What follows is a complete transcript of this week’s podcast episode, which you can listen to in the Substack app or via your preferred podcast platform.

The podcast is designed to be listened to, so I encourage you to listen. But I’m also providing transcripts, as you may want to read along as you listen.

Welcome to Life Sentences, an exploration into the wisdom of the ancient Church Fathers presented by me, Thomas Small.

In this episode, Abba Moses tells us more about what contemplation actually is, explaining its different modes, and also teaching us where our thoughts come from and what we’re supposed to do with them.

In the last episode, we were working our way through John Cassian’s Conference No. 1. And when we left them, John Cassian and his beloved friend Germanus were listening attentively as Abba Moses told them all about the kingdom of God: about what it is, about how to arrive at it, and about how to avoid its opposite, the kingdom of hell.

You’ll remember that the kingdom of God is our ultimate end, and that to attain it we must remain focused on our proximate goal, purity of heart, which Abba Moses links with dispassionate love and theoria, contemplation.

Well, in this episode, Abba Moses is going to dive deeper into contemplation. He’s going to focus a bit more on the practical side of contemplation, or at least on the content of contemplation. When we contemplate God, what are we seeing? Noetically seeing, I mean? Invisibly seeing?

However, before we launch back into Abba Moses’s discourse, which will bring us to the end of Conference No. 1, let’s continue on our journey through Cassian’s life.

When we left off in the mid 380s AD, Cassian and Germanus, still young men, were finally arriving in Egypt. Both were burning to receive instruction in the contemplative mysteries from the great Desert Fathers.

Now, after arriving by boat they were greeted by Archebius, an obliging bishop who, though considering himself a failure in the monastic life, offered to take the two travellers along with him back to his episcopal see and to introduce them to some Desert Fathers en route, including their old friend, Pinufius. Do you remember him? He’s the abbot who fled his monastery seeking anonymity in Bethlehem and who’d whetted Cassian’s appetite for real contemplation before being tracked down by his relentless disciples and dragged back to Egypt.

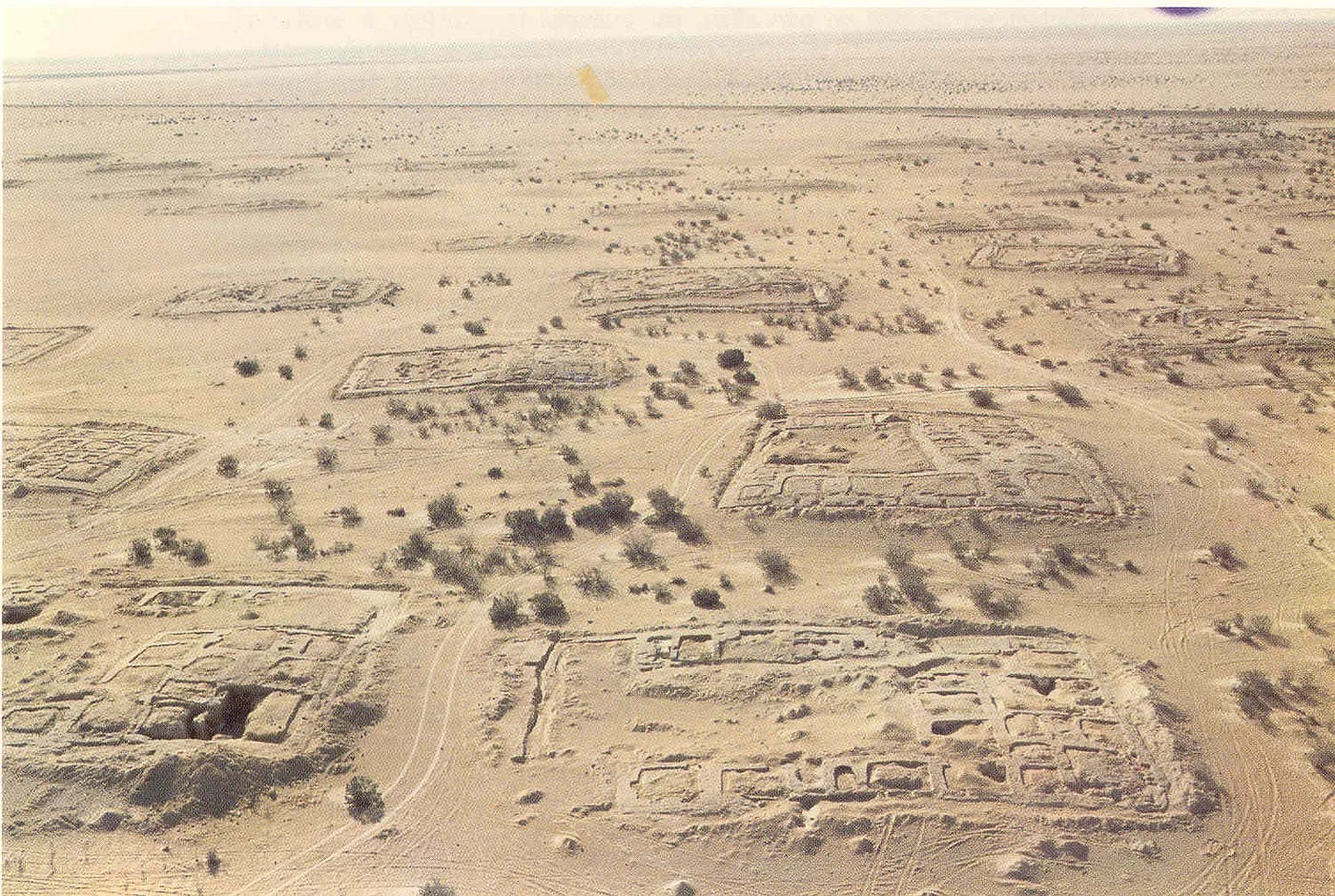

When Cassian and Germanus were reacquainted with Pinufius, they were still in the Nile Delta, not yet in the desert proper. And yet Cassian describes an eerily empty landscape populated only by monks. The sea, he says, had been slowly encroaching on the land, devouring the coastal towns, forcing all but the monks to flee. His description is unsettling, otherworldly. You feel this world passing away.

Another father they met on their way, the elder Piumun, was really worked up about gyrovagues, as he called them, itinerant monks who were always on the move and never settled down anywhere. Cassian and Germanus may have felt the sting of this rebuke, since before long they arrived in the monastic enclave of Scetis, in the actual desert, where they stayed put for several years. It was in Scetis that they got to know Abba Moses.

The chief monk of Scetis, to whom everyone there looked for spiritual guidance, was Paphnutius. Paphnutius loved withdrawing deep into the desert. So much so that his followers gave him an affectionate nickname, the Antelope. A real character, Pafnutius was humble but also tough, quick to call out error in his charges. He was also an Origenist—that is, a follower of Origen.

Origen lived in the third century, dying roughly 150 years before John Cassian arrived in Egypt. Origen was not a desert dweller, far from it. Origen was an Alexandrian by birth, upbringing, and education, well-versed in philosophy and rhetoric, but also a lifelong Christian. His father was a professor of pagan literature and so also walked the line between pagan culture and Christian wisdom—and died a Christian martyr during the persecutions of the emperor Septimius Severus. When he was still a boy, Origen watched his father be martyred, and always longed to follow in his footsteps.

But instead, he grew up to become head of Alexandria’s catechetical school where he taught the newish Christian philosophy, emphasising asceticism and prayer and the art of biblical exegesis.

Origen believed that beneath the literal sense of scripture lay a multi-layered spiritual sense, which the Holy Spirit revealed to the one who purified his mind. Therefore Origen felt authorised to draw on Scripture to speculate about metaphysical, cosmological, and eschatological subjects—subjects on which, in his view, the Apostles of Christ had not laid down any authoritative teaching.

Origen’s speculations were always controversial. Even in his own time, his writings created a stir. And yet he always had devotees, men and women both, who turned to his vast number of written works for illumination, consolation, and practical advice. Some of these devotees remain illustrious figures in the memory of the Church, as we’ll see down the line.

And yet this is not the case for Origen himself. Hundreds of years after his death, in AD 553, several speculative teachings then circulating under Origen’s name would be condemned at the Fifth Ecumenical Council, as was Origen himself—or so it is believed, scholars debate this. But certainly the church turned against Origen. His writings were destroyed, neglected, lost—or sometimes read only in secret.

Anyway, this is not an episode about Origen of Alexandria. This is an episode about John Cassian: the great expositor of the Christian contemplative tradition; the man whose encyclopaedic account of monastic spirituality, the Conferences, profoundly influenced monks and nuns east and west for centuries, indeed down to the present day; the man who, for the 10 or 15 years he lived in Egypt, attached himself to a group of monks he admired immensely, a group of monks who were all Origenists—as was John Cassian himself.

In fact, as I mentioned last time, John Cassian’s teacher, his spiritual father during his time in Scetis, none other than Evagrius Ponticus: a remarkable man, a daring speculative thinker, and a master of contemplative prayer. Perhaps you remember last time, Abba Moses mentioned what he called the ‘original intellects’, which was a trace, I said, of Evagrius, a taste of his thinking.

Well, John Cassian’s writings are permeated by Evagrius’s thinking. And yet, Evagrius himself is absent. His name was arguably the most well known of all the names from the Egyptian desert, and yet Cassian doesn’t mention it, not even once.

Something happened between Cassian’s arrival in Scetis in the late 380s and his taking up the pen to write the Conferences thirty-five years later. Something which led him to obscure and even deny that he’d ever had anything to do with Evagrius Ponticus.

What that thing was, we’ll discover next time.

For now, back to Abba Moses and the final part of John Cassian’s Conference No. 1.

Right, as I said at the outset, in this last part of Conference No. 1, Abba Moses is going to start out by talking a little bit more about theoria, contemplation.

Recall that, along with purity of heart, contemplation is, according to Abba Moses, ‘To feed on the beauty and wisdom of God alone.’ Abba Moses also said, ‘This must be our principal effort, this the unwavering determination of the heart that must be continually sought, that the mind always cleaves to divine things and to God.’

The mind always cleaves to divine things and to God. That, he says, must be our principal effort. But what is it? This is what he’s going to tell us now.

Now just to remind you, I have edited the text somewhat. I have shortened it in places, cut out some superfluous bits, in order to streamline Abba Moses’ presentation. But I hope it will all make sense.

Okay, so right away Abba Moses says:

‘The contemplation of God can be arrived at in various ways. For God is not known only in wonder at his incomprehensible substance, which is still hidden in the hope of the promise, but he is also made known through the greatness of his creatures, or by considering his justice, or by the help of his daily providence.’

So in that quote before, Abba Moses defined contemplation as ‘the mind always cleaving to God’, he said, ‘and to divine things’. And here in this opening bit, he is restating that again.

So first of all, he says, God is not known only in wonder at his incomprehensible substance. So that’s contemplating God himself. But notice Abba Moses’ really important language here. He describes this first type of contemplation, the contemplation of God, as ‘knowing God in wonder at his incomprehensible substance’. You know something that is incomprehensible in wonder.

It’s a kind of weird way to describe knowing. How can you know something that’s incomprehensible? And surely, don’t you wonder at something that you don’t know?

What Abba Moses is saying here is, like, a bedrock teaching of Christian spirituality, Christian mysticism, Christian contemplative prayer: that God is unknowable in his substance, or essence. God’s essence is not knowable, not in the way that we know created things. So though Abba Moses has said it’s a kind of knowledge, a knowledge ‘in wonder at God’s incomprehensible substance’, it’s not anything like the kind of knowledge we ever experience about created things.

Why is that? Why is God in his essence incomprehensible, ineffable, unknowable?

The first thing to say is that it is not because God can be known but refuses to reveal himself. Not at all. God has revealed himself: in his creation, in the Scriptures, and most especially in the Incarnation. And yet God’s essence remains not only unknown but unknowable. That’s what Abba Moses is saying.

Why? Well, anything that can be known, that can be comprehended or grasped by the intellect, is in some sense at least a thing, a being. If your mind can comprehend something, that thing exists. And the reverse is equally true. If something exists, then it can be comprehended by the mind. There is a certain convertibility between being and knowing. To be is to be intelligible. To be intelligible is to possess being.

And now, this applies as much to a grain of sand as it does to the whole universe. Both the very small and the very large possess being and are therefore knowable by the mind. You know, even something imaginary—like say Richard Dawkins’s notorious Flying Spaghetti Monster—even something imaginary like that exists as an imaginary concept. It therefore possesses being in that imaginary mode and can be known by the mind.

But God is not a being. He does not possess being like you and I do. God is the source of being. He is therefore beyond being as its source.

Because God is beyond being, he is also beyond knowing. Since you can only know that which possesses being, the One who does not possess being, because he is the source of the being that beings possess, that One cannot be known.

This is why we don’t say that God is merely unknown. We say that he is unknowable, specifically unknowable in his essence or substance.

Now, this way of thinking can be hard to wrap your mind around, but that’s okay. When we turn our minds in contemplation toward the One God, we quite literally can’t wrap our minds around him. And so it would even be wrong to try. We do not ponder God as we ponder a philosophical or, even less, a mathematical conundrum, seeking logical clarity and tidy definitions. Instead, before God’s awesome ineffability, our mind falls silent. Instead of grasping him intellectually, we turn to him in profound wonder, praise, thanksgiving, and worship.

So this way of encountering God in contemplation, which the tradition actually sometimes calls unknowing, is the proper way of contemplating him.

And yet, as Abba Moses says, it’s not the only way. For he says God is not only known in wonder at his incomprehensible substance. And in fact also he said that that substance is ‘still hidden in the hope of the promise’. Which is a tidy reminder that whatever we contemplate of God now, in this life, in these bodies of flesh, is nothing compared to what we will contemplate of him in the next life: after through purgation our minds, our souls, our hearts have been purified and our bodies are resurrected, restored, made spiritual in glory.

Anyway, that’s on the other side of the grave. On this side of the grave, in addition to contemplating God in wonder at his incomprehensible substance, he is also made known to us, Abba Moses says, through ‘the greatness of his creatures’, or by ‘considering his justice’, or by ‘the help of his daily providence’. These are among the divine things that the mind is also meant to cleave always to—the divine not in its essence, which is incomprehensible, but in its energies, its operations, its activities, whereby God manifests himself in creatures and in the way he governs and orders reality, inclining it always towards the final good.

And of this side of contemplation, the contemplation of the divine things, Abba Moses says:

‘When indeed we examine with the purest mind the things he has done with his saints through each generation; when we marvel at his power by which he governs, moderates, and rules the universe; when we are struck with awe at the immensity of his knowledge and the eye before which the secrets of hearts cannot remain hidden; with trembling hearts when we reflect on the sand of the sea and the number of its waves measured and known to him; when we consider the drops of rain, the days and hours of the ages, and all past and future things, standing in wonder at his knowledge; when we contemplate his ineffable mercy, by which he bears with tireless patience the countless sins that are committed under his gaze at every moment; when we reflect on the call by which, without any preceding merits, he has admitted us by the grace of his mercy; and finally when we regard with a certain excess of admiration the many opportunities for salvation he grants to those he adopts: that he ordained us to be born in such a way that from our very infancy the grace and knowledge of his law might be given to us; and that when he overcomes the adversary within us, he rewards us with eternal happiness and perpetual blessings for nothing more than the consent of a good will; and when at last he undertook the dispensation of his Incarnation for our salvation and spread the wondrous mysteries of his works among all the nations.’

Okay really, a cascading list of contemplations of the divine there. And the first thing to point out is, at the beginning of that list, he says that these are all things, these divine things that we’re contemplating, these are all things that we examine with the purest mind. The purest mind. And it’s tempting to suggest there that Abba Moses thinks that contemplating God in his energies, contemplating God as God is manifest in the created world, is perhaps the highest contemplation of all. Or at least, the contemplation requiring the greatest degree of purification.

Because a mind that is not pure attaches to created things: whether sense-perceptible created things ,or mental created things like ideas, concepts, what have you. If the mind is not pure, it cannot contemplate the God that is present in those created things, making them what they are, manifesting himself through the created things. Instead, an impure mind attaches to those things and cannot see God. For that reason, to contemplate the divine things as they are manifest in the created order requires the purest mind.

And the first thing he lists there, which we would contemplate, is ‘the things that God has done with his saints through each generation’. And you wonder, why is that first?

I would suggest that, as the image of God, the human being, when he is manifesting God, is manifesting God in the most unadulterated, the most perfect way. So if you really want to contemplate God in the created order, you will contemplate him in a perfected human being, in a saint. It is in fact because the saints who now dwell in heaven have been perfected by God and are so full of God’s grace that we can turn to them and beg their intercession. It’s also why we read the lives of the saints: we literally recall to mind their virtues. In so doing, we’re actually contemplating God, whose activity it is that empowers the saint, because it is God’s activity flowing through the saint that makes them saintly, because he is the source of all holiness, of all sanctity.

It’s important to bear that in mind because, though the cult of the saints is a big part of Christianity, when we venerate the saints, we’re not really venerating anything other than God, because in the saints we contemplate God himself in his energies, in his activities. The goodness, the holiness, the beauty, the purity of the saints, is in fact the goodness of God, the purity of God, the holiness of God. So, contemplating the saints, we contemplate God.

And then the second thing in this list of contemplations is when Abba Moses says we ‘marvel at God’s power by which he governs, moderates, and rules the universe.’

Now any sceptics among my listeners might just roll their eyes at this, but it kind of goes without saying: that the marvels which modern science has uncovered, revealed about the nature of the cosmos: its order, the laws by which it is governed, laws that are remarkably ordered, mathematical, structured, beautiful indeed; it goes without saying that these marvels, which modern science has helped us to contemplate, are in fact all manifestations of God’s power.

And even before the Scientific Revolution, you know, people looking up at the sky could tell the remarkable orderedness of everything. Looking down at the earth, they could see the regularity, the cyclical regularity, of the seasons, of the agricultural cycles, of the tides coming in, coming out, in sync with the moon waxing and waning. And you don’t have to isolate these factors in a laboratory or be able to describe their geometric or mathematical dimensions to know that everything is governed by order. And contemplating that is to contemplate God’s power, Abba Moses says.

And then he says we also contemplate ‘the immensity of God’s knowledge’ and ‘the eye before which the secrets of hearts cannot remain hidden’. And included within God’s knowledge, he says, is the sand of the sea, the number of its waves, the drops of rain, the days and hours of the ages, all past, all future things: all that is knowable, Abba Moses is saying, anything that can be known—i.e. anything that is, anything that possesses being—is known by God.

And in fact, when we know something, we are really knowing with God’s knowledge. The knowing of the thing is an energy and activity of God that the human mind can participate in and does participate in when it knows something.

But if, as I said at the beginning of this episode, there’s a kind of convertibility between being and knowing, then God, who is the source of all being, is in a way the being of things that are; and therefore, as the source of all knowing, is in a way the knowledge of everything. Not just objects but also times, seasons, events; and not just present but past and future. Everything that is that possesses being possesses that being by being known by God. And if we have the purest mind, we can contemplate God in that way as well.

So all of that—the things he has done with his saints, the power by which he governs, and the immensity of his knowledge—all of that is to contemplate ‘the greatness of God’s creatures’, that first of the three categories of divine things that Abba Moses listed at the start.

The second of which was God’s justice. And it’s interesting in that long list of contemplations, Abba Moses links the contemplation of God’s justice with the contemplation of God’s ineffable mercy—the mercy by which, he says, God ‘bears with tireless patience the countless sins that are committed under his gaze at every moment’.

It’s an absolutely vital part of the Desert Fathers’ teaching that God’s justice is manifest in his mercy, in his patience, in his forgiveness. The God of the Desert Fathers is not a God of vengeful wrath, not in the end. For the one starting out on the spiritual path, whose conscience still needs refinement, it is perhaps the case that God is a God of wrath for that beginner. But in time, after the beginner has become an elder and his mind has been purified, the contemplation of God’s justice is the contemplation of God’s mercy, of his patience, and of his limitless forgiveness.

And also, it’s a contemplation of God’s justice, Abba Moses says, when we reflect on the fact that everything we have, we have only by the grace of God’s mercy. We had no preceding merits, Abba Moses says. There was nothing we’d done, as it were, before our existence to be granted the wondrous gift of being. And not just the gift of being, but, as he goes on to say, the opportunities for salvation that God grants to us. So God’s justice, which is also his mercy, hasn’t just called us into being, but is guiding us towards salvation.

And this is where the third of those three categories of divine things that we contemplate comes up. First, the greatness of his creatures, then God’s justice, and three: his providence.

Abba Moses is clear that everything is shot through with God’s providence. God, he says, has ordained us to be born. Ordained us to be born in such a way that from our infancy we are given grace and knowledge of the moral law. It is by God’s providence that God himself, Abba Moses says, ‘overcomes the adversary within us’ but then gives us the rewards for his own victory, demanding from us, Abba Moses says, nothing more than the consent of a goodwill—nothing other than that we simply allow God to do this work inside of us, because it is God’s providence that guides and leads all things in the end.

And it is divine providence informed by God’s mercy that ultimately manifests itself in the creation. Which is why the last in that list of contemplations is the dispensation of Christ’s Incarnation for our salvation and the spread of the wondrous mysteries to every corner of the earth—the wondrous mysteries which invite us to participate in that providential outflowing of merciful transformative grace, leading us all and indeed the entire creation into the eternity of the kingdom.

So all of this is a sort of idea of what Abba Moses means when he talks about contemplating the divine things.

And then he goes on:

‘But there are also countless other such contemplations which arise in our perceptions according to our quality of life and purity of heart, by which in clear glimpses God is either seen or grasped. However, no one will be able to retain these continually in whom fleshly passions still live because the Lord says, ‘You cannot see my face, for no man shall see me and live’—that is, live in this world and in earthly passions.’

So just in case you think all that contemplating comes for free, Abba Moses brings us back down to earth and reminds us that true contemplation follows upon purity of heart. So we will only glimpse these divine things to the degree that we have achieved purity of heart by overcoming fleshly passions. It is passions of the flesh, when the mind is attached to objects of sense perception, overcome by desire for possession of those objects and anger at people who try to come between you and those objects; in that state, the heart is not pure and you cannot contemplate God, neither in wonder at his incomprehensible substance, nor in the divine things that surround him and which permeate the creation, though we cannot see it.

It’s interesting that Abba Moses quotes the line from Exodus, ‘You cannot see my face, for no man shall see me and live,’ and then interprets that verse in quite an unusual way. Normally that verse is one of those places in the Bible where God is portrayed as a figure of great power, wrath, terror. You know, he will burn up the impure. If the impure come to him, they’ll be consumed with divine fire. Abba Moses has taken that conception and turned it on its head, in a way. Because he says that by ‘live’ there, the Bible indicates living in this world and in earthly passions. So it’s not that if you see God you will die. Instead, Abba Moses is saying, that if your life in this world is one of fleshly passion then you cannot see God.

And that is linked back to purity of heart. Because in the Beatitudes, remember, Christ said, ‘Blessed are the pure in heart for they shall see God.’ So that passage from Exodus, which at the literal level is portraying a God of fearsome wrath, Abba Moses is suggesting that at the spiritual level, underneath the literal level, it’s the other way around: God is a God of mercy, and that if we follow the path that he laid down for us when he lived on this earth, taking up our cross, following him on the road of laying down the flesh, and in self-sacrifice loving other people, then the vision of God will be ours.

So that’s Abba Moses on contemplation, trying to inspire us to pursue purity of heart by following the commandments of Christ so that we might see God in all of his extraordinary glory.

And after this quick break, when we come back Germanus is going to shift the conversation away from the heights of contemplation and down to the everyday reality of being distracted by thoughts.

We’ll be right back.

We are back! Germanus, having just heard Abba Moses describe contemplation in both of its primary modes—the contemplation of God in wonder at his incomprehensible substance, and the contemplation of the divine things around God that permeate the creation—having heard all of that, Germanus then asks:

‘What then is the reason that against our will, and even without our knowledge, superfluous thoughts subtly and secretly creep in, so that it is not only difficult to drive them away, but even to understand and detect them? Can the mind ever be found free from these and never be assaulted by such illusions?’

That’s a great question, Germanus. Why is it with all these contemplations on offer, instead we go about our lives bombarded constantly with superfluous thoughts? Our mind wanders from this thing to that, we focus on all sorts of ridiculous and unnecessary things, when all around us all the time God’s glory is radiant, we’re just not seeing it.

Why is this and how can we be free of it?

Abba Moses answers:

‘It is impossible for the mind not to be disturbed by thoughts.’

Right. Okay, impossible. It’s impossible for the mind not to be disturbed by thoughts.

I suppose that’s an encouragement. As we live our lives bombarded by these superfluous thoughts, even wicked thoughts, it’s something at least to know that remaining completely undisturbed by such thoughts is impossible.

So yes, it is impossible for the mind not to be disturbed by thoughts, but then Abba Moses continues:

‘But to accept or reject them is possible for anyone who applies effort.’

Right, from encouragement to, well, if not discouragement, then to a clear statement of the challenge.

So we cannot prevent thoughts from disturbing us, but we can reject them. We can keep ourselves from being overwhelmed by them, if we apply effort, he says.

And he goes on:

‘It is true that their origin does not entirely depend on us, but it is equally true that their rejection or acceptance does depend on us. So even though we have said it is impossible for the mind not to be attacked by thoughts, it does not follow that we should attribute everything either to the invasion or to the spirits who attempt to implant them in us. Otherwise man would have no free will, nor would his efforts to correct himself endure within him.’

So Abba Moses would certainly not agree with some modern voices who say that our thoughts or our entire experience of our subjective selves is completely, as it were, outside of our control; those voices that say that free will is an illusion. The mind—or really the brain, these people tend to think–is automatically operating according to its own powers, programming—generates thoughts, dreams, wishes, purposes, desires—generates everything that we think; and that we ourselves are really just being subjected to that, if there even is a self.

Abba Moses would reject that view. He makes it clear here that we do have free will, and for that reason, though there’s nothing we can do to prevent ourselves from being bombarded by distracting thoughts, we are in control of what we accept or reject. We do have free will. We can’t blame everything on the invasive thoughts as if we are simply passively subject to them, nor can we blame only the demons, he says, who at least in part are attempting to implant these thoughts in us. We are in control of what we accept or reject. We do have free will.

And Abba Moses brings a moral perspective to bear on this question. Because he said if we didn’t have free will then the efforts that we expend to correct ourselves—to grow in conscience, to grow in spiritual strength, to cultivate and acquire purity of heart—those efforts would not endure, he says. If our free will is simply an illusion and all our efforts at virtue are just an illusion, then we could never have confidence that, as we grow spiritually, that spiritual growth is real and won’t just be overturned willy-nilly as and when our brains or the demons decide.

But no, we have free will and as we grow in virtue the freedom of our will grows, our freedom grows. We become more and more capable of remaining free from the invasion of these thoughts. Spiritual growth is real because we have free will and because we can reject evil thoughts and accept good thoughts. That is up to us, as Abba Moses goes on to reiterate.

He says:

‘But it is, I say, largely up to us whether the nature of our thoughts is improved and whether either holy and spiritual ones or earthly and carnal ones are established in our heart.’

Okay, a very straightforward binary there. There are two basic categories of thought: holy and spiritual on the one hand, earthly and carnal on the other hand. Within those two categories there might be a degree of variety, but those are the two basic categories of thought: holy or earthly; spiritual or carnal.

And he says it is largely up to us which of those two kinds of thought are established in our heart. Not up to us which kind of thoughts distract us, but up to us which of the two kinds of thought are established in our heart. And depending on which kind of thought we establish in our heart, the heart itself will generate thoughts that are either holy and spiritual or earthly and carnal. So the nature of our thoughts, the thoughts that our heart generates, can be improved based on which kind of thought we allow to be established in our heart.

The heart really is like a field and the thoughts that we allow to be established in our heart are like seeds we plant in the field. If we plant the seed of holy thoughts in our heart, our heart will produce holy fruits. If we plant the seed of carnal thoughts into our hearts, our hearts will produce carnal fruits. And so Abba Moses says we are largely in control of what kind of thoughts well up from within our own hearts because we are in control of what kind of thoughts we allow to be planted in our hearts in the first place.

And so he goes on to say:

‘For this reason, frequent reading and constant meditation on the scriptures are prescribed, so that they may offer us the occasion for spiritual remembrance. For this reason, the frequent chanting of psalms is recommended, so that continual compunction may be ministered to us. For this reason, the diligence of fasts, vigils, and prayers is encouraged so that the mind, thinned down, instead of savouring earthly things may contemplate heavenly things. But when negligence creeps in and these practices are abandoned, it is inevitable that the mind, hardened by the filth of vices, soon inclines to the carnal part and collapses.’

So here Abba Moses is listing the sorts of holy and spiritual thoughts that we can implant in our hearts by reading and meditating on scripture, by chanting psalms, by practising vigil, by praying, by fasting. These are, once again, all of those indispensable means whereby we move towards that proximate goal, purity of heart—i.e. a heart in which only good thoughts have been sown, and which only produces holy thoughts, which is the contemplation of God.

You see how this works? Like jazz, really, Abba Moses is simply riffing on the same theme: purity of heart and contemplation of God.

And just to point out that when he mentions fasting there, he specifies that it’s so that the mind might be thinned down. Again, fasting is so that we detach our minds from objects of sense perception. It’s not essentially about the body, about being thin, about being weak. It’s essentially about the mind, preventing the mind’s passionate attachment to earthly things so that it can contemplate heavenly things. So that’s why we read the scriptures, that’s why we pray, and so on.

And contrary-wise, if we don’t—if we succumb to negligence and we abandon all those indispensable means—then he says it is inevitable that our minds will be hardened by filth and, inclining to the carnal part, collapse. What an image of spiritual death, really. Blindness, the end result of sloth.

Abba Moses goes on:

‘The activity of the heart is not inappropriately compared to the turning of millstones, which the rushing flow of water propels with a rotating force. These cannot cease from their work, being driven by the force of the waters, but it is within the power of the one who oversees them to decide whether to grind wheat or barley or darnel. For it is beyond doubt that what will be ground is whatever is placed into the mill by the one who has been entrusted with the care of that work.’

I think that metaphor is pretty clear.

Darnel, by the way, is a weed that resembles wheat but is toxic. So if you eat darnel you’ll become dizzy and nauseous. And in the Bible this word is often translated ‘tares’ or ‘weeds, but it is more specific. It is a weed that looks like wheat but is poisonous. As we’ll see later on in this episode, Abba Moses is going to specify evil thoughts as masquerading as good thoughts, like darnel masquerades as wheat.

But yes, this metaphor of the miller choosing what kind of wheat he grinds in the millstone: the millstone, which moves and moves and moves, because the water wheel is always turning, because the water is always turning it. The water, which Abba Moses now goes on to say, symbolises the constant bombardment of thoughts which the mind cannot help but be subject to.

He says:

‘Thus the mind too, driven by the torrents of temptations that press upon it from all sides during the course of the present life, cannot be free from the turmoil of thoughts. However, what kinds of thoughts it ought either to cast away or to acquire for itself, the diligence and effort of its own careful industry will determine. For if, as we have said, we continually return to the meditation of the Holy Scriptures and elevate our memory to the recollection of spiritual matters, the desire for perfection, and the hope of future blessedness, then it is necessary that the thoughts arising from this will cause the mind to dwell on those spiritual things that we have meditated upon. But if, overcome by laziness or negligence, we are preoccupied with vice and idle conversation, or if we are entangled in worldly cares and superfluous anxieties, then consequently this will produce a kind of weed-like growth that inflicts harm upon the heart.’

Now, I don’t know if you’re like me, but if you are like me, you may find that you spend too much time on the Interneτ. Τoo much time on Twitter, or X as it’s called now, or whatever your favourite social media platform is. Τoo much time reading the news, too much time watching the news. Τoo much time watching YouTube clips. Ιn essence, being preoccupied with vice and idle conversation, entangled in worldly cares and superfluous anxieties. All of this Abba Moses would consider to be gross laziness and negligence, and he says it produces weed-like growth in the heart that inflicts harm upon it.

So pray for me, because I do spend too much time on the Ιnternet. Let’s all pray for each other. We must stop allowing ourselves not just to be bombarded by such ‘content’, as it’s called, but by giving it our attention and meditating upon it as we do, allowing it to take root in our hearts.

Now, having talked about the two kinds of thought, holy and carnal; having talked about our responsibility to choose only the holy thoughts and reject the carnal ones; Abba Moses now talks about the three sources of our thoughts.

He says:

‘This we must be aware of above all, that there are three sources of our thoughts: God, the devil, and ourselves.

‘They come from God when in his kindness he visits us in the illumination of the Holy Spirit and leads us up to a higher state; or, when we have been worsted through our failure to profit by grace or by our idleness, he corrects us with his saving compunction; or again, when he opens the heavenly mysteries to us and turns our intention and will toward better actions.’

Right, there are three sources of our thoughts: God, the devil, and ourselves. Extremely clear. And he first talks about the thoughts that come from God.

However, notice that the thoughts here aren’t really like the everyday kind of thoughts that we usually have or that we’re used to. It’s not that God is, like, speaking to us in our heads. He’s not putting a voice in our heads. These three kinds of thought from God are nothing like that.

At least they don’t seem so to me. ‘When God in his kindness visits us in the illumination of the Holy Spirit and leads us up to a higher state.’ If the word ‘thought’ is employed to describe that, then we’re talking about thought at a very different level, a much higher level, I would imagine the raising up of our consciousness to a level beyond mere thinking. This is the illumination of the Holy Spirit leading us up to a higher state.

Or even when we’re quite low down and he says that we’ve been worsted through our failure to profit by grace or by our idleness, but then we feel compunction. Again, this is not so much a thought or a thinking, it’s like a transformation of our inner selves towards penitence, towards compunction. This is a thought, he says, from God.

And finally, the third so-called thought from God is when God ‘opens the heavenly mysteries to us and turns our intention and will toward better actions’. So again, not a thought in the sense of thinking, not words in the mind, but a divinely affected transformation of our inner selves, turning our intention and our will towards the better.

These are the three sorts of thoughts that God gives us: spiritual illumination, compunction, and the reformation of our will.

But what about the devil? What kind of thoughts come from the devil? Abba Moses tells us.

He says:

‘But a sequence of thoughts arises from the devil when he tries to subvert us, both by the pleasure of vices, and by hidden snares, deceitfully presenting evils as goods with the utmost cunning, and disguising himself to us as an angel of light.’

So the first thing to point out there, interestingly, is that when Abba Moses talked about the thoughts that come from God, he said simply that: thoughts that come from God. And he described them, as I pointed out, as like actions of God on the soul, transforming it towards illumination, towards compunction, towards repentance. But here, talking about the devil, Abba Moses says that he causes a sequence of thoughts to arise.

And so now we’re turning more towards thinking as we normally understand it, as a sequence of thoughts. So unlike the divine thoughts, which come to us, really, as one divine action, transforming us in some way, the devil’s thoughts appear as a sequence in our minds. As an attempt by the devil, Abba Moses says, to subvert us.

In a way, the devil tries to have a conversation with us. He’s the one whispering in our ear, holding out, Abba Moses says, the pleasure of vices before us; or even worse, hidden snares, where he deceitfully presents evils as goods. And if we allow him enough hold over us, and have allowed him to puff us up in self-aggrandisement, self-esteem, and pride, he’ll even appear to us as an angel of light, mimicking the spiritual illumination that is the first of the thoughts of God.

And in fact, it’s all there in that word ‘subvert’. The devil is a subversive. If the thought of God turns our intention and will towards better actions, the sequence of thoughts from the devil tries to turn our intention towards pleasure. If a thought from God reveals our sin and generates compunction in us, a sequence of thoughts from the devil tricks us, making us think the evil in us is good, so that we will remain in our sin. And if, at the highest, a thought from God is God himself visiting us in the illumination of the Holy Spirit, then at its worst, a sequence of thoughts from the devil is when he comes and disguises himself to us as an angel of light. You see the subversion there, the inversion, the mirror image: God and the devil.

But what about the thoughts that come from ourselves?

Abba Moses says:

‘But thoughts arise from us when we naturally recall the things we are doing, have done, or have heard.’

So there we clearly have the kind of thinking that we most often experience: everyday, ‘natural’ (as Abba Moses says) thinking, where we simply call to mind things that we’ve experienced, things that we’ve heard or learned, or focus our thoughts on what we are doing right now. This is natural. These thoughts come from us.

And one thing to stress is that we do have our own natural thoughts. Sometimes people pursuing a spiritual life can forget this and can begin to think that the thoughts in their heads are either from God or from the devil only.

You can imagine what that kind of mistake might give rise to. On the one hand, spiritual pride potentially, where your own thoughts are mistaken for God’s thoughts. I think that’s extremely common. But on the other hand, and in a way even worse, when you begin to worry that all of your thoughts are from the devil. Α kind of spiritual paranoia can take over where you think you naturally wouldn’t have thoughts, and if you have thoughts that aren’t divine thoughts, then they’re all from the devil. This is paranoid. You begin to see the devil in every thought.

Well, Abba Moses says that’s not the case. Thoughts arise from us naturally, he says. Everyday thoughts, everyday memories, everyday knowledge. These thoughts come from us.

So having specified three sources of our thoughts—God, the devil, and ourselves—Abba Moses goes on:

‘Now we should be careful to scrutinise these three types of thought and discriminate wisely between all the thoughts that emerge in our hearts, first tracing their origins, causes, and authors so that we can know what value to lay on them depending on the authority of the one who suggests them to us. Thus we shall be, as our Lord commands, skilled money changers.’

Okay, so that’s pretty clear. He’s saying that when we remain attentive to ourselves, we remain collected, focusing our attention on our hearts, watching the thoughts that rise in our hearts, that emerge, as he says, in our hearts, scrutinising them, and first and foremost, determining their origin, determining which of those three sources of thoughts, God, ourselves, or the devil, they come from.

Now I dare say the vast majority of the thoughts that you scrutinise in that way will be thoughts that are naturally generated by yourself. But even so you want to prevent those thoughts from being established in your heart. We don’t want to be sowing everyday thoughts into our hearts. We only want to be sowing holy thoughts into our hearts.

So yes, when thoughts emerge in our hearts we must notice them and first trace their origins, ‘So that,’ Abba Moses says, ‘we will be skilled money changers, as our Lord commands.’

That’s a really fascinating passage. Because if you know your Gospel you’ll know that nowhere in the Gospel does Christ command us to be skilled money changers. There’s the story in the Gospel where he overturns the tables of the money changers in the temple, so there’s a reference to money changers in the Gospel, but nowhere does he command that we should be skilled money changers.

And interestingly, this is an example, one of many scattered through the writings of the early Church Fathers, of what are known as the agrapha, the unwritten sayings of the Lord that appear in patristic writings. This one is specifically known as Logion 43, which shows you how many of these agrapha sayings there are. So scholars, reading through the Church Fathers, have found places where a given Father will quote the Lord, but the quote will not be in the Gospel. Almost as if, in addition to the written Gospels, there were unwritten oral sayings of Christ that circulated amongst early disciples and were passed down by word of mouth.

Christians today are largely unaware of this material, but it’s there in the Church Fathers, and it’s important. They took it seriously. They considered the agrapha sayings to be as meaningful as powerful and as true as anything in the Gospels, like here when Abba Moses says that the Lord commanded us to be skilled money changers.

And he says that Christ meant by that this activity of discriminating between our thoughts. And though there isn’t time to read the whole quite long passage, where Abba Moses describes in some detail the different kinds of coin that a money changer scrutinises, linking each kind of coin to a different kind of thought; and in fact it becomes very complicated, and the kinds of thoughts that Abba Moses is interested in are quite theological or scriptural, questions of orthodoxy or heresy, questions of doctrine, etc.; so though there’s no time for me to read through that whole passage, what the passage reveals is that men like Abba Moses, men like the Desert Fathers, and indeed any of us who, with effort, discipline, and attention, pursue purity of heart and contemplation, must prioritise this exercise of discriminating between our thoughts, where they come from, and discerning which are holy and good, which are evil and malicious, and which are vain and idle.

And we must be skilled money changers because, as I said before, the devil especially is trying to pass off evil thoughts for good. As Abba Moses says, like a counterfeiter who’s trying to trick a money changer that a brass coin that’s just been covered in gold paint is a gold coin. This is, Abba Moses says, how the devil works. He’ll try to give us various kinds of counterfeit coins; or he’ll try to give us a gold coin but stamped not with the face of the true king but the face of a usurper, he says, so not a coin that is of legal tender; or a coin, he says, that is only partly gold, or is made of a fool’s gold, or has been clipped in some way, so the weight is less than it should be; All of these Abba Moses uses as metaphors for different kinds of devilish thought, which we must be on the guard against, scrutinising the thoughts that arise in our hearts carefully, only allowing those which are holy and pure to be established there.

As Abba Moses finishes:

‘We must be careful to scrutinise every corner of our hearts and examine diligently the tracks left by everyone who enters there, in case some beastly thought, some lion or dragon has passed through and left its nasty footprints behind, which may provide them access through our own negligent thoughts into other areas of our inner hearts. Every hour and every minute we should plough the field of our hearts with the Gospel plough–that is to say, the recollection of the Lord’s Cross—so that we may be able to root out and eliminate the nests of vile beasts and the lurking places of venomous worms.’

And that’s where our presentation of Abba Moses’ conversation with John Cassian and Germanus ends, on that final restatement of the ultimate theme: we must pursue, as our proximate goal, purity of heart.

This means to scrutinise, he says, every corner of our hearts to see what thoughts we’ve let in by accident, and not then to be negligent, but to remain attentive: to root out the monsters, the lions, the dragons who have entered in; to find them before they penetrate deeply, he says, into the inner heart; so that we can expel them before they get there.

And we do this, he says, by every minute ploughing the field of our hearts with the recollection of the Lord’s Cross: the Way of the Cross, the commandments of Christ, the indispensable means by which we pursue that purity of heart, which will give rise increasingly to the contemplation of God both in wonder at his incomprehensible substance and in praise at the glory of his manifestation in creation.

That is our proximate goal: purity of heart, giving rise to that contemplation and the dispassionate love with which we will walk the Way of the Cross and, in time, win the kingdom of God.

So we will say goodbye to Abba Moses, but we are not saying goodbye to John Cassian. We will be staying with Cassian and Germanus as they move on to other Desert Fathers, learning what they have to teach about the spiritual life.

And, after all, we still have to find out what happened in the desert that meant, many decades later, when John Cassian sat down to write the Conference, he made no mention whatsoever of his beloved spiritual father, Evagrius Ponticus.

So yes, we will not be leaving John Cassian just yet.

Thank you very much for listening to this episode of Life Sentences. As ever, I hope you enjoyed it. I hope you got some profit from it.

If you did enjoy it, please do consider taking out a paid subscription to the Substack. It truly is a lot of work to put these episodes together, as indeed it’s a lot of work to write the written posts which I post every other week. It’s a lot of work. I appreciate the support. I really do.

And with that I’ll say, until next time and stay well.

Share this post