What follows is a complete transcript of this week’s podcast episode, which you can listen to in the Substack app or via your preferred podcast platform.

The podcast is designed to be listened to, so I encourage you to listen. But I’m also providing transcripts, as you may want to read along as you listen.

Welcome to Life Sentences, an exploration into the wisdom of the ancient Church Fathers presented by me, Thomas Small.

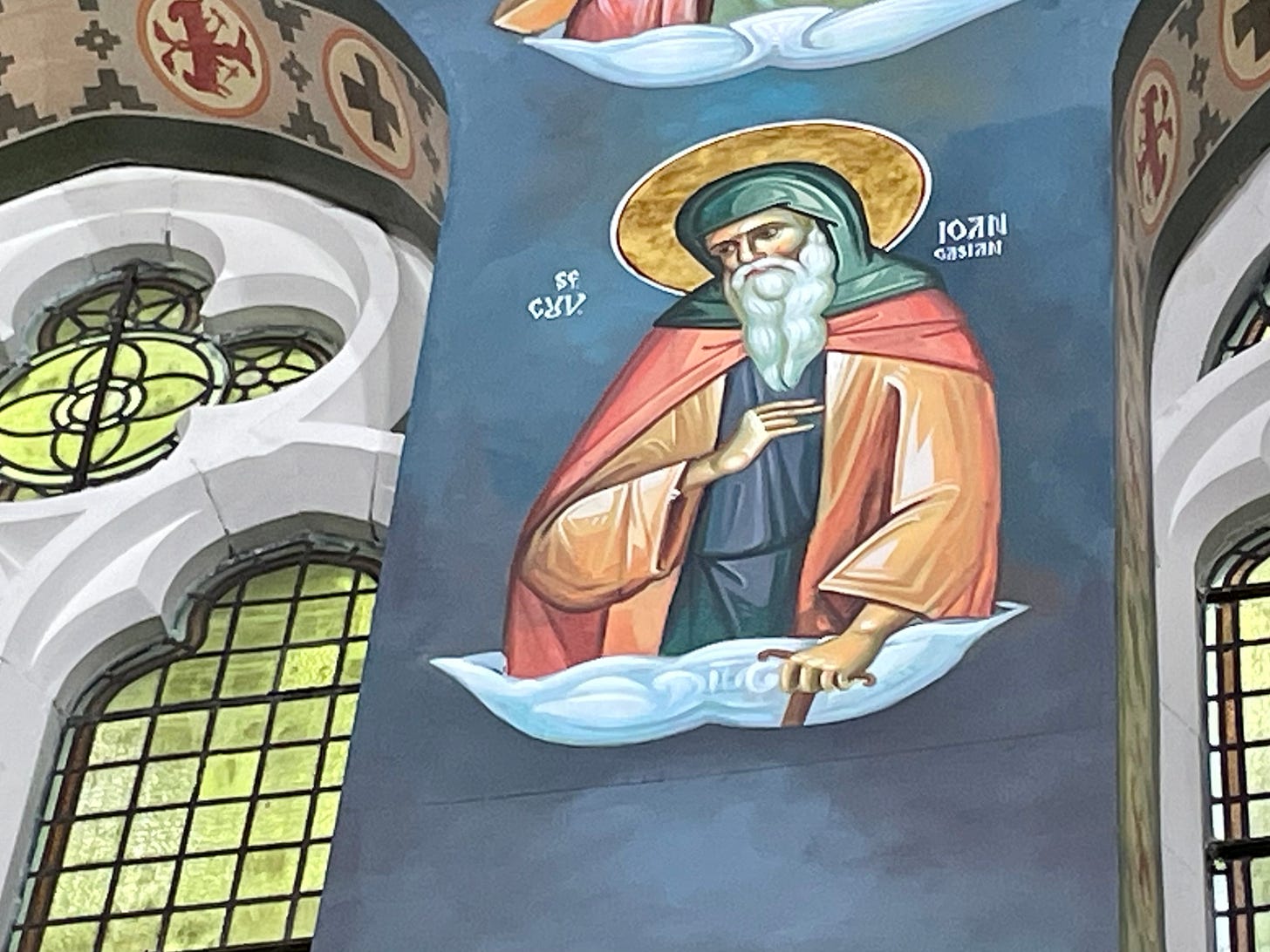

In this episode, we continue our way through St John Cassian’s interview with the great Egyptian ascetic Abba Moses the Black, who shifts his focus from the goal of purity of heart to the ultimate end: the kingdom of God.

Right, in the last episode we met St John Cassian who introduced us to Abba Moses the Black. Abba Moses was very careful to distinguish between our ultimate end, the kingdom of God, for which we should be willing to sacrifice everything, and our proximate goal, purity of heart, which is what we need to stay focused on. We don’t focus on the kingdom of God, we focus on purity of heart. And all our spiritual practices are only useful to the extent that they help cultivate purity of heart. In themselves they are nothing.

In this episode, Abba Moses will continue sharing the wisdom of the desert with St John and his friend St Germanus. However, before we resume their discussion, as promised I think I’d better present a bit more of St John’s life story.

When trying to tell Cassian’s life story, we have to reckon with the paucity of sources. He does talk about his life in The Conferences, his great work, but what he says is lacking in detail and the first independent written account of his life, written down a few decades after his death, has been called into question by modern scholarship.

So what I said in the last episode, that he was born circa AD 360 in the province of Scythia Minor along the Black Sea coast in what is now Romania, that is very much a traditional account—though that very first biographical sketch of Cassian’s life, written by a monk named Gennadius who lived in one of the monasteries near Marseille that Cassian set up—Gennadius describes Cassian as natione Scytha, meaning ‘of Scythian nationality’, and to modern-day Romanians, John Cassian is considered very much one of their own. He was a Dacian, they say, of whom they consider themselves descendants.

He was certainly a native speaker of Latin, though it is very likely that Cassian was raised to know Greek, especially as he was from a wealthy Christian family with a large estate, according to scattered references in his own writings. Cassian must have had a good classical education because his writing style is good, if convoluted, and peppered with literary allusions, and this meant that relatively uniquely he was completely fluent in Latin, his native language, and Greek. This is why he could play the role that he did, translating the ascetical wisdom of the eastern deserts for the western Latin-speaking world.

Now, according to tradition, he entered a monastery as a teenager in the ancient city of Tomis, the capital of Scythia Minor, which is now Constanța in Romania. This is slightly unbelievable because it’s not likely that there were organized monasteries in that part of the Empire as early as that, but who knows.

Certainly in around 380, he makes the journey to Palestine and joined a monastery in Bethlehem.

Let’s talk a little bit about Bethlehem. Then as now, Bethlehem was a small town south of Jerusalem containing the sacred cave in which, according to tradition, Christ was born.

There’s an interesting story about that cave. In the 130s AD—so 250 years before John Cassian moved to Bethlehem—the Emperor Hadrian crushed the last great Jewish uprising against the Roman Empire, the Bar Kokhba Revolt, and he put it down with extraordinary brutality. An estimated 600,000 Jews were killed and basically all of Judea was ravaged. It marked a huge turning point in the history of the world, really. Hadrian was determined to wipe out every trace of quote-unquote Jewish superstition in Judea and in his mind this included Christianity. He renamed the province Palestine to remind the Jews of their ancient enemy the Philistines, and over the ruins of Jerusalem he erected a new pagan city which he called Aelia Capitolina from his own family name Aelia and from the Capitoline Jupiter, the Roman God who had vanquished the Jewish God—or so Hadrian falsely believed—and whose cult was implanted atop the ruined Jewish temple. Over the site of Christ’s tomb in Jerusalem, Hadrian built a temple to Venus, a move clearly aiming to invert Christian morality, which emphasized chastity, and which policy he imposed on Bethlehem as well, for inside the Cave of the Nativity he established a shrine to Adonis, in myth the lover of Aphrodite, who incarnated the Greek ideal of erotic male beauty, to which ideal Hadrian himself was a devotee. (He’d elevated his own teenage lover Antinous to the status of a god.)

But that was ancient history by the time John Cassian arrived. The Emperor Constantine had cleansed the cave of the Adonis cult and built an enormous basilica over the cave, and with some additions following a fire in the 6th century, that basilica still stands there today.

Now remember, Cassian went to Bethlehem with his childhood friend St Germanus. ‘I was so closely befriended with Germanus,’ he would write, ‘from the very time of our basic training and the beginnings of our spiritual soldiery that everyone used to say we were one mind and soul inhabiting two bodies.’

Note the intensity of brotherly love. It’s good to keep that in mind because ascetical writers like St John so emphasized detachment and dispassion that you’d think they had no feelings for others, no love, but that is untrue. They can love more powerfully than we can precisely because they have purified their hearts of passionate attachment. They love with the love of God.

Cassian and Germanus, these two great friends, became members of a monastery near the Cave of the Nativity. Later on, Cassian would be rather critical of this monastery. He said the monks were overly fond of sleep, so much so that a new divine office had to be devised to ensure that they stayed up at night. (Was this perhaps the origin of what’s called the Midnight Office today? It’s possible.) Perhaps surprisingly, given their love of sleep, the monks were weirdly, overly fond of fasting, to which they adhered rigidly, refusing to lighten it even in order to offer visiting guests hospitality. Cassian believed his fellow monks in the monastery had failed to strike the right balance.

Now, one day an Egyptian monk arrived in the monastery and was assigned to live inside the cell that Cassian shared with Germanus. Back then monks rarely lived in separate cells, but were in cells of two or three, working out their salvation together. This new arrival, who was not young, was called Pinufius, and he was full of stories of the Egyptian desert. Cassian pestered him for information, and in time it was revealed that Pinufius had in fact been the abbot of a celebrated coenobium in Egypt, which he had fled in order to preserve his humility. Eventually the monks who had been under his care, tracked him down and dragged him away from Bethlehem, back to Egypt.

Cassian and Germanus’s monastic ambitions had been re-inspired by Pinufius, and after his forced departure, they were left with a great thirst for Egyptian wisdom. Inside the cave of the nativity, they made a solemn vow that they would do whatever it took to make the journey to Egypt. They secured a blessing from their abbot for a short tour of the Egyptian monasteries. This tour would last seven years.

The fruits of that seven-year tour would ripen many decades later, when John Cassian would write down his memories of the conversations he had with great Egyptian Fathers in a work known as The Conferences. Now, we are going to continue our exploration of Conference No. 1 with Abba Moses the Black and we’ll save the rest of John Cassian’s life story for the next episode or indeed the next two or even three episodes. We will be staying with John Cassian for a while. He has so much to teach us.

And just a reminder, like before I have edited the text, not so much for content, but simply to streamline Abba Moses’s presentation a bit. Long passages, especially, in which he strings together biblical quotes, I’ve taken those out. And bits that I think are important, I will summarize, just to make sure that it’s all clear.

And so let us now return to Abba Moses the Black and John Cassian’s Conference No. 1.

If you remember, when we left off last time Abba Moses had just narrated the tale from the Gospel of Mary and Martha. And he had said that Martha symbolized practical activity of all kinds, spiritual kinds mainly—fasting, doing the daily offices, reading the scriptures, providing hospitality to visiting brothers, all acts of charity performed with the body, that’s Martha. Whereas her younger sister Mary, sitting at the feet of the Lord, listening to his teaching, focused entirely on him, symbolized contemplation and therefore purity of heart—which Abba Moses says is what we should all focus on as our proximate goal, but also he said that what Mary symbolizes, purity of heart and contemplation, will not be taken away from her, but that what Martha symbolizes, all those practical spiritual disciplines, will not abide.

Germanus then says,

‘We find this surprising. Can we really say that our efforts at fasting, our diligent reading, our works of mercy, of justice, and hospitality will be taken away from us and not endure? Especially when our Lord promises a reward in the kingdom of heaven to those who do such things?’

To which Moses replies:

‘I did not say that the reward of a good work will be taken away. It is the activity itself that will be taken away, anything we do to meet bodily needs or from the frailty of the flesh or the injustices of the world.’

Now right away there you can see what John Cassian is doing. Germanus’s question was slightly idiotic. It’s pretty clear what Abba Moses had been saying, that Mary’s purity of heart and activity of contemplation would endure forever—indeed into the afterlife, as Abba Moses will go on to explain—whereas Martha’s acts of charity will not go on forever. You cannot take your acts of charity with you into the afterlife. And yet Germanus pretends or is portrayed here as not understanding that. But I think that St John is just trying to really emphasise how easy it is or can be not to make these correct distinctions between spiritual practices themselves, the purity of heart that they are meant to cultivate, and the reward that comes from purity of heart: the kingdom of heaven, eternal life. So Germanus’s question is re-establishing the theme of the Conference. And Abba Moses’s answer is going to go on now once again to emphasize these distinctions, although now his emphasis is going to be not on purity of heart, but on the kingdom of God, the kingdom of heaven, the ultimate end that is our reward.

He goes on:

‘Diligent reading and ascetic fasting are indeed useful to cleanse the heart and restrain the flesh, but only in this present age, as long as “the flesh lusts against the spirit.”’

Now, that quote there from the Epistle to the Galatians—‘the flesh lusts against the spirit’—we encountered it in episode 3, and I said then that you should remember it because the Desert Fathers especially would make a big deal out of this quote. And so here it is in Abba Moses.

Now, Abba Moses is not going to interpret this verse in any great detail, but John Cassian will later on in another episode. Nonetheless, Abba Moses is going to take it for granted that in the human person, there are these two poles, the flesh and the spirit, and that they exist in tension, indeed in conflict, and that ultimately there can be no concord or peace or friendship between the two. ‘The flesh lusts against the spirit’, which is precisely why Abba Moses has said, our acts of asceticism are useful to cleanse the heart. Those acts of asceticism, what are they except a way of restraining the flesh so that the spirit might burn brighter?

And yet Abba Moses has said such ascetical practices are only useful to the extent that we have these bodies of flesh as he will now explain. He says:

‘After all, we sometimes see these things laid aside even during this present life, when men are worn out by overwork, physical illness, or old age. How much more then will they cease in the age to come, when “this corruptible must put on incorruption”, this animal body which we have now “shall rise a spiritual body”, and the flesh shall begin to be such as no longer wars against the Spirit.’

Okay, now that is a really important sentence because there’s some fine distinctions being made there. He’s quoting St Paul, who in the First Epistle to the Corinthians lays out—in sometimes a rather elliptical way—his doctrines about the afterlife, about the role that the body plays in the afterlife. So the first thing to make clear is that the body itself is not being dismissed here. The body itself is not evil. Even the mode in which the human body currently subsists, this mode which is called fleshly, is not evil. And we saw in episode 2, I think it was, that the fleshly body, for all its weaknesses, and indeed even the fact that it lusts against the Spirit, this fleshly body has been given to us as a training device so that we will learn, in obedience to the commandments of Christ, to lay down the flesh in self-sacrifice and turn towards God in the Spirit.

So even this body of flesh is not evil. In the words of St Paul, what is now ‘corruptible’, the fleshly body, ‘must put on incorruption’, precisely by laying down the fleshly body and walking the Way of the Cross. Furthermore, the teaching is that though this fleshly body—which in this passage St Paul calls an ‘animal body’ or a ‘psychical body’, a ‘soul’ body—though this fleshly body dies, decomposes, dissolves back into the elements out of which it is made, at the resurrection it shall rise a ‘spiritual body’. This is the teaching of the Church. The same body rises again. In precisely what way nobody knows. And in fact, St Paul advises we not try to imagine it. But this body will rise again, but transformed, turned into a spiritual body. And yet even here, St John has said, this spiritual body will be comprised of what he calls flesh, but flesh that will no longer war against the spirit.

I know. Unless you’re a believing Christian, this sounds incredible. Even if you are a believing Christian, it might sound incredible. The idea of a general resurrection of the dead at the end of time, when somehow, mystically, through the power of God, our bodies are reconstituted, but transformed, no longer mortal, possessing powers that we can only imagine, and in general being such as to enable the mind, the soul to experience more of reality than we currently experience, a bit like the angels (and Christ at one point in the gospel does say that we will be like the angels)—these doctrines of the Church are very hard to believe. They’re certainly impossible to situate in our current prevailing scientific—if you like, scientistic—framing of reality. For Christianity to make sense, you have to jettison that scientistic framework, to some extent at least, and be open to the possibility that there is more to the human person and therefore more to the human body than we know.

So, having said that in the resurrection the body will no longer war against the spirit, Abba Moses goes on:

‘Restraint of the body enables the first stages on our journey, not the true perfection of agape, and this is what holds within itself the promise of present and future life. And so we believe the performance of such works are necessary only because without them we cannot rise to the heights of agape.’

Remember from the last episode, agape, often translated as love or charity, is dispassionate love. That is to say true love, divine love. Love that is extremely powerful indeed, the sort of love that would lead a man to lay down his life for his friend. But a dispassionate love, a love that demands nothing for oneself and is oriented only towards the other. Abba Moses told us in the last episode that agape is synonymous with purity of heart and indeed with contemplation, and that these were our proximate goals. We are focused on attaining purity of heart, which enables contemplation, which cultivates agape, dispassionate love.

And Abba Moses, in what we’ve just read here, is in fact being very careful. He says, restraint of the body—so all ascetical practices, all bodily practices—enable the first stages on our journey, i.e. our journey towards agape, towards purity of heart, but they do not, he says, enable the true perfection of agape, which is what holds within itself, he says, the promise, that is to say, the ultimate end: the kingdom of heaven. So without purity of heart and agape, there is no kingdom of heaven. And though, yes, without ascetical practices, spiritual discipline, and all the rest, at the beginning stages especially, there is no purity of heart, nonetheless, it is not those practices in themselves that attract the kingdom of heaven. Only agape, only purity of heart, only true contemplation does that.

Now, Abba Moses goes on, in a long passage which we’re going to skip over, to argue that in fact acts of charity that we perform with our bodies are only necessary because this world is fallen. He specifies the presence in this fallen world of inequality as the primary reason why acts of charity are needed, but that, he says, in the next world, in the redeemed world, in the heavenly world, there is no inequality and therefore acts of charity will not be necessary.

And having laid out this argument, he goes on:

‘When inequality no longer exists, everyone will pass over from all this manifold, that is, active work, to the love of God and the contemplation of divine things in perpetual purity of heart.’

You see there, he’s just re-summarized the lesson of Mary and Martha. As he said, Martha, those manifold, multiple works of charity that we perform with our bodies now, will not exist in the next world when inequality no longer exists. But rather he says everyone will pass over from a world in which such acts of charity are required to, he states, the love of God and the contemplation of divine things in perpetual purity of heart. Note the threefoldness of that. Once again: love of God (i.e. agape), the contemplation of divine things (i.e. theoria), in perpetual purity of heart.

So, Abba Moses is emphasising again and again that our spiritual goal is something like a trinity. It’s a union in three. Purity of heart: virtue, not vice. Contemplation: knowledge, not ignorance. And love of God: no idolatry, nothing intervening between the soul and the divine.

He goes on:

‘Those now who feel compelled to cultivate knowledge or purify their mind have already chosen, while still living in this age, to devote themselves with all effort and strength to this end. While still in the body, they dedicate themselves to this task, in which they will abide after the corruption is laid aside, reaching that promise of the the Lord and Savior which says, “Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.”‘

So some of us, Abba Moses says—and perhaps if you’re listening to Life Sentences, you are one of those people—some of us feel compelled now, even in this body of flesh, to cultivate true knowledge and to purify our minds, to purify our hearts. And notice, and this is really interesting, he says that those of us who do cultivate knowledge and purity of mind will abide in that when this body dies. So what he’s saying is not theoretical. In his mind there’s something incredibly empirical grounded in what he’s saying. That purity of heart, and the contemplation that purity of heart enables, and the love which grows out of that contemplation, this tri-fold activity of the mind in the heart, this activity does not diewith the body. This inner noetic activity becomes the soul. Such a soul has detached already from the fleshly body, has firmly united its attention to God in love, and therefore when the fleshly body dies, this soul will seamlessly abide in that activity. Because the activity is not bodily. It is a wholly spiritual activity, wholly native to the mind in the heart, and is therefore not arrested, not paused, not stopped when the body dies.

And Abba Moses ends this by repeating that passage from the Beatitudes, ‘Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God’. And in this context it is clear that ‘for they shall see God’ means to Abba Moses the state of blessedness in the afterlife. In this life, you pursue purity of heart, perhaps being granted glimpses of God, as St Paul says, ‘as in a mirror darkly’, but so that in the afterlife you will see God in a seamless movement from one mode of life to the other, uninterrupted by the death of the fleshly body.

Abba Moses goes on:

‘Why are you surprised that these works which we have mentioned are to pass away? When the Holy Apostle tells us how even the higher gifts of the Spirit will pass away and states that agapealone will abide forever. Agape is not limited to any time, for it not only works usefully in us in this present world, but it will also remain in the future when we have cast off the burden of physical needs, operating with greater effect and splendour, untainted by any defect, but cleaving to God more closely and more intensely perpetually incorruptible.

Wow, what a description of the soul in heaven! Powerful, splendid love, he says, is going to characterise that soul. Untainted, he says, by any defect. Cleaving to God more closely, cleaving to the source of everything, to the source of love more closely, more intensely, perpetually incorruptible. Nothing but bliss, nothing but joy, nothing but union.

It’s a vision of blessedness worthy of sacrificing everything for! And after this short break, we’ll hear Abba Moses’s further thoughts on the glory of the kingdom of God, and on the shame of its opposite, the kingdom of hell.

We’re back. Abba Moses has just described the kingdom of heaven in all its irresistible, ineffable, overpowering glory. Now, Germanus, possibly inspired by this, but also clearly rather overwhelmed, asks:

‘But who is there enclosed in the frailty of this flesh who could be so continually dedicated to contemplation as to give no thought to a brother’s arrival, or to visiting the sick, or to manual labour, or to showing hospitality to visitors. Who is never distracted by the body’s needs? Tell us, to what degree can the mind adhere to the invisible and incomprehensible God? We long to learn.’

Abba Moses answers:

‘To adhere to God continually and to be inseparably united in contemplation of him is, as you say, impossible for a person who is encompassed by the weakness of the flesh.’

Well, okay, maybe a bit of a deflation there. Abba Moses has brought us right back down to earth. In these bodies of corruptible flesh, bodies which lust against the spirit, it is impossible, he says, to be continually, inseparably united with God. Okay.

He goes on:

‘But still we ought to know where we should fix the focus of our mind’s intention and to what goal we should always recall the gaze of our soul. When the mind attains this, it is glad. And when it is distracted, it sighs in disappointment. To the extent that it finds itself losing sight of this contemplation it knows itself to have fallen away from the supreme good and considers even a momentary departure from the contemplation of Christ to be a kind of fornication.’

So Abba Moses says, look sure it’s impossible while in this body of flesh to be continually united to God in contemplation. But we don’t need to be happy about it. It doesn’t really get us off the hook. It simply reminds us that we must struggle to maintain that union. Yes, it’s impossible, but the benefit lies in the struggle. If we have fixed our mind on its intention, he says—this is the kingdom of God, the ultimate end—and if we have set the gaze of our soul on the proper goal—this is purity of heart, contemplation—if this is true of us, then he says, when we realise that we have lost sight of this contemplation by distraction, when we realise that we’ve fallen away from the supreme good, we sigh in disappointment, he says.

And even worse we consider what we’ve done a kind of fornication. That’s a strong word to use, fornication, but it’s an indication of how seriously Abba Moses takes this agape thing, love. It is love. The contemplative heart is in a love affair with God. And when the mind is distracted to things that in its imagination are not God, it feels it has cheated on its lover, it has betrayed its spouse, it has fornicated.

And Abba Moses goes on:

‘When our vision has strayed even slightly from him, let us immediately turn back the eyes of the heart to him, restoring the focus of the mind’s gaze as though along the straightest line. For everything lies in the innermost recesses of the soul. Once the devil is driven out and vices no longer reign in it, the kingdom of God is consequently established within us. As the evangelist says, “The kingdom of God does not come with observation. Nor will they say, ‘Look, here it is!’ or ‘There it is!’ For truly I say to you, the kingdom of God is within you.”‘

Okay, so now everything up to this point has been prologue, and Abba Moses now is going to talk about the kingdom of God.

He says our commitment to purity of heart should be absolute, our dedication to contemplating God should be unwavering, that whenever we are distracted we must return our gaze back to God right away, and he says we do all this because everything lies in the innermost recesses of the soul. What he’s trying to make sure everyone understands here is that the kingdom of God is an inner kingdom. An inner spiritual state. An inner reality. And once we have attained purity of heart, which he characterises now as the devil being driven out and vices no longer reigning in our souls, then this inner kingdom is established within us.

And by quoting that famous saying of Christ, ‘The kingdom of God is within you’, that is to say, it’s not outside of you, as the Lord says, it does not come with observation, nor will they be able to say, hey, it’s over there, or no, it’s over there. The kingdom of God is not outside of you. It is inside of you. It is an inner kingdom. All the more reason for the focus of our noetic attention, for the focus of our nous to remain inward.

And I can say to remain inward through repentance, through metanoia, through changing the nous, turning the nous around towards God in the innermost recesses of the soul

And Abba Moses continues:

‘Now there can be nothing within us other than knowledge of the truth or ignorance of the truth, and either love of vice or love of virtue, through which we prepare a kingdom in our hearts, either for the devil or for Christ.’

What Abba Moses says there goes right back to the very beginnings of the Church, to the earliest documents of Christian spirituality that are outside the Bible, documents like The Didache, a compendium of apostolic teaching, which notoriously begins, ‘There are two ways, the way of light and the way of dark.’ And then it lists all the virtues of the way of light and all the vices of the way of the dark. This is what contemplation means. This is what purity of heart means. Embracing knowledge and absolutely refusing any ignorance. Loving virtue only and absolutely shunning all vice.

That activity, that contemplative, purifying activity is our goal, and based on our level of performance of that activity, we prepare a kingdom in our hearts, he says, either for the devil or for Christ.

And he goes on:

‘St Paul describes the nature of this kingdom, saying, “The kingdom of God is not eating and drinking, but righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit.” Thus, if the kingdom of God is within us, and that kingdom is itself righteousness and peace and joy, it follows that anyone who abides in those things is certainly in the kingdom of God. By contrast, he who abides in conflict, in injustice, and in the sort of sadness that brings death, already resides in the kingdom of the devil, in death, and in hell. By these signs we may distinguish between the kingdom of God and of the devil.’

Okay, this is actually some really tough teaching from Abba Moses here. And first, once again, by quoting St Paul, he’s emphasised that the kingdom of God has nothing to do with eating and drinking, i.e. again, nothing to do in itself with our ascetical practices or our spiritual discipline. He says, no, the kingdom of God is righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit, and that because the kingdom of God is inside us, those things must be inside us in an abiding way in order for us to be in the kingdom of God.

And where it gets really tough is how he describes the contrast, the kingdom of the devil. The devil’s kingdom, he says, is in abiding conflict, injustice or unrighteousness, and the sort of sadness, he says, that brings death. These three things, conflict, unrighteousness, and the sadness that brings death… A soul abiding in conflict, unrighteousness and that kind of sadness is in hell, he says, is in death, is in the kingdom of the devil.

That’s how we can tell which kingdom we’re in. And I can tell you, more often than not, I’m in the other one, the kingdom of hell, the kingdom of death, the kingdom of the devil. Be honest with yourself. How much conflict is there inside of you? How much tension? How much anger? How much envy? How much unrighteousness is inside of you? How often do you do what you want to do even when you know that it’s not the right thing? That’s injustice. That’s unrighteousness. And worst of all, that sadness, he says, that brings death. That solipsistic, self-centred, self-pitying sadness that is all too easily indulged.

Conflict, injustice, and sadness all together comprise the inner state known as hell. And though Abba Moses himself does not go on to say this, I will say it. Thank God that Christ harrows hell. Those of us in the kingdom of hell need Christ more than anyone else.

So first of all, take heed and, as he says, by these signs distinguish between the two kingdoms. Know which kingdom you’re in. Don’t lie to yourself and if, as frankly is likely, you’re in the kingdom of hell, repent. For the kingdom of heaven is at hand, is near, if you repent.

Abba Moses goes on:

‘And indeed, if with the lofty gaze of the mind we consider that state in which the heavenly and sublime powers dwell, who are truly in the kingdom of God, what else should that state be believed to be than perpetual and unceasing joy? For what is so proper to true blessedness and so fitting as continuous tranquillity and eternal joy.’

A description there of souls in heaven, specifically, he says, the heavenly and sublime powers, the angels, he means, those who are truly in the kingdom of God. But remember, Christ does say that in the resurrection the saints will be like the angels in heaven. And so, repent! Keep your mind focused on the goal of purity of heart, hoping for that eternal kingdom of true blessedness and continuous tranquillity and unceasing joy.

But again, don’t lie to yourself. Don’t lurch towards self-righteous self-satisfaction. Don’t pretend you’re already in the kingdom of God if you are still in the kingdom of hell. Because the kingdom in which you really are matters. It determines the state of your post-mortem soul, as Abba Moses will now say:

‘Therefore, while still in this body, let each of us be aware that we will eventually be assigned to that region or ministry to which we have shown ourselves a participant and practitioner in this life. And let us not doubt that in that eternal age we will also be a companion of the one whom we have preferred to serve and associate with now. Our Lord tells us this when he says, “If anyone serves me, let him follow me. And where I am, there my servant will be also.”

‘Just as the kingdom of the devil is embraced by acquiescence in vice, so the kingdom of God is gained by the practice of virtue and possessed in purity of heart and knowledge of the Spirit.

‘Where the kingdom of God is, be sure that there too is eternal life. Where the kingdom of the devil lies, there assuredly lurk death and hell, and those who dwell there cannot so much as praise our Lord. As the Prophet tells us, saying “The dead shall not praise you, O Lord, nor any of them that go down to hell”—that is, the pit of sin. But he says. “We that live…”—not to sin, not to this world, but to God—”...we bless the Lord from this time now and forever.” And “For no one is mindful of you in death and who shall confess you in hell?” —that is, the hell of sin. The answer is, no one.

‘For no one, even should he profess himself a Christian a thousand times over, can confess the Lord while he is sinning. No one who submits to what the Lord has condemned can be mindful of the Lord. No one can claim to be his servant whose commandments he scornfully repudiates.’

Okay, so Abba Moses is flipping back and forth here between an eschatological perspective focusing on the afterlife, on whether we’ll be in hell or in heaven after we die, and a more, let us say, psychological perspective emphasising that these kingdoms of heaven and hell are within

us even now and are really comprised of the virtue or the vice that live in us now.

So in a way, he’s saying, look, are you a Christian? Don’t think that you’re supposed to wait around to find out where your post-mortem soul will reside. Find that out now by pursuing the kingdom of God now. Because if you practise virtue now, if you strive for purity of heart now, if you cultivate knowledge of the Spirit now, then he says the kingdom of God is gained now, and after you die, you will be assigned to that region.

But the same applies with hell. Do you fail to resist selfishness now? Do you willfully indulge in pleasure-seeking and in all sorts of mental distractions now? Are you inclined towards partial knowledge of this-worldly facts now? Well then, you’re in hell now, and in hell you will be after you die.

There is basically for the soul a continuity, a smooth movement from this life to the next life, where in whatever state it is here, it will remain in there, so get it right here.

And again this shift in perspective from the eschatological to the psychological informs the way that he’s playing with the idea of death here, by weaving together those different quotes from the Psalms. ‘The dead shall not praise you, O Lord, nor any of them that go down to hell.’ And then Abba Moses interjects, ‘that is, the pit of sin’. ‘For no one is mindful of you in death,’ the Psalm says, ‘and who shall confess you in hell?’ ‘That is,’ Abba Moses says, ‘the hell of sin.’

Abba Moses wants you to know that hell is sin. Heaven is virtue. And therefore, he says, even if you call yourself a Christian a thousand times over, if you are sinning, then you are not confessing the Lord. You are not praising the Lord. You are not witnessing to the Lord. Which is in fact what the soul is meant to do. This is the highest, most sublime activity of the mind: loving, ecstatic, joyful praise of God. This is the activity of the angels, but this activity is fraudulent in the soul that is sinning, in the soul that is truly dead, even if its body is alive.

As Abba Moses now says:

‘This is the death in which the apostle declares the luxurious widow to lie, saying, “She who lives in pleasure is dead while she lives.” And there are many who are dead while living in this body. They lie in the pit and cannot praise God. Whereas there are many who may be physically dead but praise and bless God in the spirit as in the text, “O spirits and souls of the righteous, bless the Lord!” And “Let every spirit praise the Lord!”

So there you have it again. You think he’s emphasising the psychological perspective, saying that hell is sin, heaven is virtue, get your inner state right, it’s all about an inner state. And then he immediately switches to that eschatological perspective and says that just as people dead in their sins now while alive in their bodies cannot praise God, so are people dead in their bodies but alive in their spirit praising God. So St John Cassian is not interpreting what we might consider to be mythological materials in a psychological way. Not at all. He absolutely assumes the objective reality of otherworldly life, of heavenly life, of the soul as a different substance from the body, of the spirit able to abide beyond death in heavenly realms. He takes all of this absolutely for granted, as does the Christian Church.

And the psychological dimension now is a concomitant of that other dimension. Because the soul is immortal. The soul does not die. Even the sinful soul now in the body, once the body is dead, that sinful soul will not die, in the sense it will not cease to be. It will continue to be, as a soul now separated from the body, still in its sin in hell.

So we mustn’t interpret away the eschatological or spiritual dimension and say it’s all just symbolism for psychological realities. No, no, the psychological realities and the eschatological realities are one because the soul is immortal. As Abba Moses now will definitely make clear.

He says:

‘The gospel parable about the poor man Lazarus and the rich man clothed in purple shows us that we are not idle after separation from the body nor unconscious.’

If you are not familiar with that parable, then go and read it. It’s in Luke, chapter 16. The parable starts on earth. There’s a rich man enjoying himself in his mansion, and a poor man named Lazarus outside the mansion begging bread, but the rich man can’t be bothered to give him any. Then they both die and in the parable are portrayed: the rich man in Hades and Lazarus, the poor man, in the bosom of Abraham. And Abba Moses has said this parable makes it plain that our souls are not idle, they’re not insensate, they don’t cease to exist after their separation from the body, nor are they unconscious.

And he continues:

‘For Lazarus found rest in a place of bliss, namely the bosom of Abraham, and the other was tormented in the unbearable heat of eternal fire. But also this, if we’re happy to consider it, which was said to the thief, “This day you shall be with me in paradise.”‘

Here he’s referring to the good thief crucified alongside Christ, who recognized Christ as the Messiah, in exchange for which Christ said that ‘This day you shall be with me in paradise.’

Abba Moses goes on:

‘What else does this obviously signify than that not only the original intellects endure in souls, but also that they, in accordance with the fitting recompense for their merits and actions, enjoy the corresponding quality.’

That is a really weird sentence. It is one of the places, and this sometimes happens, where St John Cassian lets slip some of the more hidden mystical doctrines of the Egyptian desert, indeed some of which were later on condemned by various Church councils. These are doctrines associated with the third-century Church Father, Origen, and the late fourth-century Desert Father, Evagrius of Pontus, who was in fact John Cassian’s teacher. I can’t go into that now. Maybe as Life Sentences proceeds, I can explore more of this dimension of the Christian tradition. But for now, signs of this more mystical, speculative, metaphysical, let us say, dimension of the desert can be seen in what St John has said here: ‘the original intellects endure in souls.’

So remember, St Leo and St Basil made it clear that what you are is a mind, a nous, and that in some sense—precisely what sense is impossible to determine—the mind that is you is somehow eternally in the mind of God. That is to say, before your creation the person you are, the mind that you are, was somehow in the mind of God, and that at your creation, that mind, who you are, was given a body, and that possessing a body is what it is to be created. God alone is without a body, bodiless. Anything created possesses a body because embodiment is what createdness is. So in some sense you were an ‘original intellect’ and in Latin intellectus is the translation of nous, of mind in this sense. And so that original intellect that you are was created, given a body, and that the glue between the mind that you are and the body that you were given, the glue between the two is the soul. The soul animates the body, gives life to the body, while also mediating to the body the mind’s powers and influences. And vice versa, what the body perceives through the senses is mediated via the soul to the mind.

And Abba Moses has said that the parable of the rich man and Lazarus and what Christ said to the good thief on the cross, ‘This day you shall be with me in paradise’, Abba Moses says that these signify that ‘original intellects endure in souls’, which isn’t saying anything that he hasn’t already stated. There is life after death, the body dies, the soul remains alive. But it’s the way he’s put it here, the original intellects endure in souls. Almost like the soul is the body of the intellect and the body is the body of the soul.

Something like that. These are complicated, speculative matters. And as I say, down the line, these speculations would get some people in trouble with the Church. And so here I’m just trying to explain what Abba Moses is saying and certainly what he’s also saying is that there is divine justice. There is what he calls a fitting recompense in the afterlife for our merits and actions in this life. If you want to think of karma here, go for it. It’s a bit like karma. What you do now does determine the state of your soul then.

But also, all of this shows that the soul survives the death of the body. The mind survives the death of the body.

Αs Abba Moses says:

‘These passages clearly show that the souls of the dead are not deprived of their perceptions, nor even of their affections, namely hope and sorrow, joy and fear, and that, to some some extent, they begin to have a foretaste of what is destined for them in the General Judgement.’

That’s a reference to the Church’s doctrine that at the death of a particular soul, your body dies, your soul proceeds into the next life, and that this is before the General Judgement. Which is to say, this is before the resurrection of the body from the dead and the final judgement of all souls. Between your death and that general judgement, he’s saying, the soul exists in some state, not deprived of its perceptions nor its affections, and will have some experience of what that ultimate judgement will be. So again, if you die in a state of sin, before the general resurrection, your soul will be in a state of torment, whatever that means. If you die in a state of purity of heart, your soul will be in a place of bliss, whatever that means. That’s what he’s saying.

And he goes on:

‘Contrary to the opinion of some sceptics, souls are not dissolved into nothingness after passing from this life, but enjoy a fuller life and apply themselves more fervently to the praises of God. Is it not the height of stupidity, indeed even madness, to entertain the lightweight opinion that the more valuable part of man, in which, as St Paul tells us, the image and likeness of God reside, could become insensible after laying down this bodily burden in which it is presently confined? It is the element which contains in itself the whole power of reason, and just by inhabiting it is capable of giving perception to the dumb, unfeeling stuff of the flesh. Far more logical it is, and more in accordance with the nature of reason itself, to suppose that once the mind has shuffled off the gross flesh which now hinders it, it can exercise its intellectual abilities even better, and far from losing them, receive them in a purer and more refined state.’

Now I can’t pretend there that Abba Moses has presented some cast-iron argument in favour of Christian doctrines on the afterlife. Obviously he has not.

But then it’s worth spending a little bit of time on. He’s talking about the mind, which he calls ‘the more valuable part of man’, more valuable than the body. He says that it is in the mind that the image and likeness of God resides in the human being. He makes that clear. But he says that the mind contains the power of reason and by inhabiting the body it is the mind, he says, that gives perception to the flesh.

This is the opposite of what we believe now. We think that our minds, which we tend to consider to be simply epiphenomenal delusions created by a purely mechanical neurological process in our brains, that our minds are receiving perception from the flesh, from our senses, that it is our bodies that are in fact perceptive and that those senses pass perceptions to the mind via the brain. St John Cassian or Abba Moses is characterising it in the reverse way. That it is the power of reason which resides in the mind, understood as a spiritual substance essentially different from the body, that inhabits the body and grants to the flesh its powers of perception. It’s the other way around.

And in fact, Abba Moses then says, precisely because it inhabits this gross, essentially unfeeling fleshly body, that the mind’s intellectual powers are in fact less now than they would be if the body was notfleshly, or at least in a different mode of fleshliness. And that once this gross flesh has been shuffled off, the mind will actually know more. It will operate more purely, more perfectly.

Which reminds me of that metaphor that I came up with in an earlier episode, where the fleshly body is like Luke Skywalker’s masked helmet. It actually is limiting the mind’s ability to see, precisely so that the mind would learn how to have faith, would learn to remain turned to God even when he cannot see him.

I’m not well versed in the philosophy of mind or in the latest researches into questions of neurology and consciousness and things like that. I have read a certain amount about it. What I have read has convinced me that the way people are now encouraged, without really thinking about it, to imagine the relationship between the body and the mind and perception and reason is not nearly as straightforward, in fact, and that the science is rather inconclusive at the moment, and arguments—very strong arguments, from what I can tell—suggest that maybe Abba Moses’s conception of the mind being a principle separate from the body, that is in fact what gives the fleshly body its powers of perception, that that might in fact be the case.

Abba Moses certainly thinks so and he goes on:

‘St Paul recognizes that what we have been saying is true, for he himself longed to depart from this flesh, so that liberated from it he could be more closely united with his Lord, saying, “My desire is to depart and be with Christ, for that is far better.” And, “We know that while we are at home in the body, we are away from the Lord.” So that, “We are of good courage, and we would rather be away from the body and at home with the Lord. So whether we are at home or away, we make it our aim to please him.” He is proclaiming that the soul’s sojourn in this flesh is a pilgrimage away from the Lord and an absence from Christ, and is declaring with full faith that separation and departure from this flesh is to be in the presence of Christ.

More clearly, on the same point of the richness of the life of the soul, the Apostle continues, “You have come to Mount Zion and to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem, and to innumerable angels in festal gathering, and to the Church of the firstborn who are enrolled in the heavens, and to the spirits of the righteous made perfect.” In another place he refers to these spirits: “We have had earthly fathers who disciplined us and we respected them. Shall we not much more be subject to the Father of spirits and live?”‘

So Abba Moses is really encouraging us to take seriously the Church’s teaching on the soul, on the substantial reality of the soul, on the fact that the soul survives the body, the soul is immortal whereas the body is currently mortal, that at the apex of the soul is a mind, an original intellect that is in fact who we are, that that original intellect is made to praise God in loving communion with him, and that that praise radiating downwards through the soul, animating the body, is meant to manifest as virtue in pursuit of purity of heart and the knowledge of true contemplation resisting all ignorance. That it is precisely the degree and the quality of the mind’s contemplative activity and the soul’s loving power that determines where and in what state the soul will be after death: hell or heaven. Abba Moses wants us to take all of these things seriously.

Because Abba Moses knows from deep experience deep in the deserts of Egypt that it’s all true.

And so I encourage you to take it seriously and in fact encourage myself to take it seriously. We could all do with taking these things more seriously.

Which is why, no doubt, you are listening to Life Sentences. It’s certainly why I’ve created Life Sentences.

With that, I will bring this episode of Life Sentences to a close. We are not finished with Abba Moses, certainly not with John Cassian. Next time, Abba Moses will continue his conversation with John Cassian. He will talk about contemplation in particular in greater detail. So that’s what the next episode holds in store.

Thank you very much for listening to this episode of Life Sentences. If you enjoyed it and if it has helped galvanise your soul in pursuit of virtue, then please consider taking out a paid subscription to the podcast. Without more paid subscriptions, I will not be able to continue Life Sentences.

Many thanks again to all of you who have taken out paid subscriptions. I really appreciate it.

Please share the podcast with your friends, with your family, with your enemies. Love your enemies, share Life Sentences with them!

And most of all, stay well.

Share this post