What follows is a complete transcript of this week’s podcast episode, which you can listen to in the Substack app or via your preferred podcast platform.

The podcast is designed to be listened to, so I encourage you to listen. But I’m also providing transcripts, as you may want to read along as you listen.

Welcome to Life Sentences, an exploration into the wisdom of the ancient Church Fathers, presented by me, Thomas Small.

In this episode, Evagrius Ponticus guides us further into the inner workings of the rational soul, revealing the eight basic demonic temptations which subvert our minds and plunge us into irrational and spiritually lethal passion.

Last time, we began Evagrius’s seminal text, the Praktikos. As its name suggests, the Praktikos is Evagrius’s presentation of the fundamentals of praktikē, the first stage of the spiritual life, the stage we’re all in—and in my case only barely in. Praktikē focuses on combating the passions in pursuit of purity of heart, contemplation, and dispassionate love. In short, the Kingdom of Heaven.

In this episode we’re going to continue our journey through the Praktikos. However, first we’re going to say a bit more about Evagrius’ life.

When we last left him, it was the year AD 379. He was thirty-four years old. His spiritual father, St Basil, had recently died. And so, leaving Cappadocia, he had just arrived in Constantinople to assist St Gregory of Nazianzus in his fight against the Arians.

Now, we don’t have time to delve too deeply into the Church’s struggle against Arianism. The basic issue was this. The Arians taught that the Word of God—Christ the Logos—was a created being. The greatest, most illustrious, most powerful created being, but a created being nonetheless. And some Arians had taken this teaching about the createdness of the Logos to its logical conclusion: they also claimed that the Holy Spirit was a created being.

These are the heresies that St Gregory had been invited to Constantinople to combat. He was asked to defend the faith proclaimed at the Council of Nicaea fifty-four years earlier in AD 325. Namely that the Logos of God, the Son of God, is, just as the Father is, eternal and uncreated; that the Word of God is one in essence with God the Father; that the two are one God; and therefore, so Gregory would forcefully argue, that God’s Spirit is also one in essence with them both; that the Holy Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—are one God.

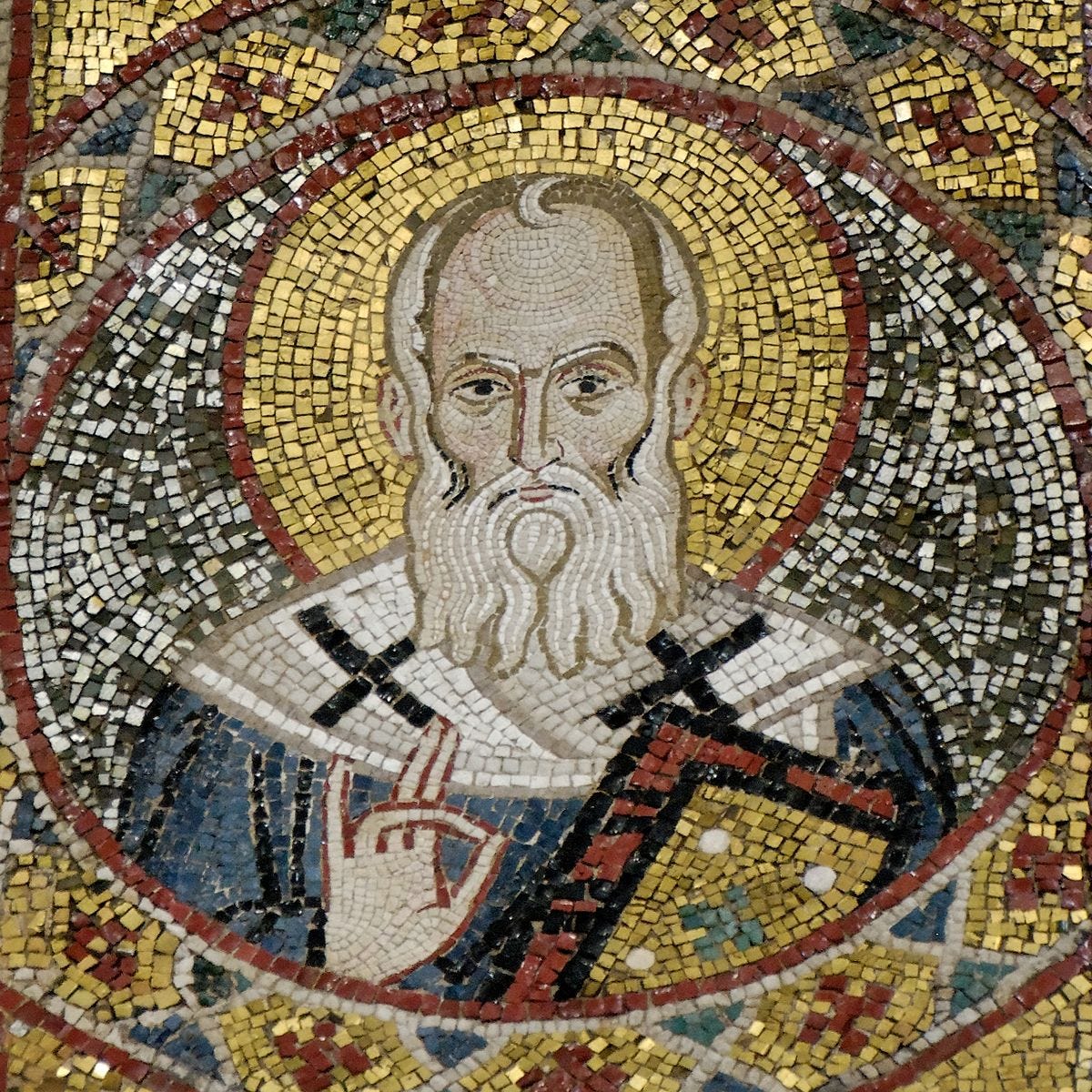

Now I have to say more about St Gregory.

St Gregory of Nazianzus is an immensely attractive personality in my view. As we learned in previous episodes, he was a great friend—the best friend, really—of St Basil the Great. They had met in Athens, where they were both studying philosophy. Later they lived together in the monastic retreat that St Basil had founded near Evagrius’s hometown in Pontus. Their connection was deep and abiding.

And yet they were very different. St Basil was the more forceful character, perhaps even more ambitious. We recall what Basil’s younger brother, Gregory of Nyssa, said of him, that he had grown pompous and superior during his studies in Athens. Basil of course struggled manfully against this tendency, but it remained part of his temperament.

Basil’s friend Gregory of Nazianzus, by contrast, was much more retiring, much more instinctively contemplative, perhaps even more sensitive, more imaginative. For example, Gregory would become renowned for his poetry, which is both beautiful and spiritually, theologically, and metaphysically profound. Following Gregory’s death, his reputation was such that he became known as ‘the Theologian’ in the memory of the church. St Gregory the Theologian, as he is called in the Christian East, became a towering figure in the intellectual and spiritual tradition of eastern Christianity. His prose and poetic works became foundational to Byzantine education in the Greek language, playing a role alongside the ancient Greek classics of Homer, Hesiod, and Plato.

Now, Gregory’s retiring nature wasn’t just a personality quirk. It played out in very concrete ways. For example, when St Basil appointed him as bishop of Sasima, a dusty little town in the middle of nowhere, Gregory basically ignored the assignment. Gregory felt that Basil had sent him there not because it was a spiritual calling, but as a kind of political manoeuvre in Basil’s struggle to organize the Nicene bishops of Cappadocia against the Arian faction, and Gregory wanted no part in that political game. So he just didn’t go.

A few years later, when his father, who was bishop of their hometown of Nazianzus, passed away, the people there naturally looked to him to step in as bishop, and Gregory again found himself in a leadership role he didn’t want. For a time, he did help manage things, but always with the understanding that he wasn’t committing to the job. Eventually, he stepped back and insisted they find someone else, someone with the strength to guide the community full time.

So, when Evagrius arrived in Constantinople in 379, the Gregory he joined wasn’t a lofty church bureaucrat sitting on a throne. He was a reluctant leader. An orator and poet whose deepest desire was to live in quiet contemplation, but who was drawn by a sense of duty into the heart of the most contentious theological battle of his time. He was more like a missionary theologian, preaching the Nicene faith to a city where the churches had been taken over by Arians.

The orthodox Nicene Christians there were in the minority, reduced to gathering in a small chapel called the Anastasia—literally ‘the Resurrection’. It was in that humble space that Gregory delivered some of the most powerful theological orations in Christian history, defending the full divinity of the Son and the Holy Spirit with such clarity and grace that people began flocking to him.

This was the Gregory who took Evagrius under his wing, a man with a profound intellect, a poetic soul, and an almost tragic sense of duty. A man who kept trying to walk away from his calling, but whose voice was so powerful that the church kept calling him back.

And after this short break, we’re going to stand alongside Evagrius and the rest of the huddled faithful as they listen to St Gregory and learn from his extraordinary theological illumination.

So here we are. It’s the year 379. Evagrius is standing beside us. We’re inside the Resurrection chapel in Constantinople. It was still a newish city. Constantine the Great had founded it less than fifty years before, expanding the very ancient city of Byzantium beyond all imagination.

Constantinople. The new Rome built by Constantine for the glory of God—and yet since that time all the way up to the year that Evagrius arrived, the city had been dominated by Arians. The council of the church that the Emperor Constantine had called, and which convened across the Bosphorus in the city of Nicaea, had failed to unite the Church. Constantine’s successors, especially his son Constantius II, had all but repudiated the council and had thrown in their lot with the Arians.

So yes, despite the grandeur of the new city, despite the majesty of the churches, of the government buildings, of the circus, of the Colosseum, despite all of that, in Evagrius’s mind, in St Gregory’s mind, the true faith was just a tiny flickering light in the darkness of heresy. For that reason, though I promise we will shortly return to the Praktikos, I think it’s instructive to stand with Evagrius and listen to his master, St Gregory.

Specifically, St Gregory’s Oration 32. Scholars think it was likely preached in the year 379, and so it is likely that Evagrius was present when St Gregory stood in the chapel of the Resurrection and first delivered it. It’s fair to assume that St Gregory’s words struck Evagrius powerfully and would go on to influence his own mind, his own soul, his own heart, as he grew in the faith and became in time a celebrated teacher himself.

So this is the first of two excerpts now, which I will read from St Gregory the Theologian’s Oration 32.

St Gregory writes:

God is light, the most exalted light, of which a certain brief emanation and radiance reaches downward, a pure light even if it seems beyond brightness. But do you see? He tramples on our dark gloom, and yet he appointed darkness as his veil, placing it between himself and us, just as Moses long ago placed the veil both over himself and over the hardness of Israel, so that darkened nature might not easily see the ineffable beauty—which is worthy of only a few and not easily attainable—and cast it aside carelessly, because it was acquired so easily.

But light may commune with light, always being drawn upward toward the height by desire. And the mind, having been cleansed, may draw near to the most pure. And the light appears now in part, later in full. Now as a reward for virtue, or for inclining from here toward the most pure; later as full likeness to the most pure.

For now, he says, we see through a mirror, in an enigma, but then face to face. Now I know in part, but then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known. How great is our lowliness! And yet how great the promise, to know God as much as we have been known! These are the words of Paul, the great herald of truth, the teacher of the nations in faith, the one who completed the vast circuit of the gospel, who lived for nothing but Christ, who ascended to the third heaven, who was a seer of paradise, who longed for dissolution because of his desire for perfection.

Wow! Just imagine! Imagine sitting there, standing there, in that chapel in Constantinople, hearing St Gregory deliver a sermon like that. And you know, you can see why I think maybe Evagrius would have been very influenced by a sermon like it. A lot of themes there are resonant with things that Evagrius writes a lot about, things that we’ve already seen in Evagrius to some extent. We’ll see more.

There’s so much in that passage by St Gregory that we could focus on. Just a few things. At the beginning he says God is light. And then he clarifies that. He says: the most exalted light. I think that implies, and what he goes on to say indicates this as well, that there are less exalted lights. Perhaps, for example, the natural light of the human mind. That is also a light. Made in the image of God, the human mind, like God, is light. But not the most exalted light.

And yet St Gregory says that a certain brief emanation and radiance of this most exalted light reaches downward. By which he means it reaches downward into our minds where the exalted light communes with our light and draws it upward, he says, toward the height by desire. This is very similar, if you remember, to what Evagrius was saying in the last episode about the eros of the mind giving rise to a natural noetic desire for union with God.

So yes, God is the most exalted light. And when it reaches down, St Gregory says, it is a pure light, though he says it seems beyond brightness. The most exalted light of God, when it communes with the natural light of our mind, seems dark. Beyond brightness. Compared to the light of our mind, compared to knowledge as we usually experience it, God’s light and the knowledge of God is dark, not light. But it is light, exalted light, not dark, but beyond brightness.

And then, quoting the Psalms, St Gregory points out what seems a contradiction. He says God both tramples on our dark gloom—his light, entering our mind, scatters the darkness of our ignorance—and yet God, according to the Psalms, appoints darkness as his veil. He surrounds himself with a kind of darkness. And St Gregory says that God places this veil between himself and us so that our nature, when it is darkened, he says, when it is fallen, absorbed in sense perception, entwined with fleshly desire, inclining towards egoic passion, unstable, unrooted in faith that has been tested and refined; so when our nature is darkened like this, God veils himself in darkness, St Gregory says, so that being weak, we’re not put in the position of casting the ineffable beauty of God’s pure light aside carelessly. St Gregory says that God fears that if we acquire his light easily, we will cast it aside carelessly. And this is the essence of sin. God is protecting us from this by revealing himself to us as darkness, as something that requires faith, faith in the presence of the God who veils himself in darkness, faith which in itself strengthens us so that when God reveals his ineffable beauty to us in all its glory, we will not cast it aside carelessly. We will cling to it.

And so, yes, this light, which is beyond brightness, which veils itself in darkness, communes with our light, the light of our minds, draws us upward toward the height by desire, and by drawing the mind upward in that way, it cleanses the mind, St Gregory says, allowing it to draw ever nearer to the Most Pure.

And though now, he says, the light appears only in part, only given in glimpses; later it will appear in full, and will appear, he says, as our being made fully like God. The light of our minds, having been made pure, will unite, will commune with the most exalted light of God, and will become like God in that communion.

And when St Gregory then goes on to quote that famous passage by St Paul—‘For now we see through a mirror in an enigma, but then face to face. Now I know in part, but then I shall know fully, even as I have been fully known’—St Gregory uses this to express the incredible mercy and love of God. We are so low, he says, and yet God is going to transform us into the beings that he knows we are, in his mind, that he has intended us to be. That is what the revelation of his light in our minds does. It conforms us, slowly but surely, to the image God has of us in his mind from eternity.

It’s an incredible vision, an incredible sermon. And there at the very end of this excerpt, having praised St Paul, having emphasized just how exalted St Paul’s spiritual attainment was, St Gregory says that Paul longed for dissolution because of his desire for perfection. This is also referring to a passage in one of St Paul’s epistles where St Paul does say boldly, brazenly, that he would rather be dissolved, it says in Greek, so strong is his desire to depart and be with Christ. And when St Paul writes this, the context is a contrast that he is drawing between life in the flesh and life in the spirit. A life in the spirit which he makes clear is lived most fully after death. Here in the words of St Gregory commenting on St Paul, perfection is only finally achieved after we are dissolved, after this fleshly body in the mode we currently inhabit it dissolves.

The process called death that we tend to fear is in fact a process guided by God in the Holy Spirit towards union with Christ. It’s a mystery and St Gregory would certainly say for this reason, death must not be feared. Death is in a way that veil which God sets between his light and us, and in that context perhaps we see a meaning in the rending of the veil at the moment of Christ’s death on the cross.

Anyway, that’s the first of the two excerpts from this Oration 32 by St Gregory the Theologian. The next one—which is in fact a bit longer, though it requires much less comment, it’s quite straightforward—this next one I wanted to read because I think it has a lot to tell us about Evagrius, and it also might gesture towards the way in which later on, Evagrius would fall into error and centuries later find himself anathematized by the church.

The context for this passage is St Gregory, who’s in Constantinople, remember, combating Arianism. He’s really annoyed at the amount of theological argument and disputation going on in general. He thinks that too many people who aren’t qualified to comment on theology are doing so. Are sticking their oar into a very fraught, complicated theological dispute, arguing with each other in public about theological questions—very exalted, very arcane theological questions. St Gregory thinks this is ruining the peace of the Church and wishes that these people would be silent. He thinks they should focus on other things, not theology.

He writes:

Why fly off to heaven when you are earthbound? Why build a tower when you lack what you need to complete it? Why measure the waters with your hand, or the heavens with the span of your fingers, or the earth in the cup of your palm—great cosmic elements measurable by the Creator alone?

First know yourself. Consider what is within your grasp.

Who are you? How were you formed? How were you brought into being, so that you might be the image of God, and yet you have been bound to something inferior?

What sets you in motion? What is the wisdom surrounding you? What is the mystery of your nature?

How is it that you are measured by place, and yet your mind is not so confined, but rather, while remaining in the same place, it comprehends all things?

How small the power of sight is, and yet how vast its reach! And does it simply receive what is seen, or does it reach out to grasp it?

How is it that the same thing both moves and is moved, being governed by deliberate choice?

What is the division of the senses? And how does the mind through them communicate with external things and take into itself what is from outside?

How does it apprehend forms?

How is speech the offspring of the mind, and how does it generate speech in another mind? How is meaning communicated through speech?

How is the body nourished through the soul, and how does the soul, through the body, share in suffering? How does fear stiffen and courage loosen? How does sorrow contract and pleasure spread out? How does envy melt, pride lift up, and hope lighten? How does anger drive one mad and how does shame cause one to blush through the blood, the one by its rushing forth, the other by its withdrawal? How are the marks of the emotions imprinted on the body?

What is the leadership of reason, and how does it govern all these things, and tame the movements of the passions?

How is the incorporeal held together by blood and breath? And how is the cessation of these things the departure of the soul?

Understand these things, O man!

I love that passage. If you think, it was first written in 379 AD. So how long ago is that? You know, 1650 years ago? That’s a long time. And yet these are all questions that the intelligent man still asks himself. Questions that we don’t really have answers to, even if we think we do.

For example, when he asks, how is it that the same thing both moves and is moved, being governed by deliberate choice? He’s talking about our subjective self, our soul, and ponder it. Think about it. Your soul, your self, is self-moving and yet is also moved from outside at the same time. External stimuli, or even impulses, memories, they move the soul, they impact the soul, and yet the soul itself moves through a power of deliberate choice. Both of these things are true. It is a total mystery. A total mystery that there, between movement and being moved, lies the free will, the rational will, deliberating, choosing, intending.

It’s a mystery. It was a mystery in 379. It’s still a mystery. And St Gregory encourages us to contemplate mysteries like these. Even though he wrote extremely eloquently, articulately, illuminatingly about theological things, and certainly expected his congregants to be faithful to the dogmas that he was explaining to them, nonetheless he doesn’t want them to think about them too much. He wants them to contemplate themselves.

And as we’ve already seen so many times on Life Sentences—and certainly in our reading so far of Evagrius—contemplating ourselves properly, getting to know ourselves as rational spirits properly, is the foundation of the spiritual life. As Evagrius’s first spiritual father, St Basil, told us: be attentive to yourself. St Gregory is here saying the same thing. And certainly, standing there, listening to this sermon, Evagrius must have taken it in. Because when, later, he would leave Constantinople and travel to Egypt, he would become the greatest theoretician of the subjective self’s experience of spiritual life in Christian history.

That story, however, how he went from Constantinople to Egypt, we will save for another episode as we continue exploring Evagrius’s remarkable life story. For now, we are going to leave him once again in Constantinople with St Gregory and turn back to the Praktikos.

If you remember, the Praktikos is divided into small chapters, and in the last episode we went through the first five chapters, which were really introductory. The rest of this episode will cover chapters six through fourteen, and this section of the Praktikos is known as On the Eight Logismoi.

Yes, that’s right: On the Eight Logismoi. That is the plural of a Greek word, logismos. And certainly before we launch into this section of the Praktikos, we need to talk about logismoi, logismos.

So, it’s a Greek word, as I say. A technical term of immense importance to the tradition that we’re exploring in Life Sentences. Logismos, the singular; the plural, logismoi, ‘logeesmoy’, if you like, though it’s pronounced ‘logeesmee’ in modern Greek. And if you absolutely need to you can think of logismos as logism—but that’s a terrible word. We’re going to use the Greek word logismos.

So, these days this word is more often than not translated as ‘thought’ or ‘thoughts’. You’ll find this part of the Praktikos is almost always translated On the Eight Thoughts. Now I’ve translated it, On the Eight Logismoi, because I want to draw attention to the technical meaning of logismos. And really, I want to encourage you not to think of it simply as a thought. I think that’s a bad translation for logismos. I think that it’s a mistranslation, really, and gets in the way of understanding the term. Which, as I say, is so key to understanding this tradition.

So, logismos is derived from the Greek verb logizomai, meaning ‘to reckon’, ‘to calculate’, ‘to reason’, or ‘to consider’. And logismos is the verbal noun. So, logismos, more than just ‘thought’, means something much more specific, like ‘reasoned calculation’, ‘mental reckoning’, or ‘deliberate thought’. In Evagrius, logismoi are mental calculations, mental deliberations that arise in the soul and can either aid or hinder the spiritual life. Logismoi can come from angels, they can come from yourself, or they can come from demons. And Evagrius focuses almost entirely on the demonic kind to help you resist demonic logismoi. However, these are not mere thoughts in the passive fleeting sense. But rather, structured and deliberate movements of the mind, much closer to calculations or mental scenarios. A calculated chain of reasoning. A purposeful chain of thought. A mental stratagem, you might say. A chain of thought with a strategic dimension.

So, in another text, Evagrius uses the example of the devil’s temptation of Christ in the wilderness to illustrate a demonic logismos. If you remember, the devil attacks Christ with the logismos of gluttony. Christ has been in the desert for forty days fasting and then, the text says, he grows hungry. The devil attacks him with this logismos: ‘If you are the Son of God,’ he says, ‘command that these stones become bread.’ Evagrius points out that the logismos itself—the stratagem the devil employs, the bit of calculated reasoning here—isn’t in itself openly gluttonous. It’s not targeting Christ’s hunger. It’s not trying to make Christ feel hungrier. It’s targeting what the devil assumes is Christ’s vanity. ‘If you are the Son of God, command that these stones become bread.’ Not knowing that Christ is actually divine, and therefore free of any taint of sin, including vanity, the devil thinks he can get Christ to break his fast, and therefore succumb to gluttony by attacking his vanity. The devil fails, but nonetheless it is an illustration of what a logismos is: a calculated stratagem which arises in the soul, in the mind, trying to talk you into doing something or giving your assent to something, often by tricking you.

So you can see why the standard translation ‘thought’ does not do justice to the concept logismos. It’s a much more complicated, nuanced, sophisticated concept. A chain of thoughts, a chain of reasonings arises in your mind, pursuing a strategy with a deliberate end in mind, getting you to sin. That’s a logismos, a demonic logismos. And this section of the Praktikos on the eight logismoi is where Evagrius sets out his stool. Where Evagrius will first initiate us into the science of discerning demonic logismoi.

So here it is. Evagrius Ponticus, the Praktikos, chapter 6:

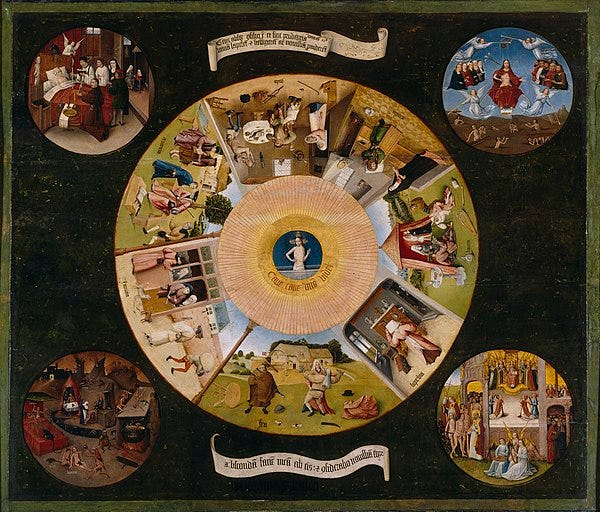

There are eight overarching logismoi. Every other logismos falls within one of the eight. First, the logismos of gluttony. And, after it, the logismos of fornication. Third, that of avarice. Fourth, that of sorrow. Fifth, that of wrath. Sixth, that of acedia. Seventh, that of vainglory. Eighth, that of pride. Whether all these logismoi trouble the soul or not is not within our power. But whether they persist or not, or set passions in motion or not, that is within our power.

So there you have it. The eight basic logismoi. The eight basic demonic temptations according to Evagrius Ponticus. As I mentioned at the end of the last episode, this scheme of eight basic logismoi would in time become the famous Seven Deadly Sins of the Western Christian tradition. So the Evagrian tradition, when it reached the West, underwent some development, some transformation.

And in fact, it reached the West via St John Cassian, Evagrius’ disciple. And notice what Evagrius says there at the very end. He says exactly what John Cassian said Abba Moses said. That it is not within our power to prevent logismoi from troubling our souls. It is not within our power to prevent demonic thoughts. Absolutely not. But it is within our power whether or not they persist. It is within our power to resist them. It is within our power to prevent them from setting our passions in motion. Abba Moses said precisely that. John Cassian learned it from Evagrius.

So yes, eight basic logismoi. Eight basic demonic temptations. First, gluttony. Second, fornication. Third, avarice or greed. Fourth, sorrow. Fifth, wrath. Sixth, acedia or sloth. Seventh, vainglory. Eighth, pride.

Evagrius wants us to know these eight. He wants us to learn how to discern them when they approach. He wants to unmask them so we can see the demonic stratagem for what it is, the logismos for what it is: a chain of thought trying to set in motion one or other of these passions in us, which is what we want to prevent and which is within our power to prevent.

So that’s chapter 6. Before we move on to the next chapter, I have to talk about passion, pathos. Now this concept, pathos, passion, is rooted in ancient Greek philosophy and was particularly emphasized and developed by the Stoics. Stoicism, especially Stoic ethics, had a huge influence on Christianity. In fact, from the beginning. There’s a lot of evidence that St Paul had been influenced by Stoicism, and he employs some Stoic terms in the Epistles. This is in fact unsurprising, given that in the ancient world, the city of Tarsus, where St Paul grew up, was a world centre of Stoicism.

So, the ancient Greek philosophers, and specifically the Stoics in this case, were very adept psychologists. They paid close attention to themselves, and they learned certain phenomenologically verifiable things about themselves, about the workings of their souls. The first Christian to incorporate the Stoic theory of the passions into his writings was Clement of Alexandria, a late-second-, early-third-century Christian philosopher. And through Clement, the Alexandrian tradition, and therefore the Egyptian tradition, developed the science of the passions in great detail.

So, passion, pathos. The word comes from a Greek verb, paschō: ‘I feel, I suffer, I experience’. Paschō is the opposite of ‘to do’ or ‘to act’. It is ‘to be acted upon, to be affected’. Therefore, pathos is that which happens to one. An incident, an accident, an experience. Negatively, a misfortune or a calamity. These are things that happen to you. And psychologically, therefore, it can mean emotion or even sensation. Something that affects you from outside. Something towards which you are passive.

So why does this word pathos play such a big role in Evagrian psychology? To understand that, you have to understand the Evagrian framework of the tripartite soul.

So, in Evagrius, the soul is divided into three parts, the logistikon, the thymikon, and the epithymētikon. Apologies for all the Greek words, but I think it’s important that you know them.

So, the first and highest part of the soul is the logistikon, the rational or intellectual part of the soul. Logistikon, you can hear again the word logos there. The logistikon is associated with reason and intellect.

Then the next part of the soul is the thymikon or irascible part of the soul. This part of the soul is associated with anger and aggression.

And finally, the lowest part of the soul is the epithymētikon, the desiring part of the soul, associated with appetites and desires.

This scheme of the tripartite soul would become absolutely standard in Christian ascetical wisdom. And if you quiet your mind and pay attention to yourself, you will see why. It is simply true. At root, you, as a subjective self, as a soul, are a strange intercommunion or intertwining of rational, aggressive, and desiring powers. And one of the foundational parts of praktikē, of the first stage of the spiritual life, is to learn to keep these three powers, these three parts of the soul, in right relationship, in proper balance.

A few centuries after Evagrius, a great Father of the Church, St Maximus the Confessor, would write this:

A soul’s motivation is rightly ordered when its desiring power is subordinated to self-control, when its incensive power rejects hatred and cleaves to love, and when its power of intelligence, through prayer, advances towards God.

So, St Maximus is invoking the tripartite soul and he says that the lowest part of the soul, the desiring power, must be subordinate to the middle power or part of the soul, the irascible part, the thymikon, and both of them must be subject to the logistikon, the rational part of the soul. When the rational part of the soul, the highest part of the soul, the logistikon, when it is in charge, as it should be, the soul is free of passion. The soul has achieved what in Evagrian terms is known as apatheia. Apatheia, remember, being not apathy but impassibility, non-passive, being free from passion. Apatheia.

That’s when the soul is working properly. However, when the desiring and irascible parts of the soul subvert the natural order of the soul and subject the rational part to themselves, then the rational part, being subjected, being subordinated unnaturally, opens itself up to passion, to being passive, to being influenced from outside. The rational part is meant to be active, to be in control, to be subjecting the other parts to itself. It is not meant to be passive, to be subjected to them. And the passions are all the various modes in which the irascible and desiring parts of the soul subvert, attack, overwhelm, and enslave the rational part.

That’s the theory. And it’s absolutely vital that you understand this scheme if you’re going to understand Evagrius and, in fact, the whole Christian ascetical tradition. And though I say that this tradition is rooted to some extent in Stoicism, it is also biblical. For example, this passage from St Paul’s Second Epistle to Timothy. He writes:

But know this, that in the last days perilous times will come. For men will be lovers of themselves, lovers of money, boasters, proud, blasphemers, disobedient to parents, unthankful, unholy, unloving, unforgiving, slanderers, without self-control, brutal, despisers of good, traitors, headstrong, haughty, lovers of pleasure rather than lovers of God, having a form of godliness but denying its power, led away by various passions, always learning yet never able to come to the knowledge of the truth, men whose nous has been corrupted, worthless regarding the faith.

Or this from his Epistle to Titus:

For we ourselves were once also foolish, disobedient, deceived, serving various passions and pleasures, living in malice and envy, hateful and hating one another.

In both of those passages from St Paul, you can see terminology that we’ve met on Life Sentences many times before, and its whole perspective is totally in accordance with the Desert Fathers. In both passages he talks about passions. The word he uses is not exactly the same as pathos, but it is a word related to that lower part of the soul, epithymētikon, and he means the same thing: passions, desires that overwhelm the mind, that subject the mind to themselves.

He explicitly contrasts the love of pleasure with the love of God. This is that very difficult, very provocative, certainly very anti-modern Christian understanding, that fleshly pleasure is the opposite of God. To love pleasure is to hate God, and to love God is to hate pleasure. Which is to say, to hate sensual indulgence, to hate allowing your mind to be dictated to by pleasure.

And there he calls such men, men whose nous—he uses the word—has been corrupted. The corruption of the nous is the fall of man, as we discussed in the last episode. And Evagrius and all the Desert Fathers are helping us rehabilitate the nous.

And in that context, when St Paul says that we were once also foolish, the word translated ‘foolish’ there is anoētoi, which is to say ‘without nous, non-nous’, in which state he says once again, one serves passions and pleasures instead of loving God.

So that’s the basic idea of passions.

And now, having been introduced first to the concept of logismos, the demonic mental stratagem that is trying to trick you into sinning so that passions are set in motion inside you; having set all that out, when we get back from this second break, Evagrius is going to go one by one through the eight deadly deadly demonic temptations, beginning with the logismos that I am extremely well acquainted with: gluttony.

Right, we’re back. And Evagrius is going to tell us all about gluttony.

Here he goes. Chapter 7:

To the monk, the logismos of gluttony suggests the swift demise of all his ascetical efforts, portraying the stomach, liver, spleen, and dropsy, and a long illness, and the scarcity of necessities, and the lack of doctors. It also often brings him to the remembrance of certain brothers who have fallen prey to these sufferings. Sometimes this logismos persuades those very persons who have suffered such things to visit those who are practicing self-restraint and to tell them all about their misfortunes, as if those things had happened on account of their asceticism.

Okay, that’s chapter 7. That’s the logismos of gluttony.

A few things to point out.

First of all, the logismos is not in itself the passion. The logismos is not the passion of gluttony in your soul. Certainly it’s not the feeling of hunger or the feeling of desire for food. The logismos is a chain of reasonings. The logismos is the stratagem.

And notice, what is the strategy here? The logismos of gluttony here is not bringing fantasies of delicious food to the mind. It’s not attacking the monk with images of tankards of beer and delicious steaks. No, the logismos of gluttony is attacking the monk with images of illness, of weakness. It’s reminding the monk that there’s no doctor nearby, so what if he gets sick? Or making the monk anxious that he won’t have enough food. His health will decline. He’ll get sick, perhaps even die.

You see the strategy here. The demon is clever. He knows the monk is on the lookout for fantasies of food. So, in order to make the monk succumb to gluttony, he’s trying to make the monk anxious about his health. So the monk will say to himself, ‘I should really relax this fasting regime. It’s not good for my health.’ So immediately you see, the logismos is a strategy. A clever strategy, using anxiety over health to trap the monk in gluttony.

That’s one thing to point out.

Another thing to point out is that Evagrius has emphasized the two poles of demonic temptation. He first says, in effect, that the demon who is in charge of gluttony attacks your memory. So some monks are being attacked directly in their memories. Memories of people who have suffered illness, sickness, weakness and death come to the monk’s mind, convincing him that he too will suffer those things unless he relaxes his fasting regime. So a logismos attacks you directly. Or, he says, sometimes the demon of gluttony will attack someone else, persuading them to come and visit you so that they will tell you all about their health anxieties. This reminds us of what Evagrius told us last time, that advanced monks are attacked directly by the demons, but less advanced (and we are in that category) are mainly attacked by demons through other people—especially, Evagrius said, through the more negligent of the brethren.

Here’s an example of that. You’re sitting, minding your own business, trying to live your spiritual life, and someone comes to you and tells you all about how they’ve relaxed their fasting regime because they’re really worried about their health, and they realize that they’re losing muscle mass, and it’s really getting in the way of their workout regimen. And don’t you really think you should go for long walks? And, you know, you should have a balanced diet. Make sure you’re healthy! After all, I mean, health is ultimately more important than fasting... So someone else—not yourself, not the demon himself, but someone else—will come to you and try to influence you in this way.

Evagrius says this is the main way that beginners, that novices in the spiritual life—novices like us—are attacked by the demons. So it’s this other person, this negligent person, in Evagrius’s words, who is receiving the logismos, which is persuading them to come and bother you, to influence you, so that you will abandon your efforts at self-restraint, he says.

So that’s gluttony. The main takeaway is that the logismos of gluttony primarily inspires health anxiety in you. That’s that demon’s main strategy.

And it’s worth pointing out that if Evagrius is clear, he does not believe that fasting results in ill health. Now he might be wrong about that. But it’s certainly his view and it’s more or less the view of the desert tradition. Now, if you fast beyond your strength then you will certainly fall into ill health. And this is extremely possible and an extremely dangerous temptation—as a punishment really for the vainglory that is influencing you to fast beyond your strength. So, it’s very important if you are following the Church’s fasting rules to follow those rules and nothing more. We are all beginners. We do not want to fast more than we can. We are in fact instructed not to fast beyond the Church’s fasting rules. And if we do follow the Church’s fasting rules obediently and in good faith, Evagrius insists that that rational, reasonable, moderate degree of fasting will not negatively impact our health, and so that we must never listen to the demonic voice in our heads that suggests that it will negatively impact our health. That is the logismos of gluttony.

Okay, next, everyone’s favourite: Fornication.

Chapter 8:

The demon of fornication forces one to desire various bodies, and it attacks with greater fierceness those who are practicing self-control, to get them to give it up as leading to nothing. Polluting the soul, it weakens its works regarding those matters, and it makes the soul say and also to hear certain words as though the object were visible and present.

Okay, that’s fornication.

Evagrius is a little bit more circumspect here than he was about gluttony. I think for obvious reasons. It’s almost always the case in Christian ascetical writings that fornication is sort of tiptoed around. The Desert Fathers feared that if they went into specifics about fornication, their writings themselves would provoke or incite lust in their readers, which they would not wish to do. That’s not always the case. There are some very funny stories, particularly in the lives of the Desert Fathers, in which poor monks get up to all sorts of naughty things. But here Evagrius is being careful

Careful but specific. Notice he says the demon of fornication forces one to desire various bodies. The language there is remarkable. In Evagrius’s writings and in John Cassian as well, the demon of fornication is a particularly strong demon. It’s almost like he’s been granted special powers to force us to feel things. The demon of gluttony does not have the power to force us to feel hungry, but the demon of fornication does have the power to force us to feel sexual desire. Why is this? Or let’s say, why does Evagrius think this?

This is where I am going to have to be a little bit specific. If you’re sitting in a cave, being attentive to yourself with no distractions, and if you realize that you are this strange combination of rational soul and fleshly body, you will realize that your rational soul is not entirely in control of your body. Your body, as it were, has a will of its own. The sexual part of your body feels very much like it has a will of its own that, try as you might, your rational mind cannot wholly control. Certainly young men know exactly what this feels like. I can’t speak for women, but I can speak for young men. You know, you’re just living your life and suddenly, boom! You feel sexual desire and your body is directly implicated in that and you can’t do anything about it.

So I think in Evagrius’s mind, at least, this manifests this power that the demon of fornication has to force us to desire. The demon of gluttony is only attacking our minds, either directly or through other people, but the demon of fornication is making us feel sexual desire. That’s what we’re wrestling with.

And it says that it forces us to desire various bodies. Does that mean several bodies or various kinds of body? Is Evagrius there gesturing towards the spectrum of sexual desires that human beings feel? From heterosexual, homosexual, all the way down: bestiality, paedophilia, etc. Is Evagrius gesturing towards this spectrum and therefore saying that the demon of fornication has the power to force certain souls to struggle against sexual desire across that spectrum? I think probably that is the case.

And he says this demon attacks with greater fierceness those who are practicing self-control in this regard. And I think we all know that that is so. We’ve all experienced the truth of that. It can sometimes feel that you’re never more lustful than when you really set your mind to restrain your instincts in that regard. It’s one of the more irritating parts of life.

And notice here that Evagrius reveals why the demon of fornication is doing this. He does it not essentially so that we will fall into lustful activities of various kind. He does it in order to convince us to give up even trying to practice sexual continence or self-control. That’s his goal. Obviously in the short term the goal is for you to fall into sexual sin, but the main thing the demon is trying to do by attacking you so ferociously with sexual desire is to get you to stop trying to be chaste. To weaken your spirit. Evagrius says he’s attacking you, polluting your mind, he says, polluting your soul, so that your struggle against lust will be weakened. That’s what the demon is trying to do: to get you to give up.

And so, at the very least, I think we must keep this in mind. When we do fall, we must remind ourselves that the temptation is ultimately trying to get us to give up. Whereas when we fall, if we stand up, dust ourselves off, and repent, the demon has actually failed in his goal. So that should give us some courage. God knows, there’s nothing more dispiriting than those sorts of sexual fall. The shame, the disappointment, the sense of filth you feel. The temptation is really strong to just give up. To be so ashamed, to be so spiritually exhausted that instead of repenting and getting back on the wagon, you just shrug your shoulders and give up. That’s the real goal of the logismos of fornication, and that’s what we must be on our guard against more than anything else, the giving up.

Okay, on to avarice.

Chapter 9:

Averice suggests a lengthy old age, the weakening of the hands for manual labour, future famines and impending illnesses, the bitter things of poverty, and that it is shameful to receive from others what is necessary for one’s needs.

So, this logismos, the logismos of avarice, is not so different from the logismos of gluttony. Like the logismos of gluttony, the logismos of avarice is trying to make you feel anxious.

Specifically, anxious about the future. The logismos of avarice will tell you, you’re going to live until you’re a hundred years old. What will you do? How will you live for all those decades unless you earn a lot of money now? Unless you save a lot of money? Unless you build up your capital base? Invest in a pension. And in fact, you probably should get that bigger house. Why don’t you flip your house upwards? Get on the property ladder! Open another ISA. What about your stocks and shares? You better invest more. Could you possibly go for that promotion? It would pay you more. Because just think, what are you going to do after you retire? And what if you get sick! it says. You don’t want to rely on the state health system. Or charity! That would be shameful. Also, that would be a burden on others. You don’t want to be a burden on others, do you? That’s shameful. You should work now. Earn a bit more money. Save it. Keep it for yourself. Keep it for the future.

These are the sorts of logismoi that the demon of avarice attacks you with. Because at base, avarice is not about greed. Avarice is about stinginess. Avarice is about meanness. It’s about hoarding money for yourself instead of giving it away. That’s what avarice is. So, the demon here is trying to get you to save your money, not to give it away, by making you anxious about the future.

This is obviously in direct contradiction to our Lord’s commandment not to worry about tomorrow. Tomorrow will take care of itself, the Lord says. This is extremely hard. Giving your money away is the hardest thing in the world to do. It’s so hard that the Lord says that when he returns again in glory at the Last Judgment, he’s not going to ask you about your fasting. He’s not going to ask you about your fornication. He’s going to ask you about your generosity, your charitable giving. Did you help the poor? Did you feed the hungry? Did you clothe the naked? This is what he’s going to ask you.

Christ, the Gospel makes clear, is above all focused on avarice as the root of sin and passion in the soul. As the Scriptures say, the love of money is the root of all evil. Not especially the love of acquiring money, although that’s part of it, but mainly the love of hoarding money. Of keeping it to yourself instead of giving it away.

So that’s avarice. Next, sorrow.

Chapter 10:

Sorrow sometimes arises from the deprivation of desires, and sometimes it follows upon wrath. It arises from the deprivation of desires in this way. Certain logismoi, coming first, lead the soul into the memory of home, parents, and former ways of life. When they see the soul not resisting but instead following along and becoming scattered in the pleasures of the discursive intellect, then they seize it and plunge it into sorrow with the realization that these things are no more and, because of the present way of life, will never be again. And the wretched soul, having been scattered over the former logismoi is now contracted to the same extent, humbled by the latter logismoi.

Okay, so that’s sorrow. Or really, the first half of sorrow. Because Evagrius says that there are two primary causes of sorrow: when your desire is thwarted and when you’re very angry. He’s going to talk about that second kind next.

Here he focuses on the first kind, the kind of sorrow that arises from the deprivation of desires. And it’s actually very clear. It’s extremely relatable. He’s basically saying that the demon of sorrow attacks you with logismoi, with chains of thoughts in your mind, in your imagination, making you fantasize about things that you love, that you want, that you miss.

Now, because he’s writing to monks, he says that the demon will make them think of their home, their parents, and in general the life they led before they became monks. Perhaps we won’t be attacked with quite the same fantasies, or perhaps we will. Nostalgia can be, I think, a very powerful demonic fantasy. A lot of people spend more time than they should daydreaming about their childhood, about the past in general, about how happy they used to be. And even us ordinary everyday Christians trying our best to live ascetical lives in accordance with the Church’s teachings, we might think back to the days before we decided to take our religion seriously—days when we went out on the weekends, perhaps had fun, drank a little bit too much, danced, maybe flirted, picked up someone, took them home, maybe went to the clubs, maybe did some drugs. Maybe we think about what it was like when we were at university, meeting new people. It was so exciting reading books, going to the student union, talking about things, exchanging ideas, debating. Maybe if we’re middle-aged or even old-aged, we think back to when we were healthier, younger, when our muscles were stronger. Perhaps we were more sexually attractive, how fun that was, how nice that felt.

I think we can all find ourselves attacked by these sorts of fantasies. And what does Evagrius say? What is the demon’s intention? What strategy is the demon of sorrow pursuing here? He lures you into fantasizing nostalgically about the past, about all the past pleasures you used to enjoy. He lures you first into fantasizing about them more or less innocently. You’re just happily recollecting the pleasures. And then he throws at you the idea that you’ll never have these things again so long as you pursue the Way of the Cross. The Way of the Cross is getting in the way of you enjoying all of these innocent, pure pleasures. The pleasures of friends, of family. The Way of the Cross is the problem!

He attacks you with these thoughts, reminding you that because of religion you’ll never have fun again—and so you are plunged into sorrow. Your soul becomes wretched. And out of sorrow, depression, melancholy, you allow your commitment to religion to decline, to wither away, and die.

So, Evagrius says the demon launches a two-pronged approach. First, logismoi scattering the mind, he says, scattering the mind with memories of pleasure. And second, logismoi that contract the soul, humbling it with sorrow. That’s the dynamic. The point being really that what we must be on the lookout for is that first prong. Those first logismoi of nostalgia—of thinking about our childhoods, our past, when we were, so we think, happier. That’s what we should be on the lookout against. That’s what we should avoid.

Now, he doesn’t mention it here, but I think linked to this—to sorrow here—is envy. And in fact, in the West, envy would become the deadly sin that replaced sorrow. I think there’s a certain wisdom in that. Envy is a much more specific passion than sorrow. And as we’ll see in a second, Evagrius’s system here is slightly messy because he splits sorrow into two, but the second half of sorrow is what he calls the demon of wrath. So envy, I think, does work a bit more. And envy works the same way as Evagrius has said sorrow works here. Envy doesn’t necessarily make you think of the past, but for those of us in the world, envy is a one-way ticket to sorrow, to melancholy, to depression.

People who are addicted to Instagram especially know this very well. Instagram apparently is the most psychologically corrosive social media app, and it is based on envy. You scroll through the app seeing pictures—finely curated pictures of people living their best lives. And the whole time, underneath the demon is whispering to you, you don’t have that life, you deserve that life and yet you don’t have that life, shouldn’t you have that life? Chipping away at your sense of yourself, plunging you further and further into a kind of mindless sorrow and melancholy. Depression, as we call it.

So that’s sorrow and envy. Next: wrath.

Chapter 11.

Wrath is a very quick passion. It is described as a boiling and a movement of anger against someone who has committed an injustice or who is thought to have committed an injustice. It makes the soul savage all day long, but it especially seizes the nous during prayers, bringing into view as in a mirror the face of one who has caused him sorrow. Sometimes, when it lingers and transforms into rage, it causes disturbances in the night, the wasting of the body, a pale appearance, and attacks by venomous beasts. (But these four things, which accompany wrath, can also be found accompanying many logismoi.)

So that’s wrath. Very straightforward. We’ve all felt it. We know exactly what wrath feels like.

Evagrius calls it a movement of anger against someone who has committed an injustice or who is thought to have committed an injustice. That word translated anger there is thymos, and thymos is the natural energy of the thymikon, the second part of the soul, the irascible part of the soul. And in fact, as we’ll learn in the next episode, thymos, anger, is a natural power of the soul, though it is unnatural to direct anger against another human being.

I think it’s instructive that Evagrius links wrath to a feeling of injustice, whether valid or not. Wrath in this sense is linked to vengeance. And if scrolling through Instagram is a one-way ticket to envy and therefore to the first kind of sorrow, the kind that comes from the deprivation of desires; well then, wrath and vengeance can perhaps be linked to something like Twitter, or to the news. When there paraded before you are all the injustices in the world, making you angry, making you thirst for vengeance, and eventually making you collapse into depression. That’s the other kind of sorrow, the kind that follows upon wrath.

So, we must all be on the lookout for that as well. And we would do ourselves a huge service by ignoring the news completely, now and forever, world without end! But I don’t suppose we will. It’s very hard to tear your eyes away and yet it is a very sinister and insidious thing, the news. Twitter. All of this wrath, all of this vengeance everywhere.

Now, one other thing to point out here is that Evagrius says that wrath especially seizes the nous during prayer. He’s very specific here. He says that when you try to pray, suddenly you see in your mind’s eye the face of someone who has caused you sorrow. That means someone who has insulted you, someone who has irritated you, annoyed you, someone who has inspired any kind of wrath inside of you, whether that’s a fiery wrath, a cold critical wrath, whatever the tenor of the wrath, if you have succumbed to it in your normal life, then when you sit down to pray, the face of that person will get in your way. ‘Do not let the sun go down on your wrath,’ St Paul says. And Christ himself in the Gospel, remember he says, if you’re on your way to the altar and you realize you have something against your brother, then go, make it up with your brother, and then come and bring your gift to the altar. Well, the altar of the mind is the greatest of all the altars, and when we stand before God at prayer, we are bringing our gift to the altar. We must not do so if we are harbouring wrath, resentment, or vengeance against someone, because the face of that person will appear in our imaginations and pollute our prayer.

Fascinatingly, Evagrius says that it could also lead to being attacked by venomous beasts. I think that might be a monkish dimension of wrath. I’m not sure if normal people like us are ever attacked by venomous beasts because of our wrath. Although you never know. I mean, sometimes people are attacked by wild animals, bitten by dogs, scratched by cats. Who knows? Maybe underlying all of that is a soul that has succumbed to too much wrath, and it manifests on that level. Although in fact, Evagrius says that attacks by venomous beasts can be found accompanying other logismoi, not just wrath. So whenever you’re bitten by a rabid dog you can stop and think, which logismos have I allowed into my mind that led to that happening?

Okay. Next, acedia or sloth.

Chapter 12:

The demon of acedia, who is also called the noonday demon, is the heaviest of all the demons. He attacks the monk around 10 a.m. and besieges his soul until 2 p.m. First, he causes the sun to appear slow-moving or even motionless, making the day seem fifty hours long. Then he constantly compels him to glance toward the windows, and to rush out of his cell, to gaze at the sun, to see how far it is from 3 p.m., and to look around here and there to see if any of the brothers are present. Furthermore, he instils hatred toward the place, toward life itself, and toward manual work. He also suggests that love has disappeared from among the brethren, and that he has no one to console him, and if during those days someone happens to have caused the monk sorrow, the demon adds this as well, to increase his hatred. He also leads him toward a desire for other places, where the necessities of life can be found easily, and where one can conveniently pursue a more successful craft. Moreover, he adds that pleasing the Lord does not depend on any particular place, for, he says, the divine is to be worshipped everywhere. He adds to these things the memory of relatives and of the former way of life, and he portrays the span of life as long, bringing before his eyes the labours of asceticism, and, as they say, he stirs up every possible device, so that the monk, having abandoned his cell, might flee the contest. No other demon immediately follows after this demon. Rather, after this struggle, a peaceful condition and an unspeakable joy takes over the soul.

Okay, that’s a long chapter, and there’s no need to go over that in detail. It’s very clear. I think we all know exactly what that feels like. Something like boredom that grows into a kind of agitation. Desperation to just do something, anything apart from what we’re supposed to be doing, which is so damned boring—our discipline, our work. When the day seems to last forever. And in that state of increasingly tetchy boredom, you start ruminating. You start remembering the people that you don’t like, the people who have annoyed you, the people who have mistreated you. Where you start thinking about moving house, going somewhere else, starting a new life. Your whole religious life becomes distasteful and boring. And the thought arises, you know, why all this asceticism? Why are you trying so hard? Doesn’t God love you? God is love, isn’t he? And God’s everywhere. God’s not just in the Church, he’s not just in your prayer corner, he’s everywhere. Go for a walk, go to the nightclub even. God’s there too, isn’t he? Isn’t God everywhere? These sorts of thoughts, all trying to get you to give up. To stop practicing your religion.

This is sloth, acedia. It’s a very, very insidious demon. A very hard logismoi to combat and tends to attack a soul for a long time. If you’re of a depressive or melancholic nature, if you feel low energy, lazy a lot of the time, it’s extremely possible that the demon of acedia, of sloth, is attacking you. It’s a difficult fight. It can last, as I say, a long time.

The good news at the very end, Evagrius says, after the struggle, when the demon withdraws, a great feeling of peace follows and even, he says, an unspeakable joy. So that’s something. Unlike these other demons we’ve talked about so far, sloth is a sort of climax demon, and once he leaves, you’re usually granted a respite for a while. It’s a wonderful feeling.

And in fact, I’ll point out, as I’m sure you noticed, that the demon of acedia in a way is combining all of the logismoi that we’ve already mentioned. So, it says here that acedia is actually building on wrath. So acedia is using a lot of the same logismoi that the demon of wrath was using—and in fact is harnessing wrath as well. Which suggests, and I think Evagrius would more or less say this is the case, that acedia only attacks the soul if that soul has given itself over to wrath already. Just as wrath only attacks the soul if the soul has already given itself over to sorrow. And similarly, sorrow won’t really attack your soul unless you’ve already succumbed to avarice. And so on. So, there’s a kind of ladder, really, of these logismoi, of these demonic temptations. And acedia here is taking up where the demon of wrath has left off. And the kind of sorrow that follows upon wrath has infected your soul, then you’re in the perfect position for the demon of acedia to attack you.

Okay, just two more. Next, Vainglory.

Chapter 13:

The logismos of vainglory is exceedingly subtle, readily approaching those who are successful in virtue, aiming to publicize their struggles and hunt after the esteem that comes from men. It fabricates demons crying out, women being healed, and a crowd touching the hem of one’s garments. It even prophesies priesthood for him in the future, and places before him people at his door seeking him, ready to take him away in chains, even as he pretends to resist. Having thus lifted him high on empty hopes, it then takes flight, leaving him either to the demon of pride to tempt him, or to the demon of sorrow, who introduces logismoi contrary to his expectations. Sometimes it even delivers into the hands of the demon of fornication the one who was just now in chains and being led off as a holy priest.

I must say, reading that description of the demon of vainglory makes me feel particularly ashamed of myself. Because I cannot tell you the amount of times I have caught myself fantasizing about precisely these things. Becoming a great priest! A miracle worker! I love this, it fabricates demons crying out as if as if this guy is casting out demons. Women being healed! And what I love about this is after you’re fantasizing about people forcing you to become a priest and you’re standing there going, ‘No, no, no, no. Not me. I’m not good enough. Oh, all right. If you say so. Okay, you’re forcing me. Okay, I’ll become a priest!’ After this, it raises you up and then just dashes you down by making you think, ‘No one sees how great a priest I would be!’ So you’re really depressed.

Or, I mean, this is the worst, when it says, even at the end of all of this madness, suddenly you’ll be overwhelmed with the demon of fornication. So the guy who was a minute ago fantasizing about being dragged off, acclaimed as a priest, is suddenly attacked with very vicious fornication.

You know, and frankly—this is to be a bit serious now—vainglory is a passion of soul that tends to attack clergymen especially. For obvious reasons perhaps. And maybe this is therefore an explanation why so many priests find themselves implicated in all sorts of salacious fornication.

And once again we ask ourselves why. What is the logismos eventually aiming at? It’s a strategy to plunge the soul into despair, to convince the soul to give up. And so the demon of vainglory is building you up, puffing you up, giving you these fantasies, these indulgent fantasies of you being a great saint, a great preacher, a great priest, maybe even the Pope. You know, these big fantasies. So that plunging you into sudden and overwhelming fornication, you will be cast into despair, give up and possibly even kill yourself.

So, you know, I was laughing before because it’s all so personally shaming. But it’s a serious demon. Anyone who embarks upon the spiritual path, anyone who takes religion seriously, must be on his or her guard against the demon of vainglory and these sorts of logismoi. They will be very familiar to you. I know they will. You must resist them. You must pray for me that I resist them too. These logismoi are a real menace.

Okay, finally, the last of Evagrius’s eight primary logismoi: pride.

Chapter 14:

The demon of pride becomes the cause of the soul’s most grievous fall. For it persuades the soul not to acknowledge God as its helper, but to consider itself the cause of its successes. And to be puffed up against the brethren, as though they were stupid because they do not all share the same high regard for him. Following close behind are anger and sorrow, and in the end, the greatest evil: a derangement of the mental faculties, madness, and the sight of a multitude of demons in the air.

Terrifying stuff! Pride.

A lot of people wonder, what’s the difference between vainglory and pride? But there’s a big difference. Vainglory is a demon that convinces you that you’re great stuff. Pride is the demon that convinces you that whatever you have that is good is from yourself and not from God. It’s conceivable that a vainglorious man would still believe that his glory came from God. A prideful man has forgotten God altogether and when he looks at his virtues, at his intelligence, at all of his good qualities, he attributes them to himself.

Now, the picture that Evagrius paints here is of someone in great self-delusion. When he says that pride makes a man think that other people are stupid because they can’t see just how great he is. Like before, anger and sorrow are there, ready to cast the soul into depression and despair. But then, worst of all, the degree of self-delusion is such that it leads to real madness, and even, Evagrius says, visions of demons in the air. Now, this might be a terrifying vision, and there are stories from the Desert Fathers of men in terror jumping off cliffs to their death. Or it could be a wonderful vision of demons masquerading as angels of light, inflating the man’s self-esteem even more, plunging him into ever greater extremes of pride.

Pride is terrible. It’s the last of the eight demons. And though yes, the demon of pride attacks you, let’s say, at the end of your spiritual life. But the of pride, the passion in the soul that this demon is trying to set in motion with his logismoi, that passion is in all of us. Pride is there at the bottom of ourselves, in that inner hell, deep, deep down. We are to some degree all already in that self-delusion. We all already live more or less unconscious to the reality of God’s omnipresence and therefore ungrateful for all the blessings that we have received from him, unconsciously attributing to ourselves what really are all gifts of God. We are all dogged by simmering resentment against people, feeling quite sure that they don’t see us for what we really are, that they don’t give us the regard we are due. And so there’s often this underlying sorrow, this low-energy depression that just nips at the back of our minds, draining the meaning out of life, making us feel that nothing really has any ultimate point, slowly but surely leading us into despair, into deceit, into madness.

These days there’s a lot of talk about personality disorders on the Internet. Narcissism is a very popular word. Sociopathy. The dark triad traits. It’s like our culture is obsessed with the kind of derangement, the kind of madness, the monstrous degree of self-deceit, of self-deception that comes from succumbing to the passion of pride. We must all be on our guard against this particular demon, and we must all in humility seek out the pride that is there inside of us and repent of it.

And on that gloomy note, that’s the end of this episode of Life Sentences. We properly met St Gregory the Theologian when we stood alongside Evagrius in Constantinople and heard the great saint reveal something of his inner illumination to us. And Evagrius walked us through the eight primary logismoi, the eight basic demonic stratagems that the demons pursue, trying in almost every case ultimately to get us to give up the spiritual life. To stop walking the Way of the Cross. To leave the narrow road that leads to life and to join instead the broad path that leads invariably to death. We must not do this. We must be on our guards, cultivate inner attentiveness, listen for the voices of the demons in our heads, listen for these eight logismoi, these eight mental stratagems, these eight temptations trying to subvert the natural order of our souls, so that our rational minds are subjected to our powers of desire and anger in pursuit of pleasure.

Let’s be on our guards, let’s walk the Way of the Cross with intelligence, yoking our minds always to prayer, keeping our inner eye always watchful.

I hope you have enjoyed this episode of Life Sentences. If you have enjoyed it, and if you haven’t already, please do consider taking out a paid subscription to the podcast. It does take a lot of work to prepare these episodes. I can’t tell you what a challenge it is to translate passages from St Gregory the Theologian. His Greek is very difficult, as is his thought. Certainly, Evagrius isn’t easy either. I’m doing my best to understand it and to present it to you in terms that we can all understand. As I say, I hope you appreciate it. Please do take out a paid subscription if you can. I could really use the help.

And if you have taken out a paid subscription, allow me once again to say thank you. I really appreciate the help.

Next time we will continue going through the Praktikos, when Evagrius, having told us about the eight primary logismoi, will tell us how best to combat them.

Until then, stay well.

Share this post