practice’, and is therefore the first stage of the spiritual life concerned with practical asceticism, moral purification, and the active struggle against the passions. That’s praktikē. And so the name of this text, The Praktikos, could be translated as something like ‘pertaining to action’ or ‘related to practice’. And since here on Life Sentences were all beginners in the spiritual life, this text is particularly useful.

So that’s praktikē, the first stage in the spiritual life according to Evagrius.

The second stage, physikē, from the Greek word physis meaning ‘nature’, is the stage of the contemplation of created reality, the contemplation of all that is natural in the sense of being created, and therefore is basically the stage of theoria, contemplation.

And the third stage is theologikē, theology properly so-called, which is when the mind sees God directly, when the mind goes from the contemplation of God’s creation to the contemplation or the vision of God himself. That’s the third and final stage of the spiritual life according to Evagrius.

This threefold scheme is not dissimilar to Abba Moses’ presentation of the spiritual life in the last text by John Cassian. If you remember, Abba Moses said that the spiritual life consists of indispensable means towards a proximate goal aiming at an ultimate end, which can be translated into Evagrius’s terms: the indispensable means are praktikē: the struggle against the passions, the struggle for virtue, acts of asceticism. The proximate goal is physikē: purity of heart which is contemplation blossoming into dispassionate love, all inclining towards that ultimate end, the kingdom of God, theologikē: the direct vision of the divine in itself.

And notice as well that Evagrius defines Christianity as ‘the dogma of Christ our Saviour’. This has a double meaning. On the one hand, it means Christianity is the teachings of Christ. Christianity follows the teachings of Jesus Christ. But it is also, and I think more specifically, the dogma of Christ our Saviour, the dogma that Jesus Christ is the Messiah, the Saviour of the world. And so these three stages, praktikē, physikē, and theologikē, are simply the working out or the blossoming in the soul of that dogma when faithfully held.

So that’s chapter 1. ‘Christianity is the dogma of Christ our Saviour consisting of praktikē, physikē, and theologikē.’

Chapter 2:

The kingdom of the heavens is dispassion of soul accompanied by true gnosis of beings.

‘The kingdom of the heavens is dispassion of soul accompanied by true gnosis of beings.’ In this second chapter, Evagrius is expanding on the second stage of the spiritual life, physikē, the contemplation of beings. He also calls this stage ‘the kingdom of the heavens.’ You’ll remember that in Evagrius Ponticus’s thought a distinction is drawn between ‘the kingdom of the heavens’ or ‘the kingdom of heaven’ and ‘the kingdom of God’. Both of these expressions are found in the four Gospels and it must be admitted most Church Fathers use them interchangeably — as we do today. Most of us think that ‘the kingdom of heaven’ is a synonym for ‘the kingdom of God’, that they are the same thing. This is not the case in Evagrius’s writings. He makes a distinction. The kingdom of the heavens, for Evagrius, is the stage of physikē, of contemplation. Whereas the kingdom of God is the stage of theologikē, the vision of God Himself.

And he defines the kingdom of the heavens here, or physikē, in two ways. He first says that it is dispassion, in Greek apatheia. I’ve used this word ‘dispassion’ before in Life Sentences to talk about agape, dispassionate love. And it must be stressed that though the Greek word there, apatheia, is where our English word ‘apathy’ comes from, there is nothing apathetic in the emotional sense about dispassion. A dispassionate soul is not a soul that doesn’t care about anything. Quite the contrary. The dispassionate soul is a soul that has liberated itself from the passions, from attachment to sense perception and pleasure-seeking, that the love of God and the love of neighbour, which is natural to the soul, can flow forth unimpeded. So just like in John Cassian, dispassion of soul is agape, and Evagrius says it is accompanied by true gnosis of beings, i.e. theoria — again, just like in John Cassian. Purity of heart, which is John Cassian’s word for apatheia, dispassion, which is agape, dispassionate love, is accompanied in John Cassian by theoria, which Evagrius calls the true gnosis of beings, the knowledge of what beings truly are, created beings. Because you’ve detached from sense perception, the mind can perceive the truth of beings, no longer distracted merely by the appearance of beings or the surface of beings. This is the second stage, physikē, the kingdom of the heavens.

And one final thing to point out is that if the kingdom of the heavens, the second stage, is dispassion of soul, then praktikē, the first stage, is the struggle to reach dispassion by struggling against the passions: pursuing asceticism and all the other indispensable means in order to achieve dispassion of soul.

Right, that’s chapter 2.

Chapter 3:

The kingdom of God is gnosis of the Holy Trinity, coextensive with the structure of the nous and surpassing its incorruptibility.

Right, okay, let’s have that one more time:

The kingdom of God is gnosis of the Holy Trinity, coextensive with the structure of the nous and surpassing its incorruptibility.

I don’t want to say too much about that. That’s a very high stage of the spiritual life, of which I don’t even have the faintest glimpse.

Just to point out that here we see the kingdom of God being for Evagrius a metaphor for knowledge of God himself, the Holy Trinity. This is the ultimate end in John Cassian, which he also called the kingdom of God, and a lot could be said, certainly contemplated, about the second half of that sentence, that this knowledge of the Holy Trinity is both coextensive with the structure of the nous and surpasses the nous’s incorruptibility.

But I won’t say anything about that, apart from suggesting that Evagrius’s understanding of what it is to be made in the image of God is probably being expressed there. The nous is the image of God in us and therefore when the nous is united with its prototype, God, the knowledge of God the Holy Trinity fills the nous completely, and yet the knowledge of the Holy Trinity is never exhausted by the nous, that God as the source of knowledge, the source of blessedness, the source of immortality and incorruptibility, always transcends the mind’s capacity to experience it.

So that’s chapter 3.

Now here in chapter 4, Evagrius is going to lay out some foundational psychological principles, really, that underpin that first stage, praktikē, on which this text, The Praktikos, is primarily focused.

So chapter 4:

Whatever someone loves, he also completely longs for, and whatever he longs for, he also struggles to attain. And whereas desire is the starting point of all pleasure, desire arises out of sense perception, for that which is devoid of sense perception is also free of passion.

One more time:

Whatever someone loves, he also completely longs for, and whatever he longs for, he also struggles to attain. And whereas desire is the starting point of all pleasure, desire arises out of sense perception, for that which is devoid of sense perception is also free of passion.

Okay, quite a complicated set of ideas there. Let’s take it piece by piece.

First of all, he says, ‘whatever someone loves’. And Evagrius there is speaking about eros, erotic love. Not only sexual love. Erotic love understood generally as the love which seeks to unite itself with an other.

This is distinct from agape, the highest form of love, which I’ve called dispassionate love, which isn’t the love that seeks to unite with an other, but is the love which empties itself, the self-sacrificial love — through which that erotic desire is actually achieved. So eros yearns to unite with the other, agape empties the self in order to achieve that union. That’s how the two forms of love, agape and eros, are related.

And of course, ideally, indeed naturally, the nous possesses an eros for God, a desire to unite with God, and achieves that desire by loving God self-sacrificially. That’s the highest, most ideal, most natural way in which eros is experienced and expressed by the human being, in the nous, as a desire to unite with God.

And as Evagrius says here, ‘whatever someone loves or experiences eros towards, he also completely longs for.’ I think that’s clear. And he goes on, ‘and whatever he longs for he also struggles to attain.’ So having established one principle, that of eros, which yearns for an object, Evagrius introduces an accompanying principle, the principle of struggling to attain what you long for. And just as, ideally, eros is a noetic power moving the mind, the nous, to unite with God, so is this struggle ideally the nous’s struggle against anything that would dilute or misdirect that erotic longing for God.

Now that’s ideally. That’s when the nous and therefore the whole human person is operating in accordance with nature, in accordance with its nature as the image of God. Although Evagrius hasn’t explicitly made this first sentence about what is ideal, he said whatever someone loves he also longs for, etc. So this chapter 4 is establishing a general principle about the human mind. The human mind loves erotically, longs for the object of that erotic attraction, and will struggle to attain it. Now that’s true whether that object is God or that object is something created. And the second sentence of this fourth chapter is now going to describe the further dynamic when that object is created. He said, ‘Whereas desire is the starting point of all pleasure, desire arises out of sense perception, for that which is devoid of sense perception is also free of passion.’

So desire, epithymia. What eros is, ideally, at the level of the nous, desire is at the level of the soul. In Evagrius’s system, the human being is tripartite: spirit or nous, soul, and body. The soul stands midway between the nous and the body. It mediates, as it were, between the nous and the body. And that means the soul is, as it were, caught between the nous’s innate noetic knowing and the fleshly body’s innate power of sense perception, of aesthetic knowing, sensory knowing. And in Evagrius’s system it is the fleshly power of sense perception that gives rise to the soul’s power of desire, which is the reflection on the level of the soul of the erotic power of the nous. And therefore pleasure is the expression on the level of the embodied soul of the blessedness, the spiritual delight that the nous experiences when it attains the object of its erotic desire, God.

So there’s a sort of mirroring going on. The psychological dynamic of sense perception provoking desire leading to pleasure is the inverse image of the noetic dynamic of spiritual perception giving rise to eros leading to spiritual delight. And so you see a mirror image. Spiritual delight, sensual pleasure. Spiritual perception, sense perception. Eros, desire. And the soul caught between the two.

And so, fleshly sense perception is the starting point of what Evagrius calls passion. And this means that praktikē, the first stage of the spiritual life, entails becoming, as Evagrius puts it, devoid of sense perception.

I want to make one thing perfectly clear, though, before we go on. That this does not mean that Evagrius taught that the body, or even the fleshly body, is evil. Not at all. The nous is incarnate as an animated body — which is to say the nous exists as a soul animating a body of flesh — because God has decreed that for the nous, to train the nous to direct its eros properly toward God by resisting the soul’s tendency to desire sensual pleasure. Our embodied life is a wrestling ring and we are ultimately minds undergoing training in spiritual athletics. Or this life is a battlefield and our minds are undergoing training in spiritual combat. And I should say, this training not only teaches our nous to desire God properly, but also strengthens the nous’s capacity to struggle to attain that object of erotic attraction.

So that’s the first thing to make clear. The fleshly body is not evil. The fleshly body has been made by God, given us by God, as a means of spiritual growth.

The other thing to point out is that when Evagrius says that to be free of passion is to be devoid of sense perception, he’s not really saying that our five senses cease to act. More that our minds are not attached to sense perception, as we’ve said many times on Life Sentences before. Although one might also wonder, given that according to Christian eschatology, the heavens and the earth as we experience them — the sense-perceptible heavens and earth — are passing away, and a new heaven and a new earth waiting to be revealed, we might wonder whether in the new heaven and on the new earth, having acquired the spiritual bodies of our resurrection, our perception of things will be so transformed as no longer even to resemble sense perception as we experience it now. So perhaps in the end, in the next world, when Christ is revealed in all his glory and the kingdom has truly come, sense perception may have been nullified.

So that’s chapter 4. A complicated chapter, one that requires careful study, because it really lays down the fundamental principle of the stage of praktikē, laying out the logic of all of our ascetical labors.

Now chapter 5:

Whereas against hermits the demons wrestle nakedly, they arm the more negligent of the brethren against those cultivating virtue in coenobia or small brotherhoods. The second war is much lighter than the first, since it is impossible to find on earth men bitterer than demons, nor indeed anyone at all who is able to endure all their malice all at once.

Thank God! A less complicated chapter than the previous one. It’s important for us though.

Evagrius is writing for monks. In fact, he’s writing mainly for hermits. Hermits, he says, are attacked directly by the demons. Whereas non-hermits, he says, and this includes us as ordinary people living in the world, he says we are attacked indirectly through other people, the more negligent of the brethren, he says.

If you think about it, this is linked to what Evagrius has said just before when he said that to be free of passion is to be free of sense perception. So, if you imagine a hermit, he’s withdrawn entirely from the world. Perhaps he lives in a cave. Perhaps he hardly leaves his cave. He has basically restricted his powers of sense perception as much as is humanly possible. The demons, therefore, cannot use sense perception to attack him. They have to attack his soul directly.

Whereas we live in the world, we are immersed in sense perception. Therefore, demonic temptation tends to attack us through the senses. We see something and instead of contemplating it dispassionately, we desire it passionately. In Evagrius’s mind, a demon is near. It has participated in the dynamic that leads us to desire the object passionately. Or we’re with someone. They do something to irritate us. We are angry. Outwardly or only inwardly, we express resentment, contempt, or hatred for that person. Again, in Evagrius’s mind, a demon is near and has seduced us into hating our fellow human being.

As Evagrius has said, the demons are very bitter. They are without remorse. Their malice against human beings knows no bounds. And therefore, hermits who are being attacked directly by demons, not indirectly via the senses, experience spiritual warfare, experience the malice of the demons, to a much greater degree.

And then Evagrius says that no one, whether a hermit or not a hermit, no one could endure all the malice of all the demons all at once. This is a sign that our spiritual war against the demons falls within the compass of God’s providence. The demons don’t know it, but they are in fact instruments of God’s providence. God grants them a certain degree of liberty to attack us, but he restrains them as well. If it were up to the demons, they would all at once totally destroy every human soul. God does not allow this. The demons are largely chained up. God’s providence grants them only a certain degree of freedom to attack us, not all at once, but one by one, and never more than we can endure.

This is related to what I was saying earlier about God having given us these fleshly bodies of sense perception. God has also granted the demons a certain scope to attack us because God knows that wrestling against demonic temptation is good for us. God, however, is overseeing the whole process. Therefore we can enter in upon spiritual warfare with confidence, faith in God, knowing that he will never allow us to be tempted beyond our strength, and that if we remain focused on God, trusting in his goodness, trusting in his salvific power, he will in the end, through us, triumph over his enemies.

So that’s chapter 5. The only other thing to point out about this chapter is that though, as I said, Evagrius is writing mainly to hermits, what he tells them is still very useful for us. By describing spiritual warfare at the level of the mind, which is the level at which hermits are engaged in that war, he helps us to engage in spiritual warfare at the level of the senses because the principles are the same. Whether the demons are attacking us through our senses, or attacking us in our minds through the impassioned memories that we have of sense perception, it’s basically the same. Whether through the body or through the memory, the logic of spiritual warfare is the same.

And anyway, though schematically we can say that hermits fight the spiritual war in their minds, and we fight the spiritual war in our bodies, that’s a simplification. In fact, the spiritual war is ultimately entirely of the mind. And though yes, we live more immersed in sense perception than hermits, even so we are still noetic beings and our life as Christians engaged in prayer and worship is still a life lived at the level of the nous and to that extent at least, what Evagrius writes to hermits applies to us.

Okay, so those were the first five chapters of The Praktikos. But before I wrap this up, I just want to return to the fourth chapter and, really off the top of my head, suggest some ways in which what Evagrius is saying in that chapter relates to the story of the fall of man as recounted in the Old Testament.

If you remember, Evagrius in that chapter writes this: ‘Whereas desire is the starting point of all pleasure, desire arises out of sense perception.’

Now, the word pleasure in Greek is idhoni (ἡδονή) It’s the root of our English word ‘hedonism’. In Hebrew, the word for pleasure is ayden (עֵדֶן). It’s remarkable on the face of it how similar those two words seem: ayden on the one hand, idhoni, on the other hand. Perhaps you can hear the similarities: ayden, idhoni.

Well, that Hebrew word ayden, which is the Hebrew word for pleasure, is the name of the garden that God plants in the second chapter of Genesis: the Garden of Eden, the Garden of ayden, of pleasure. This alerts one to the possibility, at least, that the very first hearers of the story of the Garden of Eden would have known right at the outset that the story has something to do with pleasure. And indeed, in chapter 3 of Genesis, pleasure makes its appearance.

After the serpent beguiles Eve and tells her not to listen to God, because if she eats of the forbidden fruit, as he says, ‘You will not surely die, for God knows that in the day you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.’ And the text continues, ‘So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, that it was pleasant to the eyes and a tree desirable to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate. She also gave to her husband with her, and he ate. Then the eyes of both of them were opened.’ So you see there that Eve, looking upon the forbidden fruit, was enticed by the prospect of pleasure. The fruit was good for food, it was pleasant to the eyes, it was desirable to make one wise.

Returning back to chapter 4 of the Praktikos, remember, Evagrius says that desire, which is the starting point of all pleasure, arises out of sense perception. The story of the Garden of Eden and the Fall of Man in the second and third chapters of Genesis is susceptible to infinite interpretation. It is a very deep story, extremely profound in its implications. A lifetime of contemplation would not reach the depths of this story. And yet one of the ways in which the Fathers of the Church interpret the story is remarkably similar to what Evagrius is communicating in this chapter.

According to this way of interpreting the story, Eve is sense perception. That’s what she symbolises in the story. Her husband, Adam, is the nous, is noetic perception. If you remember, earlier in the story, before Eve is created, the animals are paraded before Adam and he names them. He knows their names. This, according to this interpretation, is a symbol of the gnosis or knowledge which naturally resides in the nous. When dispassionate and clear, the mind knows the true natures of created things. The mind knows their names. This is what Evagrius called the kingdom of the heavens: dispassion of soul accompanied by true gnosis of beings.

And yet, God said, ‘It is not good for the man to remain alone.’ It is not good for the nous to remain alone, contemplating only the noetic dimension of reality as it pre-exists in the mind. God says this is not good, this is not the reason why human beings are created. No, the human mind was meant to unite, in a single act of knowing, the spiritual and the material, the noetic and the sensory, the thing in itself and the way in which that thing appears or is displayed. Unique among all created things, the human being’s mind unites all the dimensions of reality. Spiritual, material. Invisible, visible. All of it. And so as long as Adam remained alone in the garden, things were not yet good according to God.

So what happens? He puts Adam to sleep and from within Adam he draws out Eve, sense perception. Later on in the story, Adam will give his wife that name, Eve, and the text explains the meaning of the name, saying that the woman was ‘the mother of all things’. If Adam, in a way, is the father of things by knowing their names, the woman is the mother of all things by giving everything a body, a form, by being the means by which a thing displays itself to other things. The human being is only complete, is only good, when both of these poles of knowing exist in proper union, the noetic and the sensory.

And as Evagrius points out, sense perception gives rise to desire, and desire is the starting point of all pleasure. We see that play out mythologically in the story. The serpent, which according to Christian tradition is the devil — and we’ll have a lot more to say about him in further episodes — beguiles sense perception, tricking it into mistaking the appearance of things for the things themselves, and therefore into replacing the spiritual delight that comes from union with her husband, for the pleasure of the senses. And so she eats.

However, and this is so important, at this point in the story the fall of man has not yet happened. After all, what do we call it? The fall of man. So when does the fall of man happen? What does the story say? ‘She also gave to her husband with her, and he ate. Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they knew that they were naked, and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves coverings, and they heard the sound of the Lord God walking in the garden in the cool of the day, and they hid themselves from the presence of the Lord God among the trees of the garden, and the Lord God called to Adam and said to him, “Where are you?” So he said, “I heard your voice in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked, and I hid myself.” And he said, “Who told you that you were naked? Have you eaten from the tree of which I commanded you that you should not eat?”’

You see, it is Adam who was not supposed to eat. You might say, in terms of the story, Adam should have prevented Eve from eating — and as the text makes clear, he was there with her, it says, so why did he not prevent it? Nonetheless, the blame lies with Adam, and as we continue on through The Praktikos of Evagrius Ponticus, we will see that indeed sin lies in the nous, and therefore the therapy that Christianity provides — Christianity which is, as Evagrius said, the dogma of Christ our Saviour — is a therapy for the nous, returning it to right relationship both with its spouse, its powers of sense perception, and with its Lord, God Almighty, in whose image the nous has been created.

We might have occasion again to return to the story in the Garden of Eden. As I say, it is full of mysteries which one can contemplate to great profit.

But for now, the interpretation I’ve just suggested does at least indicate that Evagrius’s system of asceticism, contemplation, and ultimately union with God in prayer, is grounded in the Scriptures. He received this teaching from the Desert Fathers who preceded him and they received this teaching ultimately from the Apostles to whom the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Christ, revealed the hidden meanings of the Scriptures, lifting the veil from their eyes.

So this desert tradition is scriptural, it is traditional, it is philosophical, it is intelligent, it is ascetic, it is everything, it is our faith.

That’s it for this episode of Life Sentences. In the next episode, we will continue reading The Praktikos by Evagrius Ponticus. We will read through the next ten chapters in the text. These chapters are fascinating. They are where Evagrius first introduces his extremely influential scheme of eight primary demonic temptations, a scheme which in the Western Church would in time develop into the Seven Deadly Sins that we all know about. Well, they started with Evagrius as eight demonic temptations and next time he will introduce them to us.

Until then, I thank you for listening. I hope you enjoyed it. If you enjoyed it and if you haven’t taken out a paid subscription already, I do beseech you, consider taking out a paid subscription to Life Sentences. It does take a lot of work preparing these texts, I can tell you, especially a text by Evagrius Ponticus. It takes a lot of time pondering over the text, scrutinizing the original Greek, scrutinizing all the translations, re-translating pieces where I feel earlier translations didn’t quite get it right. It’s a lot of work. Not to mention recording the episodes, editing the episodes. I really appreciate the financial support.

If you would like to take out a paid subscription, please go to wisdomreadings.substack.com, where you can sign up. That’s wisdomreadings.substack.com. If you have taken out a paid subscription, I am deeply grateful. Thank you so much. Without you I could not maintain the Substack.

And with that said, until next time, stay well.

Share this post